|

Charles

Farndale of Kilton Lodge |

Kilton The

heart of the Farndale family A Guide to the History of Kilton |

John

Farndale who wrote about Kilton |

The History of

Kilton is in three Chapters:

1.

The

Geography of Kilton. An

orientation section which explores the geography and key features of Kilton.

2.

The

History of Kilton. A

study of the history of Kilton through the Middle Ages, through to the

seventeenth century, Victorian times and the early twentieth century.

3.

The

Farndales of Kilton.

This section focuses on the close association between the Farndale family and

Kilton between about 1705 and 1940.

For ease of

navigation:

Chapter headings and sub

headings are in brown.

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

Chapter 1 - The Geography

of Kilton

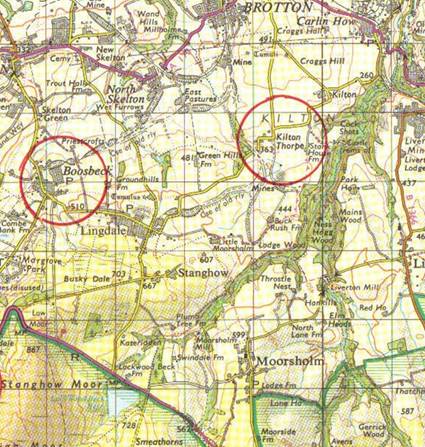

1.1 Kilton

Kilton is a

village in the borough of Redcar and Cleveland in the County of North

Yorkshire. Once a thriving settlement, Kilton today comprises mostly farmland,

with a small settlement at Kilton Thorpe. To the east is the narrow ravine of

the Kilton Beck Valley through which the Kilton Beck flows towards the sea at

Skinningrove. In the midst of the heavily wooded area

of that valley lie the ruins of Kilton Castle. About 2km to the north is the

town of Brotton and Carlin How and Craggs Farm. To the south of Kilton

Thorpe. There are the scrag heaps and disused buildings of the industrial graveland of the old ironstone mines.

From White’s

History, Gazetteer and Directory for 1840 for Yorkshire, East and West Ridings:

KILTON, a small neat village, 6 miles NE by E of

Guisborough, has in its township 80 inhabitants and 1,510 acres of land, all

the property and lordship of John Wharton Esq and formerly belonging to the

ancient family of Thweng, who had a castle here, of

which some traces still remain. Directory: Jph

Newbegin, vict; Thos Robson, miller; and Matthew and

Martin Farndale, George Jennings, George Moore, Thomas Raw & Joseph

Thompson, farmers.

In The

History of Kilton, With a Sketch of the Neighbouring Villages, By the Returned

Emigrant, Dedicated to the Rev William Jolley, Toronto, Canada, America,

Middlesbrough, Burnett & Hood, “Exchange” Printing Offices, 1870, Redcar

Cleveland Library Book No: R000040114 Classification: 942.854, Book No:

R000040114, John Farndale

wrote:

“No place can equal Kilton for

loveliness”, standing as it does, in the midst of sylvan scenery, beautiful

landscape and woodland scenery, and what a perfume of sweet fragrance from wild flowers,

particularly the primrose-acres that would grace any gentleman’s pleasure

ground for beauty and for loveliness. Kilton, as it is situated, is fitted only

for a prince.

We believe Kilton had the pre-eminence

of many of its neighbouring villages. We knew no poachers, no cockfighters,

no drunkards, or swearers. Kilton people were church-going people, yet, on a

Sunday afternoon, what hosts of young men and young women mustered for play,

their song was:

There is little Kilton, lies under yon

hill,

Lasses anew lad, come when you will;

They’re witty, they’re pretty, they’re

handsomely bound,

A lo! for the lasses in Kilton town

In A Guide

to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding District, With remarks on its

picturesque scenery, Fifth Edition, Dedicated to John Thomas Wharton Esq of

Skelton, By John

Farndale. Late of Skelton Castle Farm, Darlington, Printed by Charles W

Hird, 1864, John

Farndale wrote:

Kilton stands unrivalled for its

antiquity, and its

beautiful scenery cannot be excelled. The brightest and fairest scenes

in Italy cannot be compared to the lovely prospects which Nature displays in

this secluded part of Cleveland. This place stands on a ridge of rich loomy land, with Huntcliffe on

the north, known to all sea-men. On the east is

the beautiful bay of Skinningrove and the hall of AC Maynard Esq, formerly the

residence of F Easterby Esq. Skinnngrove

was once a noted place for smuggling. On the north west

is Old Saltburn which was formerly considered the King of the Smuggling

World. Near which is New Saltburn, about to become one of the most

fashionable sea bathing places on the eastern coast, thanks to the enterprising

gentlemen who conduct the railway operations in this neighbourhood, and who are

the public’s benefactors, in a commercial, social point of view, and are

indeed, in every sense of the word, the friends of the people.

In his

memoires he described Kilton as "of great interest with a great hall, stable,

plantation and ancient stronghold in ruins (Kilton Castle)". "It

is still a small place" he says and he describes how many have left it

and made their name.

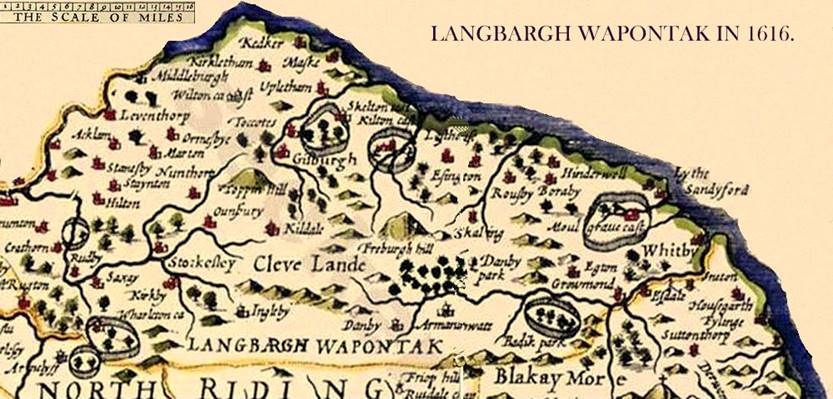

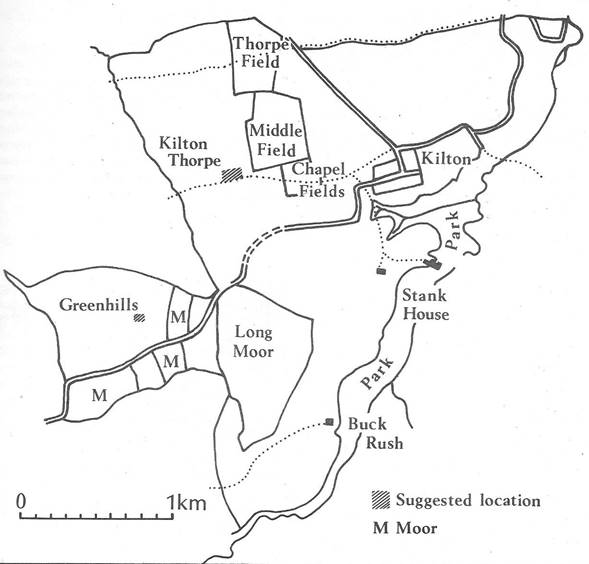

1616

Kilton: A

Survey of a Moorland Fringe Township, by Robin Daniels, 1990, includes the

following reconstruction of the medieval landscape of Kilton:

