|

|

Our Farndale ancestors and the Robin Hood Legends

Exploring the connections between our Farndale outlaw ancestors and the legends of Robin Hood

|

|

Contents and

structure of this webpage

This

webpage has the following section headings:

- The

idea of Robin Hood

- The geography of the Robin Hood legend

- The Robin

Hood stories and local ecclesiastical links

- Campsall

- Ancestral

Farndales and the idea of Robin Hood – actors and story tellers

- Our

rebellious ancestors

- Dick

Turpin

- Other

references

- Links, texts and books

Dates

are in red.

Hyperlinks

to other pages are in dark

blue.

Headlines

are in brown.

References

and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual

history is in purple.

The idea of Robin Hood

An idea had

crystalised into stories by the mid thirteenth century, about the outlaw Robehod.

By the fifteenth century those compound stories, with a stock character

encountering various formulae of adventure, had evolved into more formal tales

of Robin Hood, a forest outlaw.

The first

surviving written stories date to about 1450 by which time there were large

numbers of rymes, some of which have survived (Robin Hood and the

Monk, Robin Hood and the Potter; Richard

Morris, Yorkshire a Lyrical History of England’s Greatest County, 2018,

184). Robin Hood was then portrayed as a yeoman

(I shall you tel of a gode yeman, His name was Robyn Hode – The Gest, Fytte 1, 1) and characters such as Maid

Marion and Friar Tuck had not yet emerged. By then he lived in a green wood

with merry men, including Little John, Will Scarlock and Much the miller’s son.

The sheriff of Nottingham was their nemesis. They hunted the king’s deer,

although they were loyal to the King. They were selectively anti clerical.

Friar Tuck was

a real outlawed priest, Frere Tuck, of the 1400s.

Maid Marion was

a character from French literature, and was added

later.

The association

with Robin Hood and Richard the Lionheart set the story in the 1190s, but this

was a later elaboration of John Major, a Scottish

historian, in the sixteenth century, later enhanced by Walter Scott in Ivanhoe

in 1819.

In the late

fifteenth century, the tales were brought together into A Gest of Robyn Hode

(“the Gest”), which was structured into sections or fyttes.

Various editions of the Gest were printed between 1490 and 1550.

The idea of

Robin Hood represents a nostalgic view of a past heroic age, of topsy turvy

justice, where justice was administered by the noble outlaws. The protagonists

of the tales were not real people, but as all epic literature, it provides a

contemporary record which emerged from historic events and experiences.

The

emergence of the Robin Hood stories in the 1400s was likely to have been

inspired in part by the complaints against oppression that led to the Peasants’ Revolt in

1381,

which itself was triggered by the imposition of three poll taxes in 1377, 1379

and 1381.

Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 128:

Popular Robin Hood stories, recited in verse by travelling minstrels, go

back to around the 1330s, they were referred to, disapprovingly, in Langland's

poem Piers Ploughman, c 1377, and were first written down in the early 1400s.

The stories traditionally originate in adjoining parts of Yorkshire and

Nottinghamshire. It has been suggested that if there ever was a real Robin Hood

(Robin Hod), he fought the Sheriff of Yorkshire between 1226 and 1234.

Robin Hood’s 700 year

survival into modern popular culture is unique.

There

is an In Our Time podcast on the centuries

old myth of the most romantic noble outlaw, Robin Hood and whether he was a yeoman, an

aristocrat, an anarchist or the figment of a collective imagination.

About

this time the memorable hero Robin Hood flourished in a romantic manner

(1066 and all that, Walter

Sellar and Robert Yeatman, 1930).

The geography of the Robin Hood legend

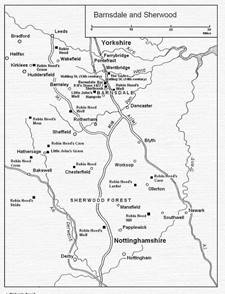

The earliest

references to Robin Hood are more associated with Barnsdale Forest than

Sherwood. Many of the names given to geographical locations in that area, such

as Robin Hood’s Well and Robin Hood’s cave, were given in the nineteenth

century. Some names though are much older, such as Barnsdale’s Stone of Robin

Hood (about 500m north of Robin Hood’s Well), which was mentioned as a boundary

marker in 1422 (John Leland, The Itinery in or

about the years 1535-1543 edited by L T Smith, London, Bell, 1909, 51;

Richard Morris, Yorkshire a Lyrical History of England’s Greatest County,

2018, 183; https://robinhoodlegend.com/monkbretton-priory-2/).

In Robin

Hood and the Monk the geography was focused on

Sherwood and Nottingham. Robin Hood and the Potter named Wentbridge (Went

breg) in Barnsdale. In Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, the action

took place in Barnsdale, and the sheriff was slain when he tried to flee to

Nottingham.

![]()

![]()

The Gest places

Robin Hood firmly in Barnsdale. It begins (Gest, Fytte I, 3):

Robyn strode

in Bernesdale,

And lenyd

him to a tre.

Barnsdale is a

constant reference in the Gest:

But as

they loked in to Bernysdale,

Bi a dernë

strete,

Than came a knyght ridinghe;

Full sone

they gan hym mete.

Now is the

knight gone on his way;

This game

hym thought full gode;

Whanne he

loked on Bernesdale

He blessyd

Robyn Hode.

(Gest, Fytte II, 57)

The same knight

later watched wrestling at Wentbridge:

He bare a launsgay in his honde,

And a man

ledde his male,

And reden

with a lyght songe

Vnto

Bernysdale.

But he went

at a bridge ther was a wrastelyng,

And there

taryed was he,

And there

was all the best yemen

Of all the

west countree.

