Women

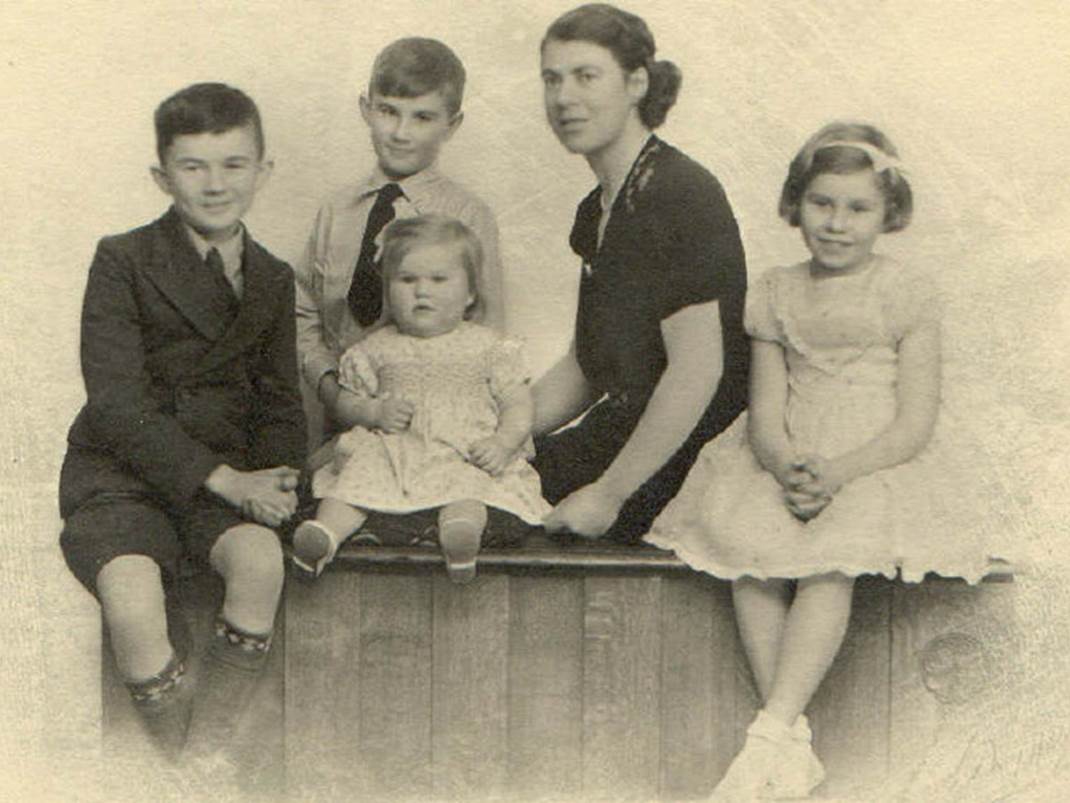

The sister Farndales of Tidkinhow

with Barker children - Willie B, Dorothy F, Mary F, Mary B, Kate F, Grace F,

Margaret B, John B - about 1910

The story of our female ancestors when

the historical records don’t help

A

Misrepresentation

From our

twenty first century perspective, the predominance of the historical records on

the achievements of the menfolk is stark. It is obvious that the historical

record is heavily weighted and focused on male activity and often barely

notices the lives, ordeals, achievements, and family bonding provided by our

female ancestors. We know today, that the historical record provides us with a

biased view. This cannot be the reality. It is simply what was recorded.

As a

historian it is important to found our narrative on the evidence which exists.

It is not open to us retrospectively to invent facts which do not exist. So the

approach to correct this imbalance in the record cannot be to portray a factual

record that simply does not exist.

However by

reflecting on the existing evidence, and applying a fresh analysis, we can

recover the story of the Farndale women, even though the underlying evidence

has not recorded everything they did. We don’t need to conjure a non existent factual narrative, but we can apply our own

experience and understandings to recover the place that we knew women played.

Patrilineal

heritage

We should

not blame the patrilineal system which records our family history for this

imbalance. As a former anthropologist, I know that the passage of a name

through the male line is not the only solution, and many societies particularly

in West Africa have adopted matrilineal systems, and others have adopted

multi-lineal systems such as clan systems. However the system adopted

throughout Europe is a patrilineal one. What is important to a family historian

is that there is structure, and the patrilineal nature of ancestry provides a

structure which allows us to peer deep into our history. Whilst theoretically

possible to explore every diverging family line backwards through time, that

would be impracticable. The unique locative nature of the Farndale name provides

a beacon, which we can follow through time, to find our history. It doesn’t

matter whether we still bear the Farndale name today, or are descended from a

relative however distant, who links into the Farndale chain, this family

history allows us to see far back to our more distant ancestry. It is no more

the history of modern folk bearing the name Farndale than a history of anyone

who is descended from this line of ancestry. The Farndale lineage provides a

tool to look back in time and no more. It would have worked the same if the

name had been passed down maternally, but it wasn’t, and the patrilineal

passage of the name is what allows our research to work.

