|

|

Education

How our ancestors were educated

|

|

Farndales and

education

Alfred

Farndale’s memories of school at the turn of the twentieth century: “I

remember going to school at Charltons near Tidkinhow. We then

went to Standard 1 at Boosbeck. We

stayed there until we were 14. It was a two mile walk each day. The headmaster

was Mr Ranson. I remember Jim, my elder brother catching me fishing and playing

truant. He just said "Get in" (he was in a

pony and trap) and he took me to a day’s marketing at Stokesley. I remember the

second masters name was Ackroyd. I got a fork through my leg

and he sucked it out. We were always inspected as we arrived at school. We had

to walk past the Bainbridge place and people used to say that he had more sheep

on the moor than he was allowed. I remember William

looking after me at mother's funeral. I was crying and very upset.”

Rosamund

Farndale (FAR00920),

born 1931 (later Rosamund Martin and Rosamund Kwalker

Pomevie) from Northumberland became a headmistress in

Hampstead, London.

In a talk between Alfred Farndale and his son, Martin on 29 July 1982, Alfred Farndale (FAR00683) recalled, "I remember going to school at Charltons near Tidkinhow. We then went to Standard 1 at Boosbeck. We stayed there until we were 14. It was a two mile walk each day. The headmaster was Mr Ranson. I remember Jim, my elder brother catching me fishing and playing truant. He just said "Get in" (he was in a pony and trap) and he took me to a days marketing at Stokesley. I remember the second masters name was Ackroyd. I got a fork through my leg and he sucked it out. We were always inspected as we arrived at school. …”

His son

Martin Farndale (FAR00911)

recalled: Every day Anne and I, and later Geoffrey as well, were driven into

Northallerton, which was five miles away, to school and we were collected in

the evening. School was a very new adventure and not easy going for me. Mrs

Lord was a hard but far task master, insisting on high standards. Much was

learnt by heart – poems, hymns and tables. Mr Lordtaught history ad geography

and these quickly became my favourite subjects. On Friday afternoons the school

walked in a long crocodile to the village of Romanby,

there to sit and watch lantern slides given by a Mr and Mrs Linton about their

travels to the Holy Land and Egypt. These were wonderful, hazy black and a browny colour and white, but they opened

up the idea of travel and excitement. They also taught us a great deal

and left a deep impression on me. It was at Wensley House school that I made my

first friends. Richard Sawfell was the son of the

county surveyor whose mother knew my mother before they were both married.

David Ramsden was the son of a farmer near Northallerton. Jack Errington came

with his mother during the school holidays to stay with his Grandmother

in Thornton-Le-Moor.

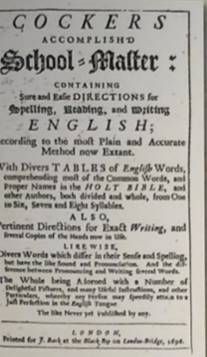

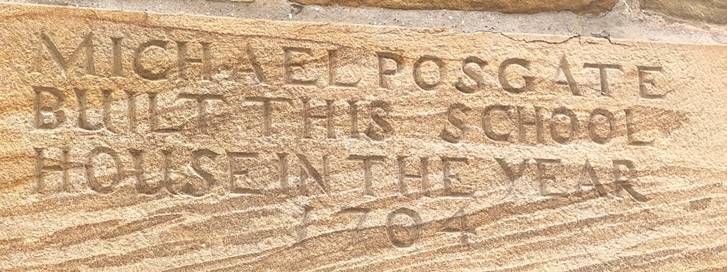

Eighteenth century education

Charity schools

In the early eighteenth century many

charity schools were founded to teach poorer children. Before this schools were

mainly for the middle and upper classes.

Some charity schools provided board and

lodging. Most were small schools such as the Postgate School in Great Ayton,

which is today a museum in Great Ayton.

Charity schools gave the poor their only chance of schooling. James Cook

may never have gone on to achieve as he did without the opportunity to break

away from his farming background. Some contemporaries objected to the education

of the poor arguing that “The ore a shepherd and ploughman know of the world,

the less fitted he’ll be to go through the fatigue and hardship of it with

cheerfulness and equanimity.”

The curriculum

Most of the teaching in charity schools

was one to one. The teacher would listen to a child recite or read, or test by

questions and answers, while other children got on with their work. The main

purpose of charity schools was religious education so pupils were taught to

read so that they could read the Bible and prayer books. Those who stayed on at

school may have learnt to write.