(Gest, Fytte II, 81)

In a later part

of the story, Robin Hood intercepted two Benedictine monks on the highway north

of Doncaster:

But as

[t]he[y] loked in Bernysdale,

By the hyë

waye,

Than were they ware of two blacke monkes,

Eche on a

good palferay

(Gest, Fytte IV,130)

262.

He dyde

him streyt to Bernysdale,

Under the

grene-wode tre,

And he

founde there Robyn Hode,

And all his

mery meynë.

After Robin’s

royal pardon, when he was in royal service, he longeth sore for Bernysdale

(Gest, Fytte 8, 442)

439

Forth than went Robyn Hode

Tyll he came to our kynge:

'My lorde the kynge of Englonde,

Graunte me myn askynge.

440.

'I made a chapell in Bernysdale,

That semely is to se,

It is of Mary Magdaleyne,

And thereto wolde I be.

441.

'I myght never in this seven nyght

No tyme to slepe ne wynke,

Nother all these seven dayes

Nother ete ne drynke.

442.

'Me longeth sore to Bernysdale,

I may not be therfro;

Barefote and wolwarde I have hyght

Thyder for to go.'

We will return

later to Robin Hood’s longing to see his chapel of Mary Magdalene, when we meet

a direct ancestor of the modern Farndale family, William

Farndale, who was married at St Mary Magdelene’s church at Campsall, to

Margaret Atkinson, on 29 October 1564.

The King

allowed Robin to return to Barnsdale for a short time (Seven nyght I gyve

thee leve, No lengre, to dwell fro me.' Gest, Fytte 8,

443).

So Robin gratefully returned to Barnsdale

forest.

444.

'Gramercy, lorde,' then sayd Robyn,

And set hym on his kne;

He toke his

leve full courteysly,

To grene wode then went he.

445.

When he came to grene wode,

In a mery mornynge,

There he herde the notës small

Of byrdës mery syngynge.

446.

'It is ferre gone,' sayd Robyn,

'That I was last here;

Me lyste a lytell for to shote

At the donnë dere.'

447.

Robyn slewe a full grete harte;

His horne than gan he blow,

That all the outlawes of that forest

That horne coud they knowe,

So on his

return to the grene wode at Barnsdale, he slew a hart (as Roger milne

(miller) of Farndale (FAR000013A), son of Peter (FAR00008) had done in January 1293),

and gave a joyous blast of the horn he had made, so his merry followers would

know that he had returned. Robin then did not rejoin the King,

but returned to his old ways and lived in Barnsdale for another 22 years

until he was betrayed by the prioress of Kyrkësly

to her lover, the knight, Sir Roger of Donkestere.

450.

Robyn dwelled in grenë wode

Twenty yere and two;

For all drede of Edwarde our kynge,

Agayne wolde he not goo.

Kirklees Priory

was a Cistercian nunnery whose site is in the present-day Kirklees Park,

Clifton near Brighouse, Calderdale, West Yorkshire. The priory is featured in

the medieval legend of Robin Hood. According to Robin Hood's Death, Robin was

killed by the prioress of Kirklees. She was medically treating Robin by

bleeding, but treacherously drained too much of his blood instead.

Robin Hood’s

association with Barnsdale was more widely recorded. For instance

the Scottish poet and Augustinian canon Andrew of Wyntoun in his Orygynale Chronicle

of circa 1420 wrote in the Allusion (in book VII under the year 1283,

i.e. during the reign of Edward I):

litill Iohne and Robyne rude

Waichmen were commendit gud

In Yngilwod and Bernysdale,

And vsit þis tyme þer travale.

(Wemyss MS,

ll. 3453-56)

Litil Iohun and Robert Hude

Waythmen war commendit gud;

In Ingilwode and Bernnysdaile

Þai oyssit al þis tyme þar trawale.

(Cottonian

MS, ll. 3525-28)

"Yngilwod" is Inglewood forest in Cumberland. Wyntoun is the only writer

to locate Robin Hood's activities in that area. However

the reference to Barnsdale was more aligned to the wider tradition.

‘Robin Hood in Barnesdale Stood’ was

quoted by a judge in the court of Common Pleas in 1429 (Court of Common Pleas, 1429, 7 Henry 6).

The locations

with which Robin Hood is associated, like the stories themselves, are imagined

over centuries of storytelling. The places, like to stories, are ephemeral and

locating the green wood precisely is not the right approach to take. Yet there

is no doubt that the idea of the green wood has a very close association with

Barnsdale, Campsall, and the area immediately to the north of Doncaster. Robin

Hood’s domain, though flexible to the imagination of countless story tellers,

clearly stretched to Doncaster - My purpos was to haue dyned to day; At Blith or Dancastere (Gest,

Fytte 1, 22). Robin Hood’s ultimate betrayal was to the knight, Sir

Roger of Doncaster. Barnsdale forest was then at the eastern edge of the great

swamp land that dominated the land westward to the Humber estuary.

The parish

church at Campsall, still the Church of St Mary Magdalene, coincides with

Robin’s chapell in Bernysdale, That semely is to

se, It is of Mary Magdaleyne. There were several churches dedicated to Mary

Magdelene, including the parish church in Doncaster itself, but the church at

Campsall is the most likely association as it sits in the heart of the area

associated with Barnsdale.

