|

|

John Farndale

FAR00217

|

Yeoman farmer of Skelton, insurance agent, and writer John Farndale wrote extensively about Kilton and Saltburn by the Sea This page transcripts his writings |

Headlines of John Farndale’s life are in brown.

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

References

and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

John Farndale

was a prolific writer and the

writings of John Farndale can be found transcribed on another web page.

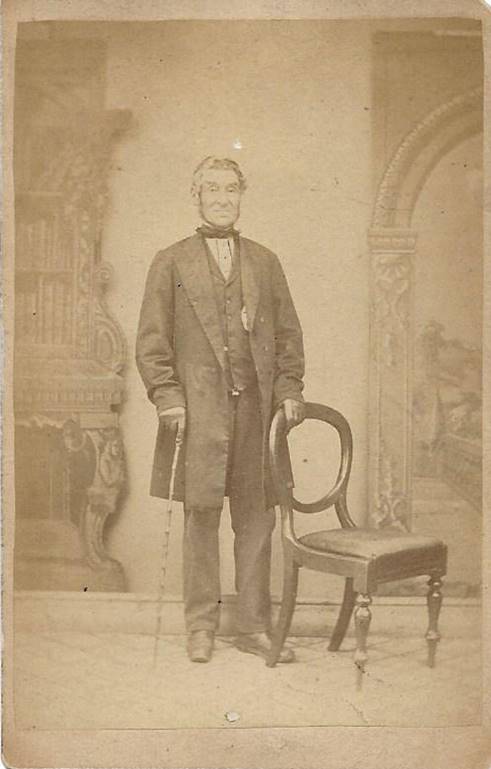

John Farndale with the photographer’s

logo on the reverse.

John Farndale

1791

John Farndale was born at Kilton in Cleveland,

Yorkshire on 15 August 1791, second son of William

& Mary (nee Ferguson) Farndale (FAR00183) of Kilton, baptised 9 October 1791, Brotton ( Brotton

PR & IGI). His father was a farmer and business person.

1793

In 1870, in The History of

the Ancient Hamlet of Kilton-in-Cleveland,

printed by W Rapp, Dundas Street, Saltburn 1870 , he later wrote: "My first remembrance began in my nurse's

arms when I could not have been more than 1 1/2 years old; a memory as vivid as

if it were yesterday. She took me out on St Stephen's Day 1793 into the current

Garth (a small enclosure) with a stick and 'solt' to kill a hare. A great day

at the time”.

1805

In 1870, in The History of

the Ancient Hamlet of Kilton-in-Cleveland,

printed by W Rapp, Dundas Street, Saltburn 1870 , he later wrote: Another time (some say, after celebrating

the victory of Trafalgar, 1805) he was dangling head foremost down the draw

well hanging by the buckle of his shoe. He goes on to describe a very happy

childhood and he clearly adored his mother.

"At this time I believe I loved God and was happy."

In 1805 (it is suggested that this was when

celebrating the Victory of Nelson at Trafalgar, though he would have been only

14 then) he fell down a well but was saved by his buckle – as he

later wrote:

I remember a draw well stood near the house of my father’s foreman. One day I

was looking into this well at the bucket landing, when I fell head foremost.

The foreman perceiving the accident, immediately ran to the well to witness, as

he thought, the awful spectacle of my last end. I had on at the time a pair of

breeches, with brass buckles on my shoes (silver ones were worn by my father and others), and to

his great astonishment, he found me not immersed in water at the bottom of the

well, but dangling head foremost from the top of a single brass buckle, which

had somehow caught hold.

Anyone directly descended from John, therefore owes their existence to a

shoe buckle!

He remembered "an old relation of my father"

(there were several in Kilton at that time) remarking that his elder brother

George was a "prodigal son",

while John was the son at home with his father. But John describes how he got

up to many frolics and had some narrow escapes, although he was no drunkard or

swearer.

His parents, he said, "were strict Church people and kept a strict look out. I became leader

of the (Brotton) church signers, clever in music" and he excelled his

friends. He had a close friend, a musician in the church choir. One day he met

him and said he had been very ill and had been reading a lot of books including

"Aeleyn's Alarum" and others "which nearly made my hair stand on

end." . His friend told him that he was going to alter his way of life and

if John would not refrain from his revelries, he would "be obliged to

forsake your company.". "That was a nail in a sure place. I was

ashamed and grieved as I thought myself more pious than he. Now I began to

enter a new life as suddenly at St Paul's but with this difference, he was in

distress for three days and nights but for me it was three months". He

fasted all Lent and describes his torment. "How often I went onto the hill

with my Clarinet to play my favourite tune."

Alleyn’s

Alarm was a pious text from the time.

His companion lived one

mile away (at Brotton perhaps?) and they met half way every Sunday morning at

6am for prayer. He remembered well meeting in a corner of a large grass field.

George (Sayer) began and he followed. When they finished they opened their eyes

to see "a rough farm lad standing

over us, no doubt a little nervous. Next day this boy said to others in the

harvest field 'George Sayer and John Farndale are two good lads for I found

them in a field praying.' " On the following Sunday they moved to a

small wood and met under an oak tree and met an old man who wanted to join

them. As usual George began and John continued when the old man began to roar

in great distress

1815

In 1815 (now 24), he was celebrating

victory at Waterloo:

From Kilton How Hill we have a fine view of the German ocean,

Skinningrove, Saltburn, Huntcliff, Roe-cliff, Eston Nab, Roseberry Topping,

Handle Abbey and Danby beacon. Here, too, at not much distance from each other,

may be seen no fewer than five beacons, formerly provided with barrels of tar

to give the necessary alarm to the people if Buonaparte at that period had

dared to invade our peaceful shores. After the great battle of Waterloo, and

Buonaparte had been taken prisoner, that glorious event was celebrated at

Brotton by parading his effigy through the street and burning it before Mr R

Stephenson’s hall, amidst the rejoicings of high and low, rich and poor,

who drank and danced to the late hour. The author formed one of a band of

musicians that played on the occasion, and he composed a song commemorating the

event, which became very popular in that part of the country. Brotton never

before or since saw the like of that memorable day.

I am grateful to Dr Tony Nicholson who has explained

that the hall was built by the Stephenson family in the 1780s after they had

made a fortune as woodmongers, trading in timber as a fuel source, and then

when timber became scarce, in coal. With the money from this trade, Robert

bought a third of the manor of Brotton, and then built ‘Stephenson’s Hall’.

When Robert Stevenson died in 1825, everything went to his

daughter, Mary, who had previously married Thomas Hutchinson, a master mariner

from Guisborough. Mary and Thomas settled in Stephenson’s Hall which soon

became Brotton Hall and over the years they bought various properties in

Brotton. Thomas was a close friend of John Walker Ord, the historian and poet

of Cleveland, and in 1843, Thomas invited Ord to join him on a picnic to Tidkinhow which was then part of Hutchinson’s dispersed property. Ord

composed a poem in honour of that day, which is transcribed at the Tidkinhow

page.