In order to

keep this work finite, there is a page for every person who was born a

Farndale. The record is equally about female as male folk who were born with

the name. I have not recorded those who married into the Farndale family

separately, but have included their stories where I can. I have sometimes

explored maternal ancestry in a few instances, but this cannot be

comprehensive, or we would soon find ourselves following the story of all

mankind. The patrilineal lineage thus provides a system to record a single

family, both male and female, and to keep the research within some structure

and boundaries.

The

patrilineal system of lineage is not the cause of the misrepresentation of

women.

The

weighted record

What is

to blame for the evidential focus on the menfolk is the historical record

itself. The evidence used for historical research can only derive from the

historical record. It would be completely wrong for a historian to make up

historical facts that were not recorded. What we have to do is to start by

recording the existing historical evidence, to build the story of the family.

Inevitably it is evidence dominated by the male stories. Wherever there is

factual evidence of the lives of women, those facts are of course brought in to

our narrative. What we must then do, is to apply our own perspective of what

must have been. Of course even in deeper historical times, the women folk were

not invisible, but provided the bedrock of families through time.

Martin

Farndale recalled his experiences during the late 1930s, in the period

immediately before the Second World War. He remembered that about this time

there was much going on that I didn’t understand. My mother would come and sit

with me as I went to sleep at night and these moments became highlights of

those days. I adored her, she seemed to understand everything and she never

failed to set my mind at rest whatever my problems. I owe her a great deal

indeed. She ensured that we grew up with balance and understanding of other

people. My father, who I worshipped, represented all that was strong, good and

upright in life. He was direct, outspoken and reliable. I always felt nothing

could happen to us if he was there. We were unbelievably lucky with our

parents. Almost without knowing it they gave us all an ideal upbringing,

treating us all the same, insisting on standards, respect for them, and for the

law, yet with love and understanding which gave us great confidence.

The reality

of family life was far more balanced than the historical records tend to

portray.

Peggy

Farndale, a bedrock for her family

Women in

medieval society

There is

little doubt that women have played their stabilising role in families through

the epoch of time. We sometimes come across their names. We know that Nicholaus de

Farndale (c1332 to c1400) was married to Alicia, uxor ejus, his wife and they are both recorded as paying the

controversial poll tax, which led to the Peasants’ Revolt, in 1379. This was a

period of greater bargaining power for a new middle class, and perhaps that

came with a great recognition of some involvement of women in the new

opportunities, even if all that we see is the equal opportunity to pay tax. At

about the same time William

Farndale (c1332 to 1397) of Sheriff Hutton made a

bequest in his will and the residue of his estate was shared by his wife

Juliana and she was appointed as one of his executors.

Indeed if we

consider the lives of the royal and aristocratic families who no doubt led the

way in cultural norms, it is obvious that medieval women of this period were

often the real power behind their male puppets. The story of the period of the Wars of the

Roses has revealed that, in order to understand the politics behind the

dynastic struggles of that age, it is far more instructive to consider such

influencers as Joan

the Fair Maid of Kent, the power behind the reign of the hopeless

Plantagenet Richard II, at least until she died in 1385; Margaret

of Anjou, the power behind the reign of the equally hopeless Lancastrian

Henry VI, until outmanoeuvred by the Yorkist power grab in 1461, though with a

short counter offensive in 1470; Cecily

Neville, the mother and mentor of the Yorkist Kings Edward IV and Richard

III; Elizabeth

Woodville, the wife of Edward IV,

who attempted an unsuccessful power grab to protect her son Edward V against

the designs of Richard III, but whose daughter, Elizabeth of York married the

Tudor King Henry VII; and Lady

Margaret Beaufort, the mother of the Tudor King Henry VII, who she helped

to steer to his monarchy.

Enlightenment

The perception of women in society

ebbed and flowed over time. Women in the seventeenth century may have had a

degree of independence. Lady

Mary Wortley Montagu (1689 to 1762) became famous for her wit, her travels

and for introducing vaccination from Turkey. The Blue

Stocking circle was an informal intellectual association led by women in

the 1750s.