The forest of

Barnsdale is somewhat intangible for a retrospective analysis, for there is no

forest at Barnsdale today. It seems likely that a large area around Campsall

was once forested. It may even have stretched past Doncaster to merge with

Sherwood (eg H L Gee, Folk Tales of Yorkshire,

London, Nelson, 1952, 48). The medieval records do not though suggest

forest at Barnsdale, at least of an administered nature, like Pickering,

with its forest verderers and regarders. Barnsdale or Bernysdale was known as a

lightly wooded area that was not officially a forest, but it was a place of

ambush in the fourteenth century. Highway robbery in Yorkshire in the

fourteenth and fifteenth century was a significant problem and there were

recorded holdups around Barnsdale and Wentbridge. There was at least one inn at

Wentbridge, where stories would have been retold. The area along the road from

Doncaster and Pontefract at that time, was likely a melting pot of

storytelling.

Yet the

references in the tales of Robin Hood and the grene wode to which he

returns is obviously associated with Barnsdale. Carey’s

map of Yorkshire 1754-1835 referred to Barnsdale Lodge (also known as

Barnsdale House) near the modern Barnsdale Bar on the A1 junction.

Richard

Morris, Yorkshire a Lyrical History of England’s Greatest County, 2018,

183 suggests: If the

Gest was designed to be recited in instalments, what if someone in the vicinity

adapted a selection of tales that were already widely known for a local

audience? If such a collection was then printed and began to circulate it would appear that the stories had originated around

Barnsdale.

Perhaps then

the written record which has been passed through the generations originated in Barnsdale, but arose from a collective memory of stories

from Barnsdale and from further afield.

There are hints

of the Robin Hood stories more directly associated with the North York Moors

and Kirkbymoorside. There are stories of Robin Hood’s butts above Robin Hood’s bay from where he fired an arrow that landed in

the bay, taken as a positive sign for the future seaside village. There are

other Robin Hood butts near Danby in Cleveland and associations with Castleton.

It was suggested that Robin Hood regularly fled the law at Robin

Hood’s bay and was given local shelter, sometimes heading out to sea with

the fishing boats. The English ballad The Noble Fisherman tells a story

of Robin Hood visiting Scarborough, taking a job as a fisherman, defeating

French pirates with his archery skills, and using half the looted treasure to

build a home for the poor. However, the ballad is only attested to in the 17th

century at the earliest.

There is also

recorded history of forest outlaws in such places as Pickering

forest.

The Robin Hood stories and local ecclesiastical links

Most English

writers of the fifteenth century had at least some association with the Church.

Those who captured the rymes of Robehod into the written word were

therefore likely to have had some ecclesiastical background.

Richard

Morris, Yorkshire a Lyrical History of England’s Greatest County, 2018,

183 surmises a likely

association of the stories with Barnsdale and Robin Hood’s chapel, dedicated to

Mary Magdalene. The original building resembled a collegiate church and was the

investment of two Norman families of the twelfth century, seeking a long term legacy. By the sixteenth century, there was a

vicar and a deacon at Campsall (Valor

Ecclesiasticus, Record Commission 1810 to 1834 v179). There were also

chantry priests in the vicinity who sang masses for the repose of the souls of

individuals who left endowments to the church. Morris suggests that the chantry

priests were supernumerary to the parish clergy and may have been involved in

teaching and he surmises that the first floor chamber

above the vaulted west bay of the south aisle at St Mary Magdalene, dating from

the late thirteenth century might have been a space used for such a purpose.

The emergence

of the theologian Richard of Campsall (1280 to 1350) suggests a well established tradition of teaching in Campsall. Richard

of Campsall (Ricardus de Campsalle) was an English theologian and scholastic

philosopher, at the University of Oxford. He was a Fellow of Balliol College

and then of Merton College. He is now considered a possible precursor to the

views usually associated with William of Ockham. He commented on Aristotle's

Prior Analytics, with emphasis on "conversion" and

"consequences". He is an apparent innovator in speculation about

God's foreknowledge, particularly concerning future contingents, around 1317.

By the

fifteenth century the villagers at Campsall had formed a fraternity,

and hired their own priest to pray for the parishioners living and

the souls departed (The Certificates of

Commissioners Appointed to Survey the Chantries, Guilds, Hospitals etc I, 200).

The references in the stories of Robin Hood, including Barnsdale, the Saylis

and Wentbridge suggest a very local knowledge of those who captured the stories

into writing. Doncaster

is just seven miles to the south. By 1540 its population was about 2,000.

The historian John

Paul Davis wrote of a connection between Robin Hood and

the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene at Campsall. Davis surmised that there is

only one church dedicated to Mary Magdalene within what might reasonably be

considered to have been the medieval forest of Barnsdale, being the church at

Campsall. The church was built in the late eleventh century by Robert de

Lacy, 2nd Baron of Pontefract. Indeed, a local legend suggests that Robin

Hood and Maid Marion were married at the church of Saint Mary Magdalene, at

Campsall.

Campsall

From early times the parish of Campsall

consisted of six townships or hamlets; Campsall,

Askern, Fenwick, Moss, Norton and Sutton. At the time of the Domesday survey in

1086, the area was in the possession of Ilbert de Lacy, the founder of

Pontefract Castle. The fact that Domesday does not mention a church here is no

proof that such did not exist, since cases are to be found where there is

similarly no such reference. Yet the existing church contains work of

pre-Conquest date; there may have been merely a chapel attached to the manor

without parochial rights. The earliest existing work in the church is of

twelfth century date.

In the reign of Edward

I Henry Lacy obtained a royal charter for a market at Campsall, which would

suggest that it was a place of some consequence by that time. By 1288 the

benefice was in the Taxatio of Pope Nicholas IV (1291) and had an annual value

of £66 13s. 4d. By a curious arrangement, the chapel of St. Clement in

Pontefract Castle had a share in tithe. The probable explanation of this

anomaly is the fact that Ilbert de Lacy and his successors held both estates

and adopted this method of supporting the chapel which was an important foundation in its own right. In 1336 there was a composition

under the sanction of the Archbishop of York in the name of Thomas de Bracton,

Rector of Campsall, and William de Mudene, Prebendary of the chapel, by which

one hundred shillings was to be paid by the Rector in lieu of the tithe.