Children had to spend many hours at

their copybooks, copying out letters or words written for them at the top of

the page by the teacher.

They were also taught the basics of

arithmetic.

An eighteenth century engraving of a

charity schoolroom

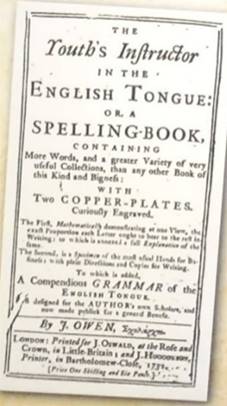

Reading

Reading and writing were taught

separately and reading came first. Books were scarce, learning to read started

at an oral skill, an exercise in memory. Children had to say aloud letters and

syllables, and also spell long and complicated words

before they learnt to read stories from books.

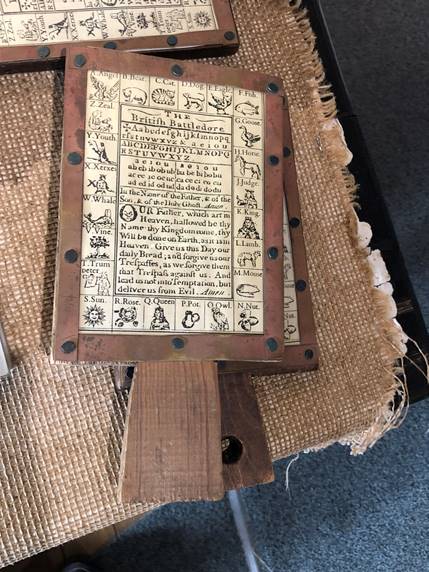

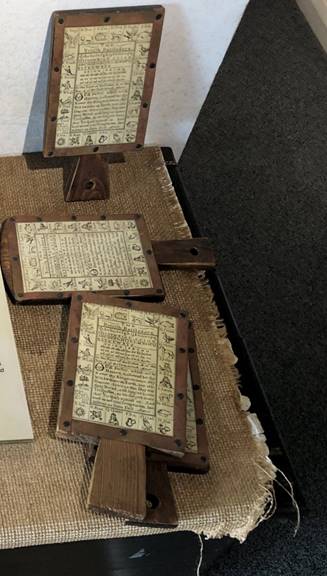

They started off with a hornbook, and then

went on to the spelling book which contained long lists of words with one

syllable, then two syllables etc. All these had to be mastered first.

Only when pupils were

considered to be ready, were they allowed to read passages from the

Bible or another book that was often used was Aesop’s Fables.

Hornbooks

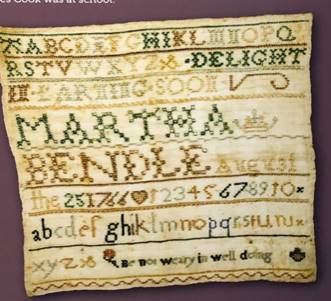

The education of girls

In the eighteenth century, literacy in

England amongst women was lower than for men. If they went to school at all,

girls tended to leave as soon as they could read. At home they learnt household

skills from their mothers and gradndothers. These ight include cokking and

preserving food, needlework, knitting and spinning flax as Ayton was a local

centre of the linen industry.

Victorian education

In early Victorian

Britain, many children did not go to school, which had not yet become

compulsory. Children from poorer families often worked. Poorer families often

relied on their children to bring in extra money that they needed to survive.

Girls, whether rich or poor, tended not to go to school in early Victorian

times. With the exception of a small number of very

wealthy girls who attended boarding school, most girls either worked if they

were poor or if they were wealthy were taught by a governess at home.

The Victorian governments

made gradual steps towards a more robust schooling system in Britain. In 1839,

the first groups of school inspectors were employed.

Families living in the big cities around Britain found it

particularly difficult to send their children to school because of the fees

they would have to pay as well as losing the income that their children would

bring in if they were working.

In the mid-1840s, the idea

of Ragged Schools, a type of volunteer-led school, spread to London. They were

the only possibility of education for those families who had been turned away

from other charitable or church schools and who couldn’t pay for their children

to learn. Children who went to Ragged Schools tended to be poor and commonly

came from families where parents were abusive or drunks. Some pupils were

orphans and some pupils’ parents were in prison so

they had taken to sleeping on the streets. The Ragged Schools gave free meals

and clothing to their pupils and taught them a trade such as shoemaking or

domestic skills.