In The History of Kilton, With a Sketch of the Neighbouring

Villages, By the Returned Emigrant, Dedicated to the Rev William Jolley,

Toronto, Canada, America, Middlesbrough, Burnett & Hood, “Exchange”

Printing Offices, 1870, Redcar Cleveland Library Book No: R000040114

Classification: 942.854, Book No: R000040114, John Farndale wrote:

The church has been greatly improved, new slated roof and a most radical

change in the interior; the old pews and pulpit are all gone, and from the

walls Our Fathers’ prayer; the Belief; the ten commandments, in the xx chapter

of Exodus, saying “I am the Lord thy God which brought thee out of the land of

Egypt, out of the house of bondage; thou shalt have none other gods before me.”

Had I not seen those well known tablets of young Squire Easterby, of Skinngrove

Hall, and Wm Tulley , Esy of Kilton Hall, on beautiful white marble, I should

have been at a loss to have known the old church again. I looked at the place

where the old pulpit stood, and I remembered the ministers that once preached

Jesus and the resurrection, among them my old master, the Rev Wm Barrick, of

Lofthouse, - he would descend from the pulpit and join in the chorus of some

twenty voices, 57 years gone, when I had the happiness to be their chieftain.

The parishioners had … most gladly … and paraded down the mid street at the

celebration of the great battle of Waterloo, and burned before Mr Stephenson’s

Hall, when barrels of ale were given to the frantic multitudes, and the old

gentlemen danced and sang until day break, and here we find young Farndale,

once dangling at the mouth of the well, with his bugle and clarionet, the chief

musician to the old gentleman, and who had also composed the following lines

for the occasion –

Hail! Ye victorious heroes,

England’s dauntless saviours, ye

Who on the plains of Waterloo,

Won that glorious victory.

It was a day the world may say,

When Napoleon boldly stood,

Upon the plains of the Waterloo,

There flowed rivulets of blood.

Before the foe he bravely fought,

And when he’d all but won the day,

Would it were night, or Blucher up,

Our hero Wellington did say.

But now behold in effigy,

Him to whom kings such homage paid,

Napoleon mounted on a mule

As though he were on grand parade,

Behold with joy all England sings, Brotton too is up and gay,

The band, the flag, the ball, the dance

Ne’er ceased till the break of day.

1820

By the 1820s, John

Farndale was a Yeoman farmer.

Yeomen farmers owned

land (freehold, leasehold or copyhold).

Their wealth and the size of their landholding varied. The Concise Oxford Dictionary states

that a yeoman was "a person qualified by possessing free land of 40/-

(shillings) annual [feudal] value, and who can serve on juries and vote for

a Knight of the Shire. He is sometimes described

as a small landowner, a farmer of the middle classes". Sir Anthony

Richard Wagner, Garter Principal King of Arms,

wrote that "a Yeoman would not normally have less than 100 acres" (40

hectares) "and in social status is one step down from the Landed gentry,

but above, say, a husbandman". Often it was hard to distinguish

minor landed gentry from the wealthier yeomen, and wealthier husbandmen from

the poorer yeomen.

Yeomen

were often constables of their parish

and many yeomen held the positions of bailiffs for

the High Sheriff or for the shire or hundred.

Other civic duties would include churchwarden,

bridge warden, and other warden duties. It was also common for

a yeoman to be an overseer for his parish. Yeomen, whether working for a

lord, king, shire, knight, district or parish, served in localised or municipal

police forces raised by or led by the landed gentry. Some of these roles,

in particular those of constable and bailiff, were carried down through

families. Yeomen often filled ranging, roaming, surveying, and policing

roles. In districts remoter from landed

gentry and burgesses, yeomen held more official power.

1823

Baines

Directory for 1823 listed the inhabitants of Skelton, with a population of

around 700:

Castle:

John Wharton MP

Curate:

Rev William Close.

Attorney:

Thomas Nixon.

Blacksmiths:

Thos Crater, Robert Robinson, William Young.

Butchers:

William Lawson, Isaac Wilkinson, William wilkinson.

Corn

Millers: Robert Watson, William Wilson

Farmers

and Yeoman: William Adamson, John Appleton, Thomas Clarke, James Cole, James

Colin, William Cooper, Steven Emerson, John Farndale, Robert Gill,

William Hall, Edward Hall, Jackson Hardon, William Hutton, Sarah Johnson,

William Lockwood, John Parnaby, Thomas Rigg, William Sayer, William Sherwood,

John Taylor, William Thompson, Robert Tiplady, William Wilkinson, Richard

Wilson

Grocer

and Drapers: John Appleton, William Dixon, Ralph Lynass, Thomas Shemelds, John

Alater

Flax

dresser: McNaughton D

Joiners:

William Appleton, Leonard Dixon, Mark Carrick, Joseph Middleton

Schoolmasters:

Atkinson M, John Sharp

Shoemakers:

Robert Bell, Luke Lewis, Thomas Lowls, George Lynass, Thomas Steele

Stonemasons:

Thomas Bryan, John Pattinson

Straw hat

makers: Sarah Sarah, Esther Shimelds

Weavers:

Stephen Edelson, Thomas Dawson, John Robinson, Robert Wilson

Land

agent: John andrew

Victuallers:

William Bean at Duke William, William Lawson at Royal George

Woodturner:

James Crusher

Gamekeeper:

Frank Thomas

Plumber

and Glazier: William Gowland

Sadler:

Thomas Taylor

Shopkeeper:

Eliza Wilkinson

Carriers:

Marmaduke Wilson - to Guisborough on Tuesday and Friday, departing 8am and

returned 4pm; Robert Wilkinson to Stockton on Wednesday and Saturday, departing

4am and return 8pm, to Lofthouse on Monday and Thursday departing 9am and

return at 6pm; Letters were brought to Guisborough by coach and thence to

Skelton by daily horse post arriving at 10am and mail taken back at 3pm.

John Farndale, was a yeoman farmer, living at Kilton (record

at Skelton) in 1822 and 1833.

1825

Skelton

Parish Church Warden’s Accounts 1825 -1840: 1825 Assessment for bread and wine at 8s per house and 12d per oxgang; John Farndale @ 1

Oxgang...........5s 6d (Skelton PR).

1826

Skelton Parish Church Warden’s

Accounts 1825 -1840: 1826 Assessment @ 2s

6d per house and 1s 8d per oxgang; John Farndale @ 4 oxgangs.........7s 6d. George

Farndale @ 1/2 oxgang...1s 9d (Skelton PR).

1827

Skelton Parish

Church Warden’s Accounts 1825 -1840: 1827 Assessments @ 2s 6d per house

and 1s 3d per oxgang; John Farndale, 4 oxgangs............7s 6d (Skelton PR).

1828

Skelton Parish Church Warden’s Accounts 1825 -1840:

1828 Assessments @ 1s 6d per house and 1s per oxgang; John Farndale, 4 oxgangs............5s 6d (Skelton PR).

1829

John Farndale of

the Parish of Skelton and

Martha Patton of this

Parish (ie Yarm) were married by licence with the consent this 18th Day of May

in the year 1829 by me John Graves, Curate. This marriage was solemnised

between us, John Farndale and Martha Patton in the presence of Rob Coulson and

Elizabeth Patton.

The Durham County

Advertiser, 23 May 1829: At Yarm, near Stockton, on Monday last, Mr John

Farndale, of Skelton, near Guisborough, to Martha, fourth daugfhter of

Masterman Patton, Esq, of Mount Pleasant, near Yarm.