A great change took place in 1481 when

Edward IV granted the rectory of Campsall to the Priory of Wallingwells in

Nottinghamshire, a small house of Benedictine nuns. In the following year

Thomas Rotherham, Archbishop of York, appropriated it to this purpose and

decreed that henceforth the benefice should be served by a Vicar, and gave the

appointment to Cambridge University. After the dissolution of the monasteries

under Henry VIII the rectorial tithes passed into lay hands.

St Mary Magdalene, Campsall is a large church

with at least two main phases of twelfth century building identifiable: at

first it had a cruciform plan; later, nave aisles enclosing a west tower were

added. Pevsner 1967, 154, says Campsall

church has ‘the most ambitious Norman west tower of any parish church in the

Riding’. Subsequently, alterations were made to the aisle arcades, windows,

chancel and south doorway. The church was restored between 1871 and 1877 by G.

G. Scott (Borthwick Institute Faculty Papers 1871/2

with plan) and piecemeal after. Restoration of stonework on the tower

was in progress in 2005. Romanesque sculpture is on the west doorway and tower;

one chancel window (inside and out); arches at the crossing; and numerous loose

and reset fragments.

Hunter 1831, 460, says 'Campsal church was the joint

work of the Lacis, the chief lords, and the Reineviles, the subinfudatories. It

exceded [the churches of Bramwith, Owston and Burgh] in magnificence as much as

it did in the extent of country that was attached to it'

The manor of Campsall thrived after the

Conquest, rather than retracting, and was largely owned directly by Ilbert de

Lacy (Hunter 1831, 463).

There were originally two rectors, one

appointed by each family; and this continued until about the time of Henry III

(Hunter 1831, 463).

Ancestral Farndales and the idea of Robin Hood – actors and story

tellers

Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 128: It has been suggested that if there ever was a real

Robin Hood (Robin Hod), he fought the Sheriff of Yorkshire between 1226 and

1234.

There are three aspects to the history

of the Farndale family which support a close association with the Robin Hood

stories.

First, the earliest records associated with our ancestors who

started to leave the dale itself, but adopted its name, provide us with a dozen

or so direct references to poachers and outlaws in Pickering Forest.

- Farndales

indicted for poaching in 1280 (FAR00019)

included Roger, son of Gilbert of Farndale, Nicholas de Farndale, William

the smith of Farndale, John the shepherd of Farndale, and Alan the son of

Nicholas de Farndale;

- Peter

de Farndale (FAR00008)’s

son Robert (FAR00012)

was fined at Pickering Castle in 1293. Robert son of Peter de Farndale, (FAR00012)(The Farndale 2

Line) was outlawed for hunting in 1293.

- Roger milne (miller) of Farndale (FAR000013A), son of

Peter (FAR00008) of Spaunton

on Monday in January 1293,

killed a soar and slew a hart with bows and arrows at some unknown place

in the forest. He with others were outlawed on 5 April 1293.

- Richard

de Farndale (FAR00016)

was excommunicated for stealing in 1316.

- Robert

of Farndale (FAR00024)

was fined at Pickering Castle for poaching in 1322.

- John

de Farndale (FAR00026)

was released from excommunication at Pickering Castle on 9 Apr 1324.

- Simon

de Farndale (FAR00021)

(The Farndale 4

Line), whose son Robert was fined at Pickering Castle in

1332.

- Robert

of Farndale (FAR00031)

was outlawed with others for hunting a hart in the forest in 1332.

- Nicholas

de Farndale (FAR00022)(The Farndale 3

Line) gave bail for Roger son of Gilbert of Farndale who

had been caught poaching in 1334 and 1335.

- William,

smith of Farndale (FAR00037)

on Monday 2 December 1336, came hunting in Lefebow with bow and arrows and

gazehounds………’

- Gilbert

de Farndale (FAR00018)

was bailed by Nicholas Farndale (FAR00022)

for poaching in 1344 and 1345.

- Commission

of oyer and terminer on 17 January 1348 to a long list of names including

William Smyth of Farndale (FAR00040)

the younger and Richard Ruttok of Farendale for breaking in to the park at

Egton, hunting and carrying away the property of the owner with deer, and

for assaulting the owner’s men and servants causing their inability to

work for a long time, for which they were fined 1 mark.

The emergence

of the Robin Hood stories in the 1400s was likely to have been inspired in part

by the complaints against oppression that led to the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381,

which itself was triggered by the imposition of three poll taxes in 1377, 1379

and 1381. It is notable that Nicholaus de ffarnedale

(FAR00838A)

paid 4d for the second Poll Tax in 1379, and may well have had rebellious

sympathies with these ideas.

Second, the family who called themselves

Farndale, by the early fourteenth century were focused around

Doncaster, and by the sixteenth century, were living in or around Campsall,

where Robin Hood had made a chapell in Bernysdale.

It seems

probable that the descendants of the outlaws of Pickering Forest were living in the area of Barnsdale at the same time that the rymes

were committed to writing, including in the form of the Gest.

The historical

record suggests that those individuals who left the dale, but adopted its name,

first headed south across the agricultural plains around York and settled in York

itself, around Sheriff

Hutton to the north of York and to the area around Doncaster

where William

Farndale was the chaplain immediately after the Black Death and then parish

vicar from 1397 to 1403.