A new form of literary work emerged in

the eighteenth century, the novel, which focused on the lives of ordinary

people. The probable father was Daniel Defoe and Robinson Crusoe (1719),

with direct prose and vigorous narrative, and vice, danger and crime in Moll

Flanders (1722). Novels worked through the imagination of both author and

reader and inspired new worlds into which people could journey in their minds.

Victorian

attitudes

From the

late seventeenth century, there was a new appetite among populations beyond

basic needs, but with appetites for comfort, novelty and pleasure. People

consumed more of such commodities as tobacco, sugar, coffee, fresh bread,

alcohol and particularly tea. Spending more required people to work longer

hours. More married women took jobs.

This created

a world in which there were opportunities for greater economic and social

autonomy. Women in industrial Britain sometimes married later, often in their

twenties. The Poor Law may have reduced the need to have large families of

children as they were not solely dependent on children in old age. Single women

were sometimes recognised as independent of their male relatives. Women could

become heads of families and own businesses. By the Napoleonic Wars two thirds

of married women earned wages in trades such as retailing, lace making, brewing

and spinning.

It was often

the new earnings of young folk and married women which enabled the acquisition

of new luxuries. Yet there was also opportunity for greater exploitation.

As men’s

wages rose, working class mothers increasingly stayed at home. The Trade Unions

Congress founded in 1868 in Manchester expressly sought to allow wives to find

their proper sphere at home. Women in turn took on a role of moral superiority

in the home. No doubt men were demanding

higher pay and using their breadwinner status to exclude women. Mothers

concentrated on domestic comfort, nutrition and health. They sometimes

controlled the family budget and handed out pocket money, but that was not

always so.

Many

husbands boasted that they never asked their wives what they did with the

money. As long as there was food enough, clothes to

cover everybody, and a roof over their heads, they were satisfied, they said,

and they seemed to make a virtue of this and think what generous, trusting,

fine-hearted fellows they were. If a wife got in debt or complained, she was

told: 'You must larn to cut your coat accordin' to your cloth, my gal.' (Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter

III, Men Afield)

Women often

became organisers of an informal local mutual assistance regime across extended

families, giving a cup of sugar or packet of tea to a neighbour when it was

needed.

Death tolls

fell after 1880. Children were better fed. Children born in long term marriages

fell from 6 to 4 between the 1860s and 1900s. Marriage was often delayed.

Attitudes

changed and the reality of life no doubt varied between families.

A few of

the younger, more recently married women who had been in good service and had

not yet given up the attempt to hold themselves a little aloof would get their

husbands to fill the big red store crock with water at night. But this was said

by others to be 'a sin and a shame', for, after his hard day's work, a man

wanted his rest, not to do ''ooman's work'. Later on

in the decade it became the fashion for the men to fetch water at night, and

then, of course, it was quite right that they should do so and a woman who

'dragged her guts out' fetching more than an occasional load from the well was

looked upon as a traitor to her sex. (Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter I, Poor People's Houses)

A few

women still did field work, not with the men, or even in the same field as a

rule, but at their own special tasks, weeding and hoeing, picking up stones,

and topping and tailing turnips and mangel; or, in

wet weather, mending sacks in a barn. Formerly, it was said, there had been a

large gang of field women, lawless, slatternly creatures, some of whom had

thought nothing of having four or five children out of wedlock. Their day was

over; but the reputation they had left behind them had given most country-women

a distaste for 'goin' afield'. In the 'eighties about

half a dozen of the hamlet women did field work, most of them being respectable

middle-aged women who, having got their families off hand, had spare time, a

liking for an open-air life, and a longing for a few shillings a week they

could call their own.

(Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter III, Men Afield)

To spend

their evenings there

(the Wagon and Horses Inn) was, indeed, as the men argued, a saving, for,

with no man in the house, the fire at home could be let die down and the rest

of the family could go to bed when the room got cold. So the men's spending

money was fixed at a shilling a week, sevenpence for the nightly half-pint and

the balance for other expenses. An ounce of tobacco was bought for them by

their wives with the groceries. It was exclusively a men's gathering. Their

wives never accompanied them; though sometimes a woman who had got her family

off hand, and so had a few halfpence to spend on herself, would knock at the

back door with a bottle or jug and perhaps linger a little, herself unseen, to

listen to what was going on within. Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter IV,

At the ‘Wagon and Horses’.

Of course Victorian

women could be subject to abuse. In December 1883 at a hearing in the divorce

of a well known actor, brought by the husband,

better known as “Mr

Arthur Dacre”, the actor, for a divorce by reason of his wife's adultery

with the three co respondents. Answers had been filed denying the charge, and

there were counter allegations. Ellen Crouch, examined by Dr Tristram QC, said

that for some time she was in the service of Mrs James. Have you at any time

committed adultery with Mr O'Neill, Mr Clifford, or Mr. Brooks? Certainly not.