Skelton

Parish Church Warden’s Accounts 1825 -1840: 1829 Assessments @ 1s 6d per house and 6d per oxgang; John Farndale, 4 oxgangs.............3s

0d (Skelton PR). This was the Year of his

marriage.

1830

Skelton

Parish Church Warden’s Accounts 1825 -1840: 1830 Assessments; 1st class

house 1s; 2nd class house 6d and 3d per oxgang; John Farndale 4 oxgangs/2nd class

house..........................................1s 2d (Skelton

PR).

1831

William Masterman Farndale, born Skelton 24 Mar 1831 (FAR00312) (Skelton PR).

Skelton

Parish Church Warden’s Accounts 1825 -1840: 1831 Assessments; 1st class house 1s; 2nd class house 6d and 3d per oxgang; John Farndale, 4

oxgangs/1st class house..........................................2s 0d (Skelton PR).

1832

Mary Farndale, born Stockton 1832 (FAR00316) (Skelton PR).

Elizabeth Farndale, born Skelton 5 May 1832 (FAR00319) (Skelton PR).

Rates altered

marginally and John Farndale paid 3s in 1832; 4s in 1833; 5s in 1834 and 1835;

4s 6d in 1836; 4s in 1837 and 1838[ 3s in 1839. His name is crossed out in

1840. His wife died in December 1839 and he is next shown in the census as

being in Durham (Baines' Directory).

1833

Teresa Farndale, born Skelton 5 Dec 1833 (FAR00325) (Skelton PR).

1835

Annie Maria Farndale, born Skelton 9 Jun 1835 (FAR00334) (Skelton PR).

1836

John George Farndale, born Skelton 27 Nov 1836 (FAR00337) (Skelton PR).

1838

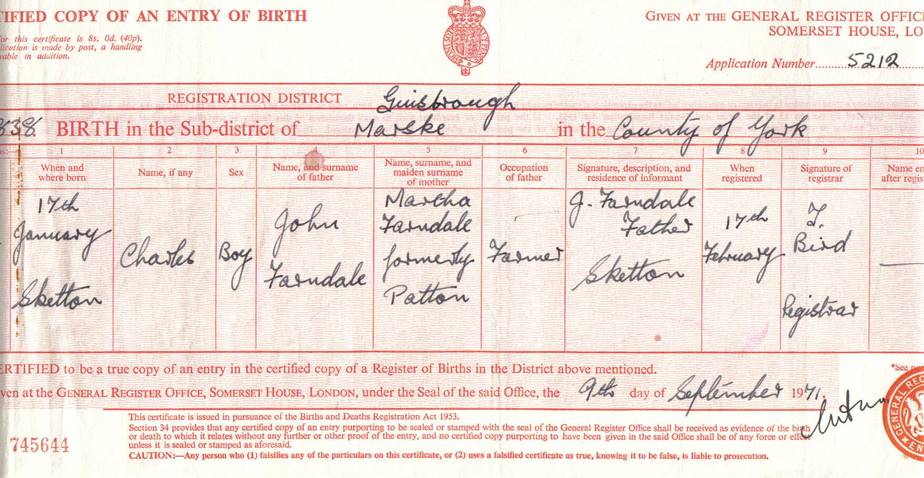

Charles Farndale, born Skelton 27 Feb 1838 (FAR00341) (Skelton PR).

His son, Charles

Farndale's birth certificate in 1838 shows John was then living in Skelton and occupied as a farmer (MC & IGI).

1839

Emma Farndale, baptised Skelton 20 Dec 1839 (FAR00346). (Stockton District Records)

Martha, wife of

John Farndale of Coatham-Stob died aged 39 and was buried on 9 December 1839. Therefore

Emma had been born in 1800. It would appear that

Martha died from childbirth and their daughter Emma then died a few days later

Obituary: ‘Dec 6th. At Coatham-Conyers,

in Stockton Circuit, Matha, the wife of John Farndale. She was truly converted

to God in the twenty sixth year of her age; and from that period she was a

consistent member of the Wesleyan Society. Her death was rather sudden but she

was found ready. Aware of her approaching dissolution she said, ‘This is the

mysterious Providence; but what I know not now, I shall know hereafter.’ Some

of her last words were, ‘Tell my dear husband for his encouragement, that I am

going to Jesus. How necessary it is to live life for God? Oh Lord help me that

I may have strength to leave a clear testimony that I am gone to Jesus.’ It was

enquired, ‘Do you feel Jesus present?’ She replied, ‘Yes,’ and soon fell asleep

in Him.’ MJ. (Methodist magazine, 1840, page

172)

Martha Farndale's death was registered for

Stockton District in the last Quarter of 1839.

However there is also

an entry for May 1846: Farndale, Martha (wife of John Farndale) of Coatham

Parish, Long Newton, Co Duyrham showing probabation for £1,000. It is not clear

why probabtion of her will took so long. (Borthwick

Instituite, Document reference vol.213B, f., Year 1846, Index reference

1845061847060092/1829, Date 1846, MAY)

John did not remarry,

so at the age of 48 he was a widower with a large family.

1840

A newspaper article in

1904 recorded a case which John Farndale raised against two cart racers who caused damage to

John’s gig and harness. The Whitby

Gazette, 11 March 1904 recorded: A RACE IN THE DARK. 25th March,

1840. An old Cleveland newspaper gave the following: Stokesley Petty Sessions,

present Edmund Turton and Robert Hildyard, Esquires. Upon the complaint of John

farndale, of Coatham Conyers, in the county of Durham, against Thomas Hugill,

of Bilsdale, and James S Keen of the same place, for having, on the night of

the 21st January last, at the Township of Stokesley, obstructed the free

passage of a certain highway, by riding a race in the dark, and damaging a gig

and harness driven by J Farndale and James Drummond. Both were fined £2 and

costs.

1841

The 1841 Census, for Coatham Stob, Long Newton listed John

Farndale, 45, a farmer; William Farndale, 10; Mary

Farndale, 9; Teresa Farndale, 8; John Farndale, 5; Charles Farndale, 3;

John Farndale, 15, male servant; Matthew Farndale, male servant, 12; John

Malburn, 25, male servant; Thomas Shirt, 15, male servant; Mary Disson, 24,

housekeeper.

1842

The Yorkshire Gazette, 3 September 1842 advertised:

YARM

A Valuable FARM and

also Productive Ings LAND for Sale

TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION

At the Vane Arms Hotel,

in Stockton, in the county of Durham, on Wednesday, the 14th day of September,

1842, at Three O’clock in the afternoon.

Mr J Baker, Auctioneer,

A very valuable and

highly productive freehold farm, called MOUNT LEVEN, situate at Leven

bridge, in the parish of Yarm, in the County of York, consisting of an

excellent farmhouse and outbuildings and of a Hind’s house, and ONE HUNDRED AND

TWENTY TWO acres of land, of which 54 A, 1 R, 30 P, or thereabouts are

excellent Old Grass, 15 acres or thereabouts turnip and barley soil, and the

remainder good wheat and bean land.

The farm is divided

into 15 convenient sized fields or enclosures, all well watered and fenced, and

is now in the occupations of Mr. John Colbeck, as Tenant to the Trustees of Mr

Masterman Patton, deceased, the late owner thereof.