The written

record is at least for the moment, cold, after 1403 until William

Farndale, son of Nicholas

Farndale and Agnes

Farndale, married Margaret Atkinson at St Mary of Magdalene, Campsall on 29

October 1564. We can then directly link William’s son, George

Farndale to all (or probably all) modern Farndales. It seems probable that

the direct ancestors of all modern Farndales therefore lived in or around

Campsall in 1564 before they emigrated north of the North York Moors to the

Cleveland area by 1567. It seems very likely that the family group who lived in

or around Campsall in the mid sixteenth century were the descendants possibly

of William

Farndale, the vicar of Doncaster himself, but very probably of his wider

family.

Third, the family who called themselves

Farndale, and who lived in the area of Barnsdale at that time, were probably

descended from the vicar of Doncaster, William

Farndale of the fourteenth century. If the church of St Mary Magdalene was

a centre of learning by the late thirteenth century, this places our family at

the same location where the stories of Robin Hood may well have first been

committed to writing. Given that they were likely descended from outlaws of Pickering

Forest, who poached for hart and soar in desperate acts of survival, they

had the inspiration to romanticise about their ancestors’ exploits.

There are other

associations with the Farndale’s ancestral past. Perhaps the oldest Robin Hood

story, which appears in the Gest, is that of a knight, Richard of the Lee who

had become indebted to the abbot of St Mary’s, York who threatened to possess

his lands. Robin Hood came to his aid by robbing the monks themselves to repay

the loan. It will be recalled from the

general history of the Farndales’ origins, that after the Norman Conquest,

the lands of Kirkbymoorside were the property of two rival baronial families,

the House Mowbray and the House Stuteville. Farndale was first mentioned as a

gift by Roger de Mowbray’s ward to the Cistercian abbey of Rievaulx. However the Stutevilles favoured the Benedictine monks of St

Mary’s Abbey in York and so in 1209 it was St Mary’s who had rights in the

forest of Farndale.

The Robin Hood

stories are well rooted in historical experiences, of which our Farndale

ancestors were players and direct witnesses.

In passing, it

is interesting to note that the valley which runs parallel to Farndale, and

with which it is closely associated in the medieval records, is Bransdale, and

it is tempting to draw some association with those around Campsall who later

named the area of Barnsdale. Only two letters shift!

It seems

probable that our ancestors were both the actors who, no doubt amongst many

like them, inspired the stories of Robin Hood, and may well have been amongst

those who passed down the stories and eventually recorded them to writing.

Our rebellious ancestors

Hence, we find

our family history in the heart of Robin Hood territory. There is a historical

documentary series on Sky television, called The

Britains, and episode 2 which depicts

two outlaws pursued in Pickering Forest whilst poaching for deer. They were

brothers called Philips, but they may as well have been Farndales. The

documentary observes that it was such folk who would inspire the legend of

Robin Hood, and their archery skills would one day comprise the successful

armies who fought at Crecy and Agincourt.

The medieval

sources record a significant number of our ancestors who were fined, outlawed

and even excommunicated, for poaching and illegally hunting, particularly

within the Royal Forest of Pickering. At the time they were petty

criminals, but they later became the heroic ‘merry men’, and there are plenty

of such characters in our history.

A historical

explanation for this activity might have been the struggles of the villein

classes in the thirteenth century and the Great Famine following bad weather

and poor harvests in 1315 which gave rise to widespread unrest, crime and

infanticide; followed by the Black Death which hit Yorkshire in March 1349.

A rebellious

trait is a seam which runs through the history of the English people and is

perhaps the origin of the democratic gains which were slowly achieved through

time. Our family’s association with this trait can be identified regularly in

the records. For instance John

William Farndale in 1936 was the youngest member of the Jarrow marchers.

As we learn

more about our ancestral history, this nostalgia for a world where justice and

fairness is administered by a noble outlaw on behalf

of the ordinary folk, weaves itself easily into the factual narrative of our

ancestors.

We cannot say

that our descendants were the fictional Robin Hood nor his merry men, but our

ancestral path weaves closely betwixt the idea of Robin Hood, and it seems

probable that our ancestors were those who inspired the tales and who, in later

generations, were close to those who wrote them down for posterity.

Other references

Yorkshire

is the Birthplace, refuge and burial place of Robin Hood (copied text for

further review)

Robin Hood of Wakefield

One theory of origin was proposed by

Joseph Hunter in 1852. Hunter identified the outlaw with a "Robyn

Hode" recorded as employed by Edward II in 1323 during the king's progress

through Lancashire. This Robyn Hode was identified with (one or more people

called) Robert Hood living in Wakefield before and after that time. Comparing

the available records with especially the Gest and also

other ballads, Hunter developed a fairly detailed theory according to which

Robin Hood was an adherent of the rebel Earl of Lancaster, defeated at the

Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322. According to this theory, Robin Hood was

pardoned and employed by the king in 1323. (The Gest does relate that Robin

Hood was pardoned by "King Edward" and taken into his service.) The

theory supplies Robin Hood with a wife, Matilda, thought to be the origin of

Maid Marian, and Hunter also conjectured that the author of the Gest may have

been the religious poet Richard Rolle (1290–1349), who lived in the village of

Hampole in Barnsdale. Hunter's theory has long been recognised to have serious

problems, one of the most serious being that "Robin Hood" and similar

names were already used as nicknames for outlaws in the 13th century. Another

is that there is no direct evidence that Hunter's Hood had ever been an outlaw

or any kind of criminal or rebel at all; the theory is built on conjecture and

coincidence of detail. Finally, recent research has shown that Hunter's Robyn

Hood had been employed by the king at an earlier stage, thus casting doubt on

this Robyn Hood's supposed earlier career as outlaw and rebel.