In 1846 the government began to help pay for teacher training

too, which would serve to help more teachers get the training they needed to

successfully teach this generation of young people who were to, one day, lead

the country to new heights

By the 1860s, more than

40,000 of London’s poorest children were taught at Ragged Schools and by 1861, there

were lots more schools available for children to attend, generally set up by

individuals or organisations, but most of them not free. Although there were no

schools fully funded by the government yet, parliament was allocating more

money than ever for education in the 1860s. The annual funding for schools at

this time was more than £800,000. In 1862, parliament also made it compulsory

for head teachers to keep daily and weekly records of what happened at their

school in a log book. This was a good way to check

that progress and attendance were being monitored. Head teachers were being

made more responsible for the students under their care. However, with no laws

still to make children attend, progress was difficult and was not helped by a

continued lack of teaching resources and staff.

In 1857 Hughes’ Tom Brown’s

Schooldays immortalised Dr Thomas Arnold’s Rugby

School of the 1830s. A focus in public schools emerged of the relative autonomy

of boys, training for adult life. Grammar schools were cheaper and non boarding, and publicly funded Board schools copied

their ethos. There was an emphasis on games, toughness, independence

and a code of silence which tolerated bullying.

Stories for children were spawned by

Thom Brown, such as Kipling’s Stalky and Co in 1899.

The Education Act 1870 initiated a

national system of Elementary Schools, run by elected School Boards. This was

opposed by non conformists

as it gave financial support to Anglican and Catholic schools. It was

criticised for its narrow curricula, but working class

parents were generally enthusiastic. Most remembered their teachers positively.

Teaching included the 3Rs and English literature.

Literacy rose steadily from the 1830s

and very sharply from the 850s (55%) to the 1890s (about 90%).

(Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 514 to 515).

Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter II, A Hamlet Childhood:

There were not

many books in the house, although in this respect the family was better off

than its neighbours; for, in addition to 'Father's books', mostly unreadable as

yet, and Mother's Bible and Pilgrim's Progress, there were a few children's

books which the Johnstones had turned out from their nursery when they left the

neighbourhood. So, in time, she was able to read Grimms' Fairy Tales,

Gulliver's Travels, The Daisy Chain, and Mrs. Molesworth's Cuckoo Clock and

Carrots.

'Schools be the

places for teaching, and you'll likely get wrong for him doing it when

governess finds out.'

But that happy time of

discovery did not last. A woman, the frequent absences from school of whose

child had brought the dreaded Attendance Officer to her door, informed him of

the end house scandal, and he went there and threatened Laura's mother with all

manner of penalties if Laura was not in school at nine o'clock the next Monday

morning.

Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XI, School:

School began at nine o'clock, but the hamlet children set out

on their mile-and-a-half walk there as soon as possible after their seven

o'clock breakfast, partly because they liked plenty of time to play on the road

and partly because their mothers wanted them out of the way before

house-cleaning began. Up the long, straight road they straggled, in twos and

threes and in gangs, their flat, rush dinner-baskets over their shoulders and

their shabby little coats on their arms against rain. In cold weather some of

them carried two hot potatoes which had been in the oven, or in the ashes, all

night, to warm their hands on the way and to serve as a light lunch on arrival.

They were strong, lusty children, let loose from control; and there was plenty

of shouting, quarrelling, and often fighting among them. In more peaceful

moments they would squat in the dust of the road and play marbles,

or sit on a stone heap and play dibs with pebbles, or climb into the

hedges after birds' nests or blackberries, or to pull long trails of bryony to

wreathe round their hats. In winter they would slide on the ice on the puddles,

or make snowballs—soft ones for their friends, and hard ones with a stone

inside for their enemies. After the first mile or so the dinner-baskets

would be raided; or they would creep through the bars of the padlocked

field gates for turnips to pare with the teeth and munch, or for handfuls of

green pea shucks, or ears of wheat, to rub out the sweet, milky grain between

the hands and devour. In spring they ate the young green from the hawthorn

hedges, which they called 'bread and cheese', and sorrel leaves from the

wayside, which they called 'sour grass', and in autumn there was an abundance

of haws and blackberries and sloes and crabapples for

them to feast upon. There was always something to eat, and they ate, not so

much because they were hungry as from habit and relish of the wild food. At

that early hour there was little traffic upon the road. Sometimes, in winter,

the children would hear the pounding of galloping hoofs and a string of

hunters, blanketed up to the ears and ridden and led by grooms, would loom up

out of the mist and thunder past on the grass verges. At other times the steady

tramp and jingle of the teams going afield would approach, and, as they passed,

fathers would pretend to flick their offspring with whips, saying, 'There!