The property is bounded

by the River Leven on the east, and by the highway leading from Leven bridge to

Yarm on the West and South.

And also, either

together with, or separately from the farm, all those Four Acres of Meadow,

lying in a certain common field, called or known by the name of Yarm Ings, in

the Township or parish of Yarm aforesaid; together with all such right and

title of fishing in the River Tees at or near Yarm as has been usually enjoyed

with the said premises. And also together with a Pew or Stall in the Parish

Church appendent or appurtenant to the said premises, or usually enjoyed

therewith.

The Tenant will send a

person to show the properties; and any further particulars respecting them may

be ascertained of Mr Hugill of Eston; Mr. John Farndale of Coatham Conyers;

of the Auctioneers; or of Messrs Wilson and Faber, Solicitors, Stockton upon

Tyne Tees. Stockton, August 10th, 1842.

The Bankruptcy Notice

in 1851 suggests that althoguh John is referred to as the Auictioneer in this

notice, he was farming at Mount Leven Farm himself.

In 1864 John Farndale

wrote, of about this time, when living in Coatham: How often here on a fine

summer’s eve have I strolled to this most retired and enchanting retreat,

Huntcliff, with my gun, to enjoy a sport of shooting the sea bird darting up

the cliff over-head; an advantageous sport, when an ordinary marksman need not

fail to bag a brace or two. This retreat was part of my Hunley Hall farm, and

is only a short drive from Saltburn-by-the-Sea.

So then he seems to

have farmed at Hunley Hall Farm, which is on the north edge

of Brotton during these years. Ordnance Survey Grid NZ688204.

1847

He seems to have sold Hunley Hall

Farm in 1847. The Yorkshire Gazette, 23

October 1847:

Farm to LET in

Cleveland.

To be entered upon at

the usual Times in the Spring of 1848.

Hunley farm, in the township of

Brotton- in-Cleveland, in the County of York, containing 476 acres of

excellent arable, meadow, and pasture land, with a capital dwellinghouse,

and all requisite outbuildings, and also three cottages in the

village of Brotton, all in the occupation of Mr. John Farndale, or his

under tenants.

Further particulars may

be obtained of Mr George Pearson, land agent, Marske, near Guisborough, who

will direct a person to show the farm, or at the offices of Mr Trevor,

Solicitor, Guisborough.

Guisborough, 12th or

October 1847

1851

The 1851 Census for Danby End, Danby listed John

Farndale, Head (but seemed to be living alone), born 1791 in Brotton, aged 60, an agricultural

labourer.

He was clearly in financial difficulty and in 1851 the Durham County Advertiser, 13 June 1851: DARLINGTON

PETTY SESSION, JUNE 9. Before G J Scurfield, H P Smith, J L Hammkind, and E

Backhouse, Esqrs. … John Farndale, farmer, Long Newton charged by John

Etherington with having discharged him from his service and refusing to pay

the wages due to him, was ordered to pay the sum due and 6s 6d costs.

He became bankrupt and in the London Gazette 1851:

WHEREAS a Petition of John Farndale , formerly of Coatham Stob farm, in

the Parish of Long Newton, in the County of Durham, farmer,

afterwards of Mount Leven farm, in the Parish of Yarm, in the County of

York, farmer, afterwards of Hunley Hall Farm, in the Township of Brotton,

in the same county, farmer, late of the Township of Middlesbrough,

in the said County of York, farmer, and now in lodgings at the House of

James Watson, at Middlesbrough, in the said County of York, labourer and

merchant, an insolvent debtor, having been filed in the County Court

of Durham, at Stockton, and an interim order for protection from process having

been given to the said John farndale, under the provisions of these statutes in

that case made and provided, the said John Farndale is hereby required to

appear before the said court, on the 15th day of April next, at ten in

the forenoon precisely, for his first examination touching his

debts, state, and effects, and to be further dealt with according to the

provisions of the said Statutes; And the choice of the creditors’ assignees is

to take place at the time so appointed. All persons indebted to the said John

Farndale, or that have any of his effects, are not to pay or deliver the same

but to Mr John Edwin Marshall, Clerk at the said Court, at his office, at

Stockton, the Official Assignee of the estate and effects of the said

insolvent.

The entry in 1860

records that he was sent to Durham Prison for a periof of time, for debt.

1854

Within three years after

his bankruptcy, he seems to have started to act as a corn agent. The Darlingtion and Stockton Times, 30 September 1854:

WHEAT SOWING. THE PATENT SANTIARY COMPANY’S ‘CARBON MANURE’ is strongly

recxommended as a Fertilsier. May be had of J FARNDALE, CORN AGENT, STOCKTON.

John’s son, John George

Farndale (FAR00337) wrote home

to his father from the Crimean War.

1855

The Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury, 21 April 1855,

the Newcastle Chronicle, 20 April 1855 and

other media: TURNIP MANURE. THE “PATENT SANITARY COMPANY’S NITO-PHOSPHATED

CARBON” OR BLOOD MANURE, Price Six Guineas per Ton; may be had of … MR J

FARNDALE, Stockton … The above manure contains upwards of 1300 pounds of dried

blood in every ton! and is only half the price of guano. Four or five

cwts per acre is sufficient for turnips.

1856

Only five years after

his bankrupcy, he was back in society, contributing to a

sigmnificant statue project, albeit as an agent.

The Newcastle Journal, 15 March 1856: MONUMENT TO THE

MEMORY OF THE LATE MARQUESS OF LONDONDERRY. At a public meeting of the friends

of the late Most Honourable the Marquess of Londonderry KG, GCB, Lord

Lieutenant of the county of Durham, and of those who respect his memory, held

at the town hall, in the city of Durham, on Thursday the 6th day of March,

1856, to take into consideration the propriety of erecting a public monument

in his honour of that distinguished nobleman. His grace the Duke of

Cleveland KG in the Chair, the following resolutions were unanimously adopted:

moved by F D Johnson Esq of Askley Heads, seconded by the Right Worshipful the

Mayor of Newcastle upon Tyne: (1) That this meeting is of opinion that the

high minded, generous, and benevolent character of the late Marquess of

Londonderry, as a resident nobleman, his indomitable courage, and brilliant

exploits as a soldier, and his bold and successful efforts to develop and extend

the commercial, mining, and maritime resource is of this County, called for

some public momento to hand down his memory to posterity. Moved

by the Worshipful the Mayor of Durham, seconded by Ralph Carr Esq of

Bishopwearmouth. (2) That to accomplish this object, a suitable monument be

erected by subscription, the site and character of which will be determined

at a meeting of the contributors to be hereinafter convened. Moved by R L

Pemberton Esq of Barnes, seconded by Robert White Esq of Seaham. (3) That the

following noblemen and gentlemen be appointed to a committee to carry out the

object of the above resolutions, with power to add to their number, and to form

local committees, viz: His grace the Duke of Cleveland, the Right Honourable,

the Earl of Durham, F D Johnson Esq, William Standish Esq... The following

sums were subscribed at the close of the meeting: The Duke of Cleveland

£200, the Earl of Durham £100, J R Mowbray Esq MP, £25... LAND AGENT AND

TENANTRY ON SOUTH ESTATES.... John Farndale, Long Newton £1 10s 0d...