Robin Hood of York

The historian L. V. D. Owen in 1936 and

more recently floated by J.C. Holt proposed that the original Robin Hood might

be identified with an outlawed Robert Hood, or Hod, or Hobbehod, all apparently

the same man, referred to in nine successive Yorkshire Pipe Rolls between 1226

and 1234.There is no evidence however that this Robert Hood, although an

outlaw, was also a bandit.

The early ballads give a number of possible historical clues: notably, the Gest

names the reigning king as being an unnamed "Edward", but

unfortunately the ballads cannot be assumed to be reliable in such details.

This is of little help as in addition to King Edward I who took the throne in

1272 with an Edward on the throne until the death of Edward III in 1377, there

was also Edward the Elder (900–924), Edward the Martyr (975–978) and Edward the

Confessor (1042–1066)

Robin Hood as an alias

It has long been suggested, notably by

John Maddicott, that "Robin Hood" was a stock alias used by thieves.

What appears to be the first known example of "Robin Hood" as stock

name for an outlaw dates to 1262 in Berkshire, where

the surname "Robehod" was applied to a man apparently because he had

been outlawed. This could suggest two main possibilities: either that an early

form of the Robin Hood legend was already well established in the mid-13th

century; or alternatively that the name "Robin Hood" preceded the

outlaw hero that we know; so that the "Robin Hood" of legend was so

called because that was seen as an appropriate name for an outlaw.

Another theory identifies him with the

historical outlaw Roger Godberd, who was a die-hard supporter of Simon de

Montfort, which would place Robin Hood around the 1260s. There are certainly

parallels between Godberd's career and that of Robin Hood as he appears in the

Gest. John Maddicott has called Godberd "that prototype Robin Hood".

Some problems with this theory are that there is no evidence that Godberd was

ever known as Robin Hood and no sign in the early Robin Hood ballads of the

specific concerns of de Montfort's revolt.

Robin Hood, the high-minded Saxon yeoman

The idea of Robin Hood as an Anglo-Saxon

freedom fighter opposing oppressive Norman lords found popular appeal in the

nineteenth century. The most notable contributions to the idea are Sir Walter

Scott's Ivanhoe (1819) and Augustin Thierry's Histoire de la Conquête de

l'Angleterre par les Normands, A History of the Conquest of England by the

Normans (1825). Robin Hood appears as a character along with his "merry

men" in Ivanhoe, a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott published in 1820,

and set in 12th-century England. The character that Scott gave to Robin Hood in

Ivanhoe helped shape the modern notion of this figure as a cheery noble outlaw.

In the novel Robin is depicted as a follower of King Richard the Lionheart and

helps him and Wilfred Ivanhoe to fight against the Knights Templar. It is in

this work that the modern Robin Hood – "King of Outlaws and prince of good

fellows!" - as Richard the Lionheart calls him – makes his debut!

Academics indicate that there are a number of verifiable historical clues that allude to the

legend's Anglo-Saxon origins. In particular, The

Coucher Book of Selby Abbey, a manuscript dating from the eleventh century,

records that ‘a certain Prince of Thieves by the name of Swain, son of Sigge,

constantly prowled around Yorkshire's woods with his band on perpetual raids’.

The medieval chronicler speaks of how a 'cursed villain' in Swein's gang robbed

Abbot Benedict of Selby. J. Green indicates that Hugh fitz Baldric, the late

eleventh century Sheriff of Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire, held responsibility

for bringing Swein-son-of-Sicga to justice.[31] William E. Kapelle indicates

that Hugh fitz Baldric needed to travel around Yorkshire in the company of a small

army because of the threat that was posed to his safety by the region’s

outlaws. Historians indicate that the deeds of Yorkshire's eleventh century

outlaws, men such as Swein-son-of-Siccga, and their battles against the Sheriff

of Nottingham, merged together to form the legend that

is today universally known as The Adventures of Robin Hood.[33]

Yorkshire

Nottinghamshire's claim to Robin Hood's

heritage is disputed, with Yorkists staking a claim to the outlaw. In

demonstrating Yorkshire's Robin Hood heritage, the historian J. C. Holt drew

attention to the fact that although Sherwood Forest is mentioned in Robin Hood

and the Monk, there is little information about the topography of the region,

and thus suggested that Robin Hood was drawn to Nottinghamshire through his

interactions with the city's sheriff. And, the linguist Lister Matheson has

observed that the language of the Gest of Robyn Hode is written in a definite

northern dialect, probably that of Yorkshire.[48] In consequence, it seems

probable that the Robin Hood legend actually originates

from the county of Yorkshire. Robin Hood's Yorkshire origins are universally

accepted by professional historians.

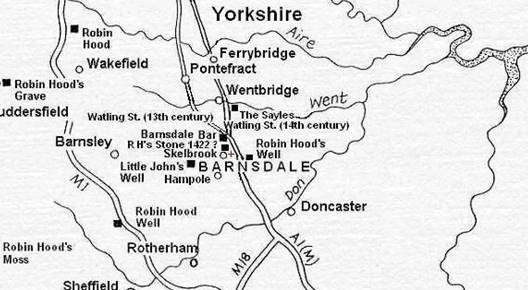

Barnsdale

A tradition dating back at least to the

end of the 16th century gives Robin Hood's birthplace as Loxley, Sheffield, in

South Yorkshire. The original Robin Hood ballads, which originate from the

fifteenth century, set events in the medieval forest of Barnsdale. Barnsdale

was a wooded area which covered an expanse of no more than thirty square miles,

ranging six miles from north to south, with the River Went at Wentbridge near

Pontefract forming its northern boundary and the villages of Skelbrooke and Hampole