Cross examined by Mr. Clark: In 1877 my husband was in trouble about his

practise. His mother and brother died within a short time of one another. A

patient had also complained of his partner. He took opium and chloral. In 1878

I made complaints of his violence and showed the bruises to Martha Farndale.

I think I wrote to Miss Paley, and I did so to my mother. On November 18th I

called the attention of my husband's brother to the state I was in. When he

threw me across the railway carriage I had used the word “disgrace” twice in

reference to a marriage in his family. I complained of Mrs Swain to my husband.

How soon did you find the fatal influence that you say was hostile to you? Very

shortly. Did you before on the night of October 6, 1877 believe that adultery

had been committed? I did.

Girl’s

Employment

After the

girls left school at ten or eleven, they were usually kept at home for a year

to help with the younger children, then places were found for them locally in

the households of tradesmen, schoolmasters, stud grooms, or farm bailiffs.

Employment in a public house was looked upon with horror by the hamlet mothers,

and farm-house servants were a class apart. 'Once a farm-house servant, always

a farm-house servant' they used to say, and they were more ambitious for their

daughters. (Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter X, Daughters of the Hamlet).

Unmarried

women

In the

industrial era, there were rising premarital conceptions, from 15% to 40% over

the course of the eighteenth century. Births out of wedlock, which were

referred to as illegitimacy, rose from 1% to 5% of births. In all over

half of first born children were conceived out of wedlock. The trend then fell

sharply from 1850s to its lowest ever level in 1901.

The

hamlet women's attitude towards the unmarried mother was contradictory. If one

of them brought her baby on a visit to the hamlet they all went out of their

way to pet and fuss over them. 'The pretty dear!' they would cry. 'How ever can

anybody say such a one as him ought not to be born. Ain't

he a beauty! Ain't he a size! They always say, you

know, that that sort of child is the finest. An' don't you go mindin' what folks says about you, me

dear. It's only the good girls, like you, that has 'em;

the others is too artful!' But they did not want their own daughters to have

babies before they were married. 'I allus tells my

gals,' one woman would say confidentially to another, 'that if they goes

getting theirselves into trouble they'll have to go

to th' work'us, for I won't

have 'em at home.' And the other would agree, saying,

'So I tells mine, an' I allus think that's why I've

had no trouble with 'em.' To those who knew the

girls, the pity was that their own mothers should so misjudge their motives for

keeping chaste; but there was little room; for their finer feelings in the

hamlet mother's life. All her strength, invention and understanding were

absorbed in caring for her children's bodies; their mental and spiritual

qualities were outside her range. At the same time, if one of the girls had got

into trouble, as they called it, the mother would almost certainly have had her

home and cared for her. There was more than one home in the hamlet where the

mother was bringing up a grandchild with her own younger children, the

grandchild calling the grandmother 'Mother'. If, as sometimes happened, a girl

had to be married in haste, she was thought none the worse of

on that account. She had secured her man. All was well. ''Tis but Nature' was

the general verdict. But though they were lenient with such slips, especially

when not in their own families, anything in the way of what they called 'loose

living' was detested by them. Only once in the history of the hamlet had a case

of adultery been known to the general public, and, although that had occurred

ten or twelve years before, it was still talked of in the 'eighties. The guilty

couple had been treated to 'rough music'. Effigies of the pair had been made

and carried aloft on poles by torchlight to the house of the woman, to the

accompaniment of the banging of pots, pans, and coal-shovels, the screeching of

tin whistles and mouth-organs, and cat-calls, hoots, and jeers. The man, who

was a lodger at the woman's house, disappeared before daybreak the next

morning, and soon afterwards the woman and her husband followed him. (Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter

VIII, the Box)

Suffrage

Between the 1790s women, particularly

the educated and religiously motivated, started to play a greater role in

public life. Florence Nightingale’s struggle against male incompetence in

hospitals and women’s involvement in protests against the Bulgarian horrors in

1876 including sexual violence and enslavement, and criticism of British policy

towards Boer women and children are examples. Very large numbers of women were

volunteer Torty and Liberal Party workers.

Women’s colleges, though not equal to

men’s, were established in Oxford and Cambridge in the 1870s and other

universities, led by London admitted women on more equal terms. Ther British

Medical Association admitted women in 1892.

There were growing professional

opportunities in medicine, teaching and social administration. There remained

strong taboos, even for croquet and especially bicycling. There was controversy

at the use of more practical ‘rational

dress’.