1859

By April 1859, he was practising as an

insurance agent, operatig in Stockton:

The Durham County Advertiser, 8 April 1859: AGRICULTURAL

PRODUCE AND FARMING STOCK INSURANCE AT 3s 6d AND 4s PER CENT. STATE FIRE

INSURANCE COMPANY. CHIEF OFFICES: NO 32, LUDGATE HILL, AND 3 PALL MALL EAST,

LONDON. Fire officers generally having increased the rates of premium for

insurance on agricultural products and farming stock from 3s 6d per cent,

to 4s 6d percent, without the average clause; The Directors of this Company,

from their experience, finding the rate hitherto charged adequate to the risk,

are now prepared to accept proposals at the following rates viz. With the

average clause, 3s 6d per cent, Without the average clause, 4s per cent. No

expense will attend the transfer of policies from other offices. The company

also undertakes every description of risk at adequate rates. Losses sent

settled promptly and liberally. Agents required, to whom a liberal commission

will be allowed. Applications to be made to the secretary, No 32, Ludgate Hill,

London.... Stockton: Mr J Farndale.

He was also an agent in the

fertiliser/guano trade:

The York Herald, 16 April 1859: TO LANDOWNERS,

FARMERS ANMD OTHERS. GUANO. It is now an established fact that guanos which

are rich in phosphates of lime are more suitable for the growth of root

crops, grass etc than those guanos containing ammonia, which in their turn

are best adapted for the growth of white crops. I give you below the analysis

of a cargo of Korria Mooria Guano, direct from the Islands, which you will find

is very rich in phosphates, and is a valuable manure for turnips and root crops

of every description, and which will be charged at a price exceedingly low

compared with its value as a fertiliser, viz: Phosphate of Lime 61.50%; Organic

Matter 8.25%; Sulphate of Lime: 2.75%; Inorganic matter 15.75%; Moisture 11.75%

- 100%, containing nitrogen 33%, equal to ammonia 40%. Orders taken by Mr

William Pybus, Mr. John Farndale, and others in the guano trade. S

Ingledew, Stockton on Tees, March 11th 1859. Would make a good top dressing for

wheat, oats or barley.

The York Herald, 11 June and 2 July 1859: IMPORTANT

TO FLOCKMASTERS. THOMAS RIGG, Agricultural and Veterinary Chemist, by

Appointment, to HRH the Prince Consort, KG, begs to solicit orders for his

SHEEP DIPPING COMPOSITION, for the destruction of Tick, Lice etc; And for

the prevention of fly, scab etc. Also for his SPECIFIC OR LOTION, FOR SCAB IN

SHEEP OR MANGE IN HORSES OF DOGS. It is only necessary, in giving orders, to

state the numbers of sheep to have the right quantity of each sent. Leicester

House, Great Dover Street, Borough, London. Agents … Farndale - J

Rickaby, Grocer...

1860

In 1860, John Farndale

featured as a witness in his capacity as agent in a trial. The article records

that John Farndale had been sent to Durham prison for debt. John had suffered

bankruptcy, so presumably he went to Durham Prison at that time, although there

is a suggestion in the article that it was in 1859 that he went to Durham

Prison for debt.

The Durham Chronicle and Durham County Advertiser, 9 March

1860: BRAITHWAITE v THE NATIONAL; LIVE STOCKL INSURANCE COMPANY. MR

DAVISON for The plaintiff, Mr. James QC and Mr Fowler for the defendants. On

the part of the plaintiff it was stated that Mr Braithwaite was a farmer and a

butcher residing at Stockton, occupying land in the immediate neighbourhood,

for which he paid £114 a year rent. The plaintiff kept dairy cows, and

for the last three years passed he had insured his stock with the

National Livestock Insurance Company. The date of the policy was the 30th of

June 1859. According to the regulations of the Society the cows were put in

at a certain price, the plaintiff naming the cow in question as of the value of

£16, though in point of fact she was worth £22. By the regulations of the

policy of an insurer is entitled to recover three quarters of the value of

which any animal is entered. The cow in question was called the Newsham cow,

from the name of the farm on which she was bred, and the first appearance of

illness was on the last day, or very nearly the last day, in July. Mr

Braithwaite sent for Mr Eyre, an experienced veterinary surgeon, and he, after

examining it, gave it his opinion that nothing particular was the matter with

the cow. The cow went on feeding and milking until the 3rd of August when it

was observed that she did not chew her cud. After Mr Eyre had seen her, the

plaintiff gave notice to Mr Farndale, the local agent of the insurance

society. Mr Farndale saw her, but he was afterwards sent to Durham prison

for debt, and did not see her afterwards. The cow continued to be attended

by Mr Eyre until the 29th of August when she died. A claim of £12 was

afterwards made upon the Society...

1861

The 1861 Census for 3

Alma Street, Stockton recorded that John Farndale, was married, 63 years old,

and a corn merchant, living with Elizabeth Farndale, his wife, 68, born 1793 in

Yarm. So it seems that he had married Elizabeth Farndale at some

stage.

By 1861, John Farndale was writing. A review of his Guide to Saltburn by the Sea appeared in the Stockton Herald, South Durham and Cleveland Advertiser on

21 Drecember 1861:

REVIEW

A GUIDE TO SALTBURN-BY-THE SEA. BY JOHN FARNDALE.

The writer of this little book of some thirty pages is a

native of Kilton, an adjoining village to Saltburn, and as a great part of

the contents refers to this little village the book should be called “the

history of kilton, near Saltburn by the sea,” of which latter place he had

said little, for what can be said of a place till lately scarcely heard of

beyond its own fields. It is to become a noted place, for he informs his

readers that a hotel is being built to cost £31,000, building sites

are freely offered, and a building society is ready to advance money on

easy terms to any person desirous of speculating in bricks and mortar.

The description he gives of the surrounding country represents some fine

scenery of hill and dale; wood and water, which must tend to make Saltburn by

the Sea attractive to visitors. The writer of the “Guide” makes no pretensions

to authorship, and presents his readers with a sermon at the end, occupying

about a third of the book.

John Farndale first wrote of Saltburn at a time

when it was to evolve from a small fishing village, well known for its

smuggling history, into a modern Victorian seaside resort, with its own reilway

station and grand hotel.

1862

The Stockton

Herald, South Durham and Cleveland Advertiser, 24 October 1862: BISHOPTON LANE STOCKTON. TOBE SOLD, BY PRIVATE

CONTRACT, a Good DWELLING HOUSE Situate in Bishopton Lane, called the LEEDS

HOTEL. Apply to I (sic, recte J) Farndale, No 5, Stamp St, Stockton on

Tees.

Although the reference is to I Farndale, there

were no I Farndales at the time and this is the address of John Farndale (see

below). Bishopton Lane is where Robert

Farndale of the Stockton 2

Line operated his grocery business from. Did John

Farndale of the Kilton 1 Line

work in the same circles as his relatives of the Stockton 2 Line

at this time?

The Stockton Herald, South Durham and Cleveland Advertiser,

24 January 1862: TO LET. With Immediate Possession. A SEVEN ROOMED

HOUSE, 21 ALMA STREET, Stockton-on-Tees. Apply Mr JOHN FARNDALE, 5, Stamp

Street. This same property was advertised by Robert Farndale in 1863, so

presumably John Farndale was sellng it as an agent for his relative, Robert.