forming the southernmost region. From east to west the forest extended about

five miles, from Askern on the east to Badsworth in the west. At the northern

most edge of the forest of Barnsdale, in the heart of the Went Valley, resides

the village of Wentbridge. Wentbridge is a village in the City of Wakefield

district of West Yorkshire, England. It lies around 3 miles (5 km) southeast of

its nearest township of size, Pontefract, close to the A1

road. During the medieval age Wentbridge was sometimes locally referred

to by the name of Barnsdale because it was the predominant settlement in the

forest. Wentbridge is mentioned in what may be the earliest Robin Hood ballad,

entitled, Robin Hood and the Potter, which reads, "Y mete hem bot at Went

breg,' syde Lyttyl John". And, whilst Wentbridge is not directly named in

A Gest of Robyn Hode, the poem does appear to make a cryptic reference to the

locality by depicting a poor knight explaining to Robin Hood that he ‘went at a

bridge’ where there was wrestling'. A commemorative Blue Plaque has been placed

on the bridge that crosses the River Went by Wakefield City Council.

The Saylis

The Gest makes a specific reference to

the Saylis at Wentbridge. Credit is due to the nineteenth century antiquarian

Joseph Hunter, who correctly identifed the site of the Saylis. From this

location it was once possible to look out over the Went Valley and observe the

traffic that passed along the Great North Road. The Saylis is recorded as

having contributed towards the aid that was granted to Edward III in 1346-47

for the knighting of the Black Prince. An acre of landholding is listed within

a glebe terrier of 1688 relating to Kirk Smeaton, which later came to be called

‘Sailes Close’. Professor Dobson and Mr Taylor indicate that such evidence of

continuity makes it virtually certain that the Saylis that was so well known to

Robin Hood is preserved today as ‘Sayles Plantation’.[55] It is this location

that provides a vital clue to Robin Hood’s Yorkshire heritage. One final

locality in the forest of Barnsdale that is associated with Robin Hood is the

village of Campsall.

The Church of Saint Mary Magdalene at

Campsall

The historian John Paul Davis wrote of

Robin's connection to the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene at Campsall. A Gest of

Robyn Hode states that the outlaw built a chapel in Barnsdale that he dedicated

to Mary Magdalene,

‘I made a chapel in Bernysdale, That seemly is to se, It is of Mary Magdaleyne, And thereto

wolde I be’.

Davis indicates that there is only one

church dedicated to Mary Magdalene within what one might reasonably consider to have been the medieval forest of Barnsdale, and that is

the church at Campsall. The church was built in the late eleventh century by

Robert de Lacy, the 2nd Baron of Pontefract. Local legend suggests that Robin

Hood and Maid Marion were married at the church.

The Abbey of Saint Mary at York

The backdrop of Saint Mary's Abbey at

York plays a central role in the Gest as the poor knight who Robin aids owes

money to the abbot.

Robin Hood's grave at Kirklees

At Kirklees priory in Yorkshire stands

an alleged grave with a spurious inscription, which relates to Robin Hood. The

fifteenth century ballads relate that before he died, Robin told Little John

where to bury him. He shot an arrow from the Priory window, and where the arrow

landed was to be the site of his grave. The Gest states that the Prioress was a

relative of Robin's. Robin was ill and staying at the Priory where the Prioress

was supposedly caring for him. However, she betrayed him, his health worsened,

and he eventually died there. The inscription on the grave reads,

'Hear underneath dis laitl stean

Laz robert earl of Huntingtun

Ne’er arcir ver as hie sa geud

An pipl kauld im robin heud

Sick [such] utlawz as he an iz men

Vil england nivr si agen

Obiit 24 kal: Dekembris, 1247'.

Robin Hood's Grave in the woods near

Kirklees Priory

The grave with the inscription is within

sight of the ruins of the Kirklees Priory, behind the Three Nuns pub in

Mirfield, West Yorkshire. Though local folklore suggests that Robin is buried

in the grounds of Kirklees Priory, this theory has now largely been abandoned

by professional historians.

All Saints church at Pontefract

A more recent theory proposes that Robin

Hood died at Kirkby, Pontefract. Drayton’s Poly-Olbion Song 28 (67-70) composed

in 1622 speaks of Robin Hood’s death and clearly states that the outlaw died at

‘Kirkby’.[59] Acknowledging that Robin Hood operated in the Went Valley,

located three miles to the southeast of the town of Pontefract, historians

today indicate that the outlaw is buried at nearby Kirkby. The location is

approximately three miles from the site of Robin’s robberies at the now famous

Saylis. In the Anglo-Saxon period, Kirkby was home to All Saints Church. All

Saints Church had a priory hospital attached to it. The Tudor historian Richard

Grafton stated that the prioress who murdered Robin Hood buried the outlaw

beside the road,

‘Where he had used to rob and spoyle

those that passed that way…and the cause why she buryed him there was, for that common strangers and travailers, knowing and seeing him

there buryed, might more safely and without feare take their journeys that way,

which they durst not do in the life of the sayd outlaes’.

In a similar fashion, the Gest reads,

‘Cryst have mercy on his soule, That dyed on the rode! For he was a good outlawe, And dyde

pore men moch god’.

All Saints Church at Kirkby, modern

Pontefract, which was located approximately three miles from the site of Robin

Hood’s robberies at the Saylis, accurately matches both Richard Grafton's and

the Gest's description because a road ran directly from Wentbridge to the

hospital at Kirkby.