The Married

Women’s Property Act 1882 gave women the right to own and manage property

independently of their husbands.

As early as 1848, Disraeli felt that

if women could be head of state and landowners, she could certainly exercise

the vote. Smaller countries allowed women suffrage earlier, New Zealand in

1893, South Australia in 1895, and some US states such as Wyoming. It seemed a

bolder move for larger nations. In the 1890s and majority of Conservative and

Liberal MPs supported some degree of women’s suffrage. However they had other

priorities to contend with. There was opposition. Some working men feared that

women would close down their pubs.

There emerged a group of women who

were not willing to wait. In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst

and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst established the Women’s Social and Political Union.

In 1906 they moved to London. The Daily Mail nicknamed them the

Suffragettes. In January 1908 two women chained themselves to the railings of

No 10 Downing Street. They became inventors of the hunger strike. In 1909,

William Gladstone’s son, Herbert Gladstone, the Liberal Home Secretary,

authorised the force feeding of those on hunger strike and this drew widespread

repugnance.

There was support for a cross party

private member’s bill for women suffrage, but Parliament was dissolved over the

budget crisis. Two more bills failed in 1911 and 1912. There was a hostile response from the Suffragettes.

The Orchid House at Kew was smashed; Lloyd George’s house was bombed and in

1913 Emily Davison was fatally injured when she stepped in front of the king’s

hose at the Derby.

It may be that the suffragettes’

campaign was counterproductive, but it forced attention on suffrage, and may

have hastened it.

By 1914

Florence Farndale, Rev

William Edward Farndale’s wife, was president of the North Eastern

Federation of Suffragettes. On 23 March

1914 a very successful social evening was held at the Suffrage Rooms,

Birtley. Mrs Farndale presided. Miss Beaver and Miss Sheard gave two very

interesting speeches on the Suffrage Movement. Miss H Auton and Miss Elliott

provided a splendid musical programme, and the Rev F D Brooks also assisted by

giving two humorous recitations, which were much enjoyed. There was a very

large attendance. A plentiful supply of refreshments, which were provided by

the committee, were served during the evening. 20 new members were enrolled. On

April 16th, a members meeting was held at the suffrage rooms Birtley at which

Mrs C M Gordon spoke.

In April

1914, in asking why women need the vote, a meeting was held in the

Cooperative Hall, Birtley, on Friday night, under the auspices of the local non

militant Women's Suffrage Society. The Rev W E Farndale presided over a good

attendance. Miss Geraldine Cook, London, gave an address. She pointed out the

evils of sweating, which was so prevalent amongst women. This was largely due

to their low status, which would be raised if they were given the vote. The

burden of much present day social reform fell upon the shoulders of the mothers

of the nation, because politicians were content to tinker with effects rather

than causes. Where women had been granted the parliamentary franchise, the

result had been an improvement in the conditions of the workers, better

protection for the young, the emptying of prisons and workhouses, the raising

of the age of consent, and the lessening of the drink evil.

In March

1915 the sister hood at the Ouston Primitive Methodist Church was visited on

Wednesday week, by Mrs Farndale, the wife of the Primitive Methodist minister

of Birtley. She gave an interesting address on “The Ministry of Women”. A solo

was rendered in splendid style by Miss Fenwick of Ouston. After a very

satisfactory report had been given by Mrs Cook of the good work that has been

done by the Select Committee, a cup of tea was served round which brought a

very pleasant hour to a close.

In March

1916 the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies received a cable announcing

that our maternity hospital in Petrograd was opened on Monday by the grand

Duchess Cyril, Sir George and Lady Georgina Buchanan, and Madame Sazonoff being present at the ceremony. The donors

included Mrs Florence Farndale, 2s 6d. The total collected was £3,108 6s

10d.

The First World War suspended normal

politics, but British women achieved the vote when peace returned.

In 1918 the

Representation of the People Act was passed which allowed women over the age of

30 who met a property qualification to vote. Although 8.5 million women met

this criteria, it was only about two-thirds of the total population of women in

the UK. The same Act abolished property and other restrictions for men, and

extended the vote to virtually all men over the age of 21. Additionally, men in

the armed forces could vote from the age of 19. The electorate increased from

eight to 21 million, but there was still huge inequality between women and men.

At the

Ladies Missionary Auxiliary in January 1929 “Forward be our watchword” was

the clarion call with which Mrs Farndale concluded her address at the meeting

held on Wednesday afternoon in the Primitive Methodist Church. The address

throughout was very interesting and greatly enjoyed. Mrs Abbott presided over

the meeting.