that's for that time you deserved it an' didn't get it'; while elder brothers,

themselves at school only a few months before, would look patronizingly down

from the horses' backs and call: 'Get out o' th' way,

you kids!' Going home in the afternoon there was more to be seen. A farmer's

gig, on the way home from market, would stir up the dust; or the miller's van

or the brewer's dray, drawn by four immense, hairy-legged, satin-backed

carthorses. More exciting was the rare sight of Squire Harrison's four-in-hand,

with ladies in bright, summer dresses, like a garden of flowers, on the top of

the coach, and Squire himself, pink-cheeked and white-hatted, handling the four

greys. When the four-in-hand passed, the children drew back and saluted, the

Squire would gravely touch the brim of his hat with his whip, and the ladies

would lean from their high seats to smile on the curtseying children. A more

familiar sight was the lady on a white horse who rode slowly on the same grass

verge in the same direction every Monday and Thursday. It was whispered among

the children that she was engaged to a farmer living at a distance, and that

they met half-way between their two homes. If so, it must have been a long

engagement, for she rode past at exactly the same hour

twice a week throughout Laura's schooldays, her face getting whiter and her

figure getting fuller and her old white horse also putting on weight. It has

been said that every child is born a little savage and has to

be civilized. The process of civilization had not gone very far with some of

the hamlet children; although one civilization had them in hand at home and

another at school, they were able to throw off both on the road between the two

places and revert to a state of Nature.

Fordlow National School was a small grey

one-storied building, standing at the cross-roads at the entrance to the

village. The one large classroom which served all purposes was well

lighted with several windows, including the large one which filled the end of

the building which faced the road. Beside, and joined

on to the school, was a tiny two-roomed cottage for the schoolmistress, and

beyond that a playground with birch trees and turf, bald in places, the whole

being enclosed within pointed, white-painted palings.

The average attendance

was about forty-five.

Every morning, when

school had assembled, and Governess, with her starched apron and bobbing

curls appeared in the doorway, there was a great rustling and scraping of

curtseying and pulling of forelocks. 'Good morning, children,' 'Good morning,

ma'am,' were the formal, old-fashioned greetings.

Reading, writing,

and arithmetic were the principal subjects, with a Scripture lesson every morning,

and needlework every afternoon for the girls.

Every morning at ten

o'clock the Rector arrived to take the older children for Scripture. He

was a parson of the old school; a commanding figure, tall and stout, with white

hair, ruddy cheeks and an aristocratically beaked

nose, and he was as far as possible removed by birth, education, and worldly

circumstances from the lambs of his flock. He spoke to them from a great

height, physical, mental, and spiritual.

His lesson consisted of

Bible reading, turn and turn about round the class, of

reciting from memory the names of the kings of Israel and repeating the Church

Catechism.

The writing lesson

consisted of the copying of copperplate maxims.

History was not

taught formally.

There were no

geography readers.

Those children who read

fluently, and there were several of them in every class, read in a monotonous sing-song, without expression, and apparently without

interest.

It must be remembered

that in those days a boy of eleven was nearing the end of his school life.

Miss Holmes carried her

cane about with her. A poor method of enforcing discipline, according to modern

educational ideas; but it served. It may be that she and her like all over the

country at that time were breaking up the ground that other, later comers to

the field, with a knowledge of child psychology and with tradition and

experiment behind them, might sow the good seed.

'Oh, Laura! What a

dunce you are!' Miss Holmes used to say every time she examined it.

Lark Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XII, Her Majesty’s Inspector:

Her Majesty's

Inspector of Schools came once a year on a date of which previous notice had

been given.

Her Majesty's Inspector

was an elderly clergyman, a little man with an immense paunch and tiny grey

eyes like gimlets. He had the reputation of being 'strict', but that was a mild

way of describing his autocratic demeanour and scathing judgement. His voice

was an exasperated roar and his criticism was a blend

of outraged learning and sarcasm. Fortunately, nine out of ten of his examinees

were proof against the latter. He looked at the rows of children as if he hated

them and at the mistress as if he despised her. The Assistant Inspector was

also a clergyman, but younger, and, in comparison, almost human. Black eyes and

very red lips shone through the bushiness of the whiskers which almost covered

his face. The children in the lower classes, which he examined, were considered

fortunate.