The new church within the old. After All

Saints church was damaged during the civil war a new one was built within.

Robin Hood place-name locations

Within close proximity

of Wentbridge reside several notable landmarks which relate to Robin Hood. One

such place-name location occurred in a cartulary deed of 1422 from Monkbretton

Priory, which makes direct reference to a landmark named Robin Hood’s Stone

which resided upon the eastern side of the Great North Road, a mile south of

Barnsdale Bar.[63] The historians Barry Dobson and John Taylor suggested that

on the opposite side of the road once stood Robin Hood's Well, which has since

been relocated six miles north-west of Doncaster, on the south-bound side of

the Great North Road. Over the next three centuries, the name popped-up all

over the place, such as at Robin Hood's Bay near Whitby Yorkshire, Robin Hood's

Butts in Cumbria, and Robin Hood's Walk at Richmond Surrey. Robin Hood type place-names occurred particularly everywhere except

Sherwood. The first place-name in Sherwood does not appear until the year 1700,

demonstrating that Nottinghamshire jumped on the bandwagon at least four

centuries after the event.[64] The fact that the earliest Robin Hood type

place-names originated in West Yorkshire is deemed to be historically

significant because, generally, place-name evidence originates from the

locality where legends begin The overall picture from the surviving early

ballads and other early references[66] indicate that Robin Hood was based in

the Barnsdale area of what is now South Yorkshire (which borders

Nottinghamshire), and that he made occasional forays into Nottinghamshire.

The

tales of highwaymen in the seventeenth and eighteenth century were a

modernisation of Robin Hood.

Richard

Turpin

(baptised. 21 September 1705 – 7 April 1739) was an English highwayman whose

exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft.

Turpin may have followed his father's trade as a butcher early in his life but,

by the early 1730s, he had joined a gang of deer thieves and, later, became a

poacher, burglar, horse thief and killer. He is also known for a fictional

200-mile overnight ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess, a story

that was made famous by the Victorian novelist William Harrison Ainsworth

almost 100 years after Turpin's death.

Turpin's

involvement in highway robbery followed the arrest of the other members of his

gang in 1735. He then disappeared from public view towards the end of that

year, only to resurface in 1737 with two new accomplices, one of whom Turpin

may have accidentally shot and killed. Turpin fled from the scene and shortly

afterwards killed a man who attempted his capture.

Later

that year, he moved to Yorkshire and assumed the alias of John Palmer. While he

was staying at an inn, local magistrates became suspicious of

"Palmer" and made enquiries as to how he funded his lifestyle.

Suspected of being a horse thief, "Palmer" was imprisoned in York Castle, to be tried at the next

assizes. Turpin's true identity was revealed by a

letter he wrote to his brother-in-law from his prison cell, which fell into the

hands of the authorities. On 22 March 1739, Turpin was found guilty on two

charges of horse theft and sentenced to death. He was hanged at Knavesmire on 7 April 1739.

Turpin

became the subject of legend after his execution, romanticised as dashing and

heroic in English ballads and popular theatre of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Texts, links and

Books

POPULAR

BALLADS OF THE OLDEN TIME SELECTED AND EDITED BY FRANK SIDGWICK, Fourth Series. Ballads of Robin Hood

and other Outlaws, 1906, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28744/28744-h/28744-h.htm

REV.

EDWIN CASTLE (1843-1898) AND THE YORKSHIRE ROBIN HOOD (copied text for

further review) (One persistent legend attached to Campsall is that Robin

Hood and Maid Marian got married in St Mary Magdalene Church. There is a strong

claim amongst Robin Hood scholars that the legendary outlaw comes from

Yorkshire and not Nottingham. Based on the references to locations contained in

early versions of the Robin Hood stories, they argue that Barnsdale Forest is

the orginal, and Sherwood the imposter. And in one verse telling of the story,

Robin declares: I made a chapel in Barnsdale, That

seemly is to see, It is of Mary Magdalene, And there to would I be."

Campsall’s church is the only one in Barnsdale dedicated to St Mary Magdalene.

The wedding story was certainly widely told during Edwin’s tenure there. Unfortunately Maid Marian, like (perhaps) Sherwood, is a

later and fictional addition to the Robin Hood entourage. The historical Robin

Hood was in fact already married to a certain Matilda at the time of his

outlawing in 1322 (a time, incidentally, when for a very brief period the

sheriff of Nottingham had jurisdiction over Yorkshire).

Richard Morris, Yorkshire a Lyrical

History of England’s Greatest County, 2018.

Campsall bibliography

Arts Council of Great Britain: London,

Hayward Gallery, English Romanesque Art, 1066-1200, London, 1984

Borthwick Institute, Faculty papers,

Fac. 1871/2; Faculty Book 6, 18-19

Campsall, St Mary Magdalene guide, The

Story of St. Mary Magdalene Church, Campsall Yorkshire, n. p., 1965/1969

K. J. Conant, Cluny, Les églises et la

maison du chef d’Ordre, Mâcon, 1968

J. Fowler, “Note on the restoration of

the west doorway of Campsall church” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries

of London 8 (1879-81), 130-31

J. Hunter, South Yorkshire: The History

and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster, in the Diocese and County of York,

2 vols. J. B. Nichols & Son, London, 1828-31

J. E. Morris, The West Riding, 2nd ed.

London, 1923

N. Pevsner, Yorkshire: West Riding. The

Buildings of England, Harmondsworth, 1959, 2nd ed, Revised E. Radcliffe, 1967

Victoria County History: Yorkshire, II

(General volume, including Domesday Book) 1912, reprinted 1974

Other Notes

Yorkshire Archaeological

Journal, Vol 36