1863

The Stockton Herald, South Durham and Cleveland Advertiser,

26 June and 3 July 1863: FOR SALE, A PASSAGE WARRANT TO AUSTRALIA AT

HALF PRICE. Open until July, 1863, for a single eligible young man. Apply (post

paid) to JOHN FARNDALE, 20, Park row, Stockton-on-Tees.

The Stockton Herald, South Durham and

Cleveland Advertiser, 4 September 1863:

REVIEW

A GUIDE TO SALTBURN-BY-THE SEA. BY JOHN FARNDALE.

This little book has now reached a second edition,

which we think rather extraordinary. The author makes no pretensions to

a literary production, but has compiled an amusing book, and given a

description of Saltburn and the surrounding country in his quaint manner.

Having been born on a farm in the neighbourhood, and lived to be an old man, he

has called up memories of the departed who had figured their little day unseen

and unknown beyond the village or farm. The book contains a map of

Saltburn, and the country round, with a plan of the intended town, and a

view of Zetland Hotel. To most our of our readers in this in the distance, Saltburn

by the Sea is a name almost unknown. The Stockton and Darlington railway

company have made a line from Redcar to an out of the way place which

possesses some extraordinary natural appearances and fine sea beach. Here they

have erected a very spacious hotel to the east of some £30,000. A plan of

the town has been laid out, and several houses have been erected, with

the intention of making the place a summer resort for sea bathers. The author

of the guide has described the roads around the intended town's drives for

visitors, and has given matters matter which will afford amusement to the

readers. At present Saltburn contains but few buildings, but every

inducement is offered to encourage persons to build. The place is very is a

very pleasant one and may someday become a town when this little book will be

in demand.

The Whitby Gazette, 21 November 1863: TO OWNERS OF

LAND CONTAINING IRONSTONE. ANY party having ironstone to dispose of in

the neighbourhood of a railway or the sea coast, may hear of a customer by

application to a B, Care of Mr Farndale, Bishopton Lane, Stockton on Tees.

November 16th 1863.

1864

By 1864, John was acknowledged as an author. John Farndale wrote a

fourth edition to his small guidebook about Saltburn by the Sea in 1864 noting

that Saltburn was but an `embryo`, but he complimented the Improvement Company,

noting that they already made substantial progress as “already the hand of

improvement has effected (sic) a revolution at this place”. The Stockton Herald, South Durham and Cleveland Advertiser, 5

August and 16 September 1864: NOW READY – FOURTH EDITION. THE

GUIDE TO THE CLEVELAND DISTRICT and SALTBURN BY THE SEA, enlarged and with

Additional Rambles, and an interesting brief supplement on the science of

the animal, vegetable, and mineral Kingdom in the Cleveland district. May

be had of all booksellers, Messrs Webster and Smith, High Street; And the

author, John Farndale, 20 Park Row, Stockton.

In his book on

Saltburn, in 1864, he advertised: JOHN FARNDALE. CORN MERCHANT, COMMISSION

AGENT, AND AGENT. To the London General Plate Glass Assurance Company, capital

£10,000. Yorkshire Fire and Life Assurance Company, capital £500,000. Norfolk

Farmers Livestock Assurance Company, capital £500,000. And Accidental Death

Assurance Company, capital £100,000. 20 Park Row, Stockton on Tees.

So by the 1860s when he

was writing his books, as recorded in the 1871 census, he was an insurance

agent and corn merchant.

In

1865 there was an extraordinary squabble between two authors, John Farndale,

and a man named William White Collins Seymour. William White Collins Seymour accused

John of writing a defamatory work about him (possibly ‘Goliah is dead’),

advertised by a pamphlet “Shortly will be published the Life of the

notorious Seymour”, and assaulted him in Stockton.

In the Leeds Times, 15 April 1865:

A SQUABBLE BETWEEN RIVAL AUTHORS. At the Stockton Police

Court, on Thursday, William W C Seymour, quack doctor, of Middlesbrough,

author of “Who’s Who?”, “The Gridiron”, and “other “popular works” was charged

with an assault on John Farndale, author of “A Guide to Saltburn by the

Sea” and an unpublished work, to be designated “Goliah is Dead”.

The plaintiff, in narrating his complaint, said that

defendant, a person to whom he had never spoke in his life, and with

whom he had no connection whatever, assailed him on the previous day in the

Market place. He used the most abusive language to him, charged him

with being the author of a certain handbill entitled “Shortly will be

published, the Life of the notorious Seymour”, and alleged also that he had

been actively employed in circulating copies of that bill. Exasperated by the

language which defendant had used he, (plaintiff) did call him a “wicked

brute” when he (defandant) lifted his foot and kicked him behind

(Laughter). The kick was a severe one; in fact it had inflicted a wound (Great

Laughter). He had undergone a medical examination that morning, and intended to

be examined again (Roars of laughter).

Defendant then addressed the magistrates at considerable

length, premising that the charge was of such a paltry description that

he had not thought it necessary to avail himself of professional assistance.

He then proceeded to say that he had at one time been brought before the

magistrates for using the language of an eminent statesman; the next day for

reading Thomas Hood’s lyrics; a third time for calling a man a cobbler; and

that day for inflicting a serious injury upon that eminent and

distinguished, that moral and pious man, John Farndale. He then proceeded

to enumerate his own publications – “Who’s Who” &c; stated that

complainant, who was John Dunning’s protégé, had charged him with giving 2s for

a dishonoured bill of a Middlesbrough magistrate; had circulated placards professing

to give his (defendant’s) history in connection with certain electioneering

matters in the county of Warwick, charging him with seducing a

publican’s daughter, with sending his son away to die in a foreign land,

&c. So far as electioneering matters were concerned, everything was fair,

from kissing a man’s wife to knocking him down; but as regards the other

charges they were totally unfounded, and while what he wrote was public

property, parties who commented upon it must adhere to the truth. As

regarded the assault, complainant first laid his hands upon his

shoulders and called him a blackguard, and he then raised his foot, but did

not strike complainant. Complainant called him a liar, and that was a

monosylable he would not submit to from any man in the country; neither would

he suffer those who were dear to him to be held up to public ridicule by a

contemptible nondescript like that.

Complainant “wished to say a dozen lines” but was told the

case was closed.

The magistrates, by a majority, decided to inflict a penalty

of 5s and 11s costs, the Mayor observing that but for the provocation the

penalty would have been heavier.

Defendant: I bow to the bench. Such things generally prove a

very excellent investment and are returned a hundredfold. Having paid his fine,

he left the court, observing that a great statesman had said that there were

only two ways of dealing with a rogue – one was a whip and the other something

else. The Mayor said that might be so; but it should not be adopted if other

means could be used.

The Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 8 April 1865:

EXTRAORDINARY ASSAULT

CASE AT STOCKTON. Yesterday, at Stockton, before J Byers, Esq. (mayor), W

Richardson, P Romyn and R Craggs, Esqs., Mr W W C Seymour, a gentleman of

considerable celebrity, was charged by Mr John Farndale, of Stockton, with

assault.

The plaintiff, in

narrating his complaint said that the defendant, a person whom he had never

spoke to in his life, and with whom he had no connection whatever, assailed him

on the previous day in the Market Place.