What kind of a man the

Inspector really was it is impossible to say. He may have been a great scholar,

a good parish priest, and a good friend and neighbour to people of his own

class. One thing, however, is certain, he did not

care for or understand children, at least not national school children.

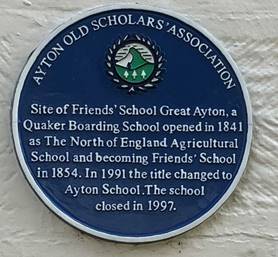

Education in Great Ayton

By the late 1860s, lots

more voluntary schools had been opened. Many working-class children now went to

school for some of their childhood. Even though some children still did not

attend school, this was now a minority. It became clear was that more schools

were needed. There was still an unacceptable amount of illiteracy in Britain

and those children who lived in the urban slums and more remote areas still weren’t able to access a school. Britain was going through

an amazing, prosperous period of industrialisation and the British Empire was

growing. There was a serious need to educate all the British people to help

drive Britain forward and be able to show off its citizens to the World. These

young people were the future of Great Britain, the then capital of the World.

The days were gone in which it was acceptable to worry that by letting poorer

children go to school to learn they would become unhappy with their social

standing.

In 1870, the government

passed an Education Act to deal with the education of Britain’s young

generation. It had been decided that it was crucial for the future of the

country and its citizens that education be provided throughout the nation.

Every child was to be given a place at school and school buildings had to be of

a reasonable quality. Head teachers now had to be qualified too. Schools

throughout the nation were inspected and checked to make sure that the

education they were offering met the new standards. New rules now meant that

school boards could make school compulsory for children between five and ten

years old and later thirteen.

Over the next ten years, new schools were set up in areas

where there had been none before making education accessible for everyone.

School boards were set up to manage and build these.

The next big step towards

education becoming compulsory came in 1880 with the Elementary Education Act.

Ten years had passed during which school boards had been given the choice over

whether to make children go to school. Now, the government had taken the

decision out of their hands: these new laws meant that every child had to

attend school.

One of the most important Education Acts to be passed towards

the end of the century was the 1891 Elementary Education Act. This established

new rules declaring that elementary education was to be free for all and not

just for those in severe poverty.

What school was like

Unlike school today, as a

Victorian child you could expect to be cold at school as there may not have

been a fire to heat your room or school hall. If there was, you may have been

sat so far away that the warmth didn’t reach you! Having most probably walked

to school, you might spend much of your time in wet, cold clothes from your

journey in depending on the time of year and you would certainly be tired –

sometimes, children would have to walk a long way to school! When you got

there, you would fully expect to be inspected by your teacher and would have to

be smartly turned out. Respect for your teacher was very important and you

would bow or curtsy to them during registration.

Lessons would be in the three ‘R’s: Reading, writing and

arithmetic. Sometimes, schools would teach geography, history and ‘drill’, the

Victorian equivalent of PE. You probably wouldn’t have had your own books;

instead, they would be shared among the whole class and kept by the teacher on

his or her desk, which would be at the front of the room. Depending on which

school you went to, you may or may not have a break time! During lessons, you

would be expected to pay attention and work to a high standard. If you made a

mistake, such as a wrong spelling or even writing with your left hand,

punishments would either be painful or humiliating and might be either a sharp

rap across the knuckles with a cane or being sent to the corner to wear the

dunce’s cap – often with your face to the wall in shame. If you accidentally

fell asleep in class, you could expect to receive a nasty snap of the master’s

ruler or perhaps even being woken up with some very cold water

Twentieth century education

The Education

Act 1944 (The Butler Act) established tripartite education system of

grammar schools, secondary modern schools and technical schools. The change was

led by the Tory, R A Butler. It set up a new Ministry of Education with hundreds

of small Local Education Authorities,. The new model

was based on three types of state secondary education – grammar, technical and ‘secondary

modern’, driven by a single aptitude test, the eleven plus, at age 11, which

were intended to work together with the types of school often located together.

It never worked as intended and in practice left a divide between grammar and secondary

modern schools.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the history of education which

examines whether its modern purpose is to teach us the nature of reality, or to

give us the tools to deal with it.