He used the most abusive language to him, charged him with being the

author of a certain handbill entitled “Shortly will be published the Life of

the Notorious Seymour”; alleged also that he had been actively employed in

circulating copies of that bill. Exasperated by the language which the defendant

had used he (the plaintiff) did call him a “wicked brute”, when he (defendant)

lifted his foot and kicked him behind. (Laughter). Had been labouring in great

pain ever since and was almost unable to sit in consequence. Never gave the man

any offence. To the bench: The kick was a severe one. In fact it had inflicted

a wound. (Great laughter). He had undergone a medical examination that morning,

and intended to be examined again. (Roars of laughter). Defendant charged him

with writing some kind of circular but he (the plaintiff) knew nothing about

it. The assault took place at the Shambles ed.

The plaintiff was

further subjected to a severe examination by the defendant, the cross fire kept

up between the two creating considerable merriment in court.

Two witnesses, William

Artian and George M’Naster, were called as witnesses by the plaintiff, and from

their evidence it appeared that an assault had been committed.

Defendant, in

addressing the Bench, enumerated several grievances, mentioning inter alia the

fact that he (plaintiff) had called him a liar, a monosyllable he would not

take from any man in the country, and he held that the assault, not nearly so

severe as had been alleged, was in some sort excusable.

The Bench, after consulting for

a short time, said they were of the opinion that the assault had been

committed, although doubtless there had been some provocation,

therefore they fined defendant 5s and costs.

John Farndale may have been the author of an

unpublished publication called Goliah is Dead.

William WC Collins was

the author of "The Evil Genius of Middlesbrough or Town Council

Decadence. An epistle to Gabey Tyke" and Who’s Who. How is

Middlesbrough Ruled and Governed, 1864 and The Middlesbrough Pillory or

Tommy Tommyticket’s Disqualification for a magistrate with a satirical epistle

to King Randolph on Brute Force, 1965.

Perhaps as a fellow

authors in the same area at the same time, the two struck up a rivalry.

John Farndale was a

witness to the Will of his sister, Anna Phillips

(nee Farndale), in which he was recorded as a Corn Merchant: The Will of

Anna Phillips late of Stokesley in the county of York deceased who died 22

November 1867 at Stokesley aforesaid was proved at York by the oath of John

Farndale of Stockton upon Tees in the County of Durham Corn Merchant the sole

Executor.

1868

By 1868, John Farndale was in business with a man

named Burlinson. The Richmond and Ripon Chronicle, 17 October

1868: GYPSUM MANURE. GYPSUM or SULPHATE of LIME (Pure, not a made

Gypsum), 30s per Ton. In 2 cwt Bags, charged 6d each if not returned.

Manufactured and Sold by BURLINSON and FARNDALE, CLEVELAND WORKS,

SOUTH STOCKTON ON TEES. Carriage paid on 10 Tons Orders and upwards to any

Station within 50 miles, on receipt of Cheque with order direct to the Works.

The Darlington & Richmond Herald, 9 May 1868: STOCKTON

ON TEES. TO BE SOLD BY PUBLIC AUCTION. At the Talbot Hotel, in Stockton, in the

county of Durham, on Thursday, the 21st May, 1868, at six o’clock in the

Evening, in the following or such other lots as may be agreed upon at the time

of sale, and subject to such conditions as shall then be produced. Message

Henderson and Hornby, Auctioneers.... Lot 2. All that copyhold DWELLING HOUSE,

situate and being No 5, in Queen Street, Stockton, with the outbuildings and

appurtenances, now in the occupation of Mr John Farndale....

1869

The Richmond & Ripon Chronicle, 30 January 1869: GYPSUM

MANURE OR SULPHATE OF LIME. Messrs BURLINSON AND FARNDALE, , SOUTH

STOCKTON-ON-TEES, ARE PREPARED to SUPPLY this Valuable MANURE, recommended by

some of the most scientific authorities for increasing crops, and in fixing the

qualities of farmyard manures; also as a deodoriser in preventing disease among

cattle, its benefits are incalculable. Testimonials and references, from those

who have had practical experience of its value, may be had on application.

Price at the works, 30s, per ton, net cash. Bags charged for, if not retured.

The Northern Weekly Gazette, 24 December 1869: IMPORTANT

TO BUILDERS, CONTRACTORS AND OTHERS. PORTLAND and LIGHT ROMAN CEMENTS and

PLASTER OF PARIS are manufactured of first rate and warranted quality, at the

CLEVELAND CEMENT AND PLASTER WORKS, SOUTH STOCKTON BY BURLINSON AND FARNDALE.

Also dealers in LATHES (Patent & Rivers), CEMENT and MARBLE CHIMNEY PIECES

(of every design and size) of first class finish, at most reasonable prices.

Goods of their manufacture. Carriage paid in two ton lots. Price lists and

terms on application. Sample orders promptly executed.

1870

In 1870 John wrote: The History of the Ancient Hamlet of

Kilton-in-Cleveland, printed by W Rapp,

Dundas Street, Saltburn 1870; The History

of Kilton dedicated to the Reverend William Jolley , Returning Immigrant, by

John Farndale, The Emigrants Return, printed by Burnett and Hood, Exchange

Offices, Middlesborough, 1870 and a further edition of A

Guide to Saltburn by Sea by John Farndale - Farndale, John, A Guide

To Saltburn By The Sea and the Surrounding District With Remarks on Its

Picturesque Scenery, (Darlington: Hird, 1864)

A text, Impact

of Agricultural Change on the Rural Community - a case study of Kilton circa

1770-1870, Janet Dowey includes much about John Farndale and his

writings and there are extracts from this at John Farndale’s Writings

page and at the Klton page.

John Farndale 1791 to

1879

John and his business partner, Burlinson, seem to

have been in financial difficulty again by 1870. A very large number of

similar advertisements appeared in newspapers in 1869 and 1870. The Northern Weekly Gazette, 21 January 1870: SALES

BY AUCTION. SOUTH STOCKTON. TO FARMERS, MANURE MANUFACTURERS AND OTHERS. MESSRS

PYBUS AND SON will SELL BY AUCTION under a distress for rent, on the premises

lately occupied by Messrs Burlinson, Farndale and Co, South Stockton, on

Wednesday, January 26, 1870, about 50 tons of gypsum, in lots to suit

purchases. Sale to commence at three o’clock in the afternoon prompt.

A Report of the

Stockton Board of Health in the Northern Weekly

Gazette on 29 July 1870: Gentlemen, I beg to report that the

levelling, paving, flagging, and channelling of George Street, King Street, and

Thorpe Street have been completed, and I lay before you the amount of

apportionment incurred by the Board amongst the several owners off premises

fronting, adjoining, or abutting there on, as under, viz... Thorpe Street …John

Farndale £3 8s 8 ¾ d.

The Daily Gazette for Middelesbrough, 24 October 1870:

NON PAYMENT OF RENTS. … Messrs Burlinson and Farndale did not answer to a

summons charging them with non payment of poor rate amounting £2 10s 10d.

An order for the amount and costs was made, in default distress….

1871

By 1871 John Farndale was continuing to work as an

insurance broker, and was living on his own in Stokesley.

The 1871 Census for 49 Back Lane, Stokesley

listed John Farndale, a widower, aged 79, insurance agent living with

Joseph Blackburn, his grandson, aged 9. Joseph Blackburn was the son of his

daughter Elizabeth nee Farndale (FAR00319) and Joseph

Doutwaite Blackburn.

1873

The Northern Echo, 21 February 1873: Back Lane,

Stokelsely. MR WATSON, of Guisborough, is instructed by Mr John

Farndale, who is leaving the place to sell by auction, on Saturday,

February 22nd, 1873, the following modern household furniture and effects:

Eight days Clock in Mahogany case, Half chest of Mahogany Drawers, four

Mahogany Chairs and one Arm ditto, pianoforte, Mahogany Desk and Drawers,

Centre Table, 2 Oak Tables, Weather Glass, American Clock, four Kitchen Chairs

and cushions, Secretaire and Bookcase, Camp Bedstead and mattress, Iron

Bedstead and mattresses, Iron bedstead and mattress, Prime feather Bed, bolster

and pillows, blankets, sheets, counterpanes, oak Washstand and Chamber service,

Carpets, Druggets, Ma’s, Pier Glass, Dressing glasses, Stair carpets, and Brass

rods, fenders and fire irons, several engravings, Rollin’s Ancient History,

Wesley’s works, Fletchers works, Benson's commentary on the scriptures,

Josephus on the History of the Jews, and a variety of other valuable works,

Kitchen table with bottle rack attached, tea and breakfast services, plates and

dishes, scales and weights, small anvil, garden tools, and a quantity of sacks

and bags. The house to be let, and may be viewed on application to Mr F

B Martin, and possession given immediately after the sale. Sale punctually at

one o’clock. Cleveland sale offices, Guisborough, Redcar, and Stokesley.

1874

On his 84th birthday he

wrote his memoirs imn 1874. He stated that he was in good health.

1877

The Northern Echo, Monday14 May 1877: A STOCKTON

WIFE BEATER. On Saturday James Moss, Taylor, was brought up charged with

assaulting his wife, Elizabeth, on the preceding day. Prosecutrix stated that

her husband arrived home about three o’clock in the afternoon in a state of

drunkenness, and after abusing her followed her into a neighbour’s house on the

gallery, where he assaulted her. Prisoner was further charged with being drunk

and disorderly at the magistrate clerks office at the same time. Mr Jennings,

deputy magistrates clerk, deposed to the prisoner’s wife entering the office

for protection followed by her husband, who made a great disturbance and

attracted a crowd of people. Mr Farndale forcibly ejected him, when he

pulled his coat off and wanted to fight. He was very drunk at the time. For

assaulting his wife he was fined 10s 6d and 9s 6d costs, or in default of

payment a month imprisonment; And for the second charge fined 5S and 4S6D

costs, or seven days imprisonment.

1878

John Farndale aged

86 years, Gentleman, died of senile debility at Kilton. Charles

Farndale, his son was present at the death 28 January 1878. (Brotton PR) He was buried at Brotton on 31

January 1878. The York Herald, 1 February 1878:

DEATHS. FARNDALE – January 28th, at Kilton, aged 86 years, Mr

John Farndale.

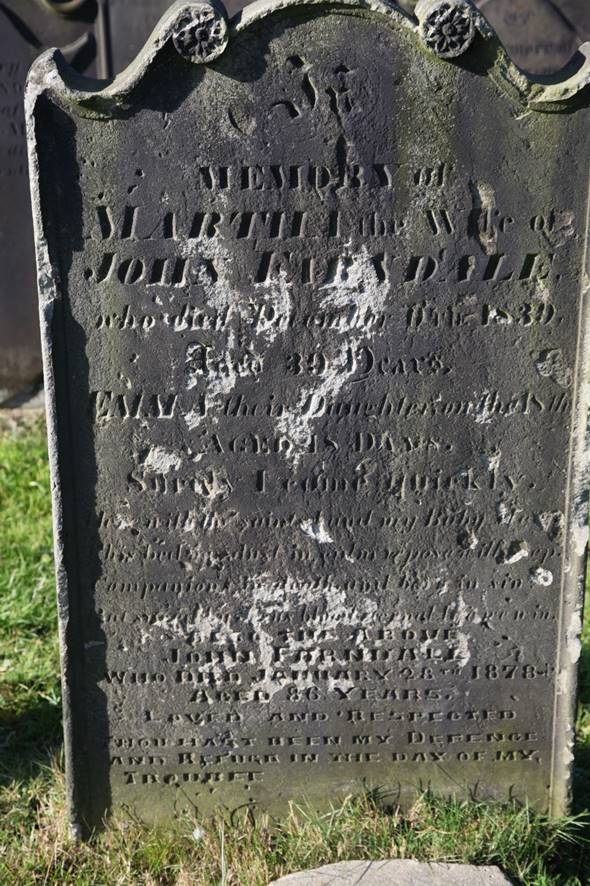

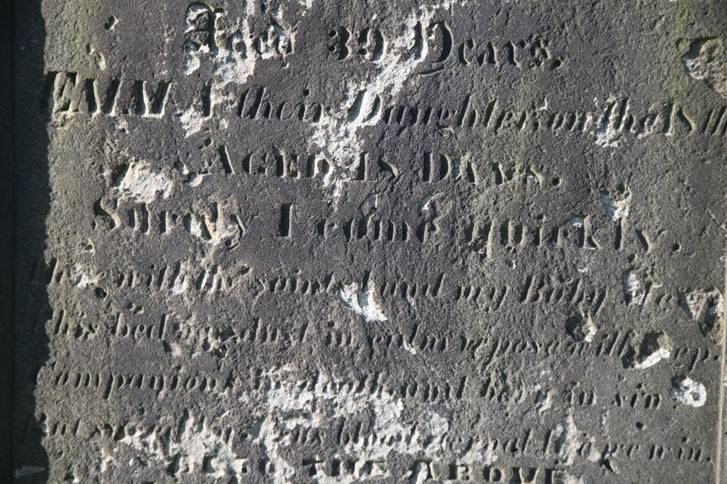

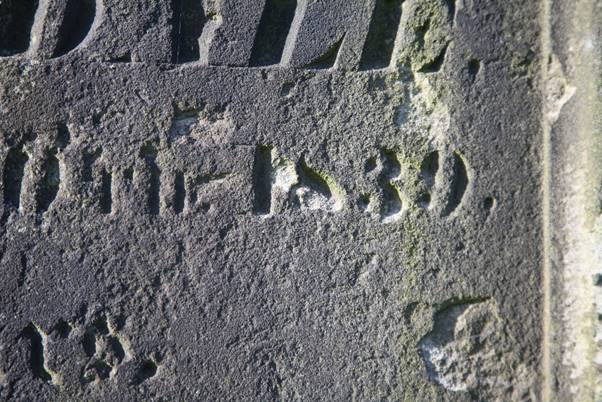

His gravestone Old Brotton

Churchyard: In memory of Martha the wife of John Farndale who died 6th

December 1839 aged 39 years. Emma their daughter on the 18th aged 18 days.

Verse. [unreadable]. Also the

above John Farndale who died 28th January 1878 aged 86 years, loved and

respected. Thou hast been my Defence and Refuge in the Days of my thoughts.

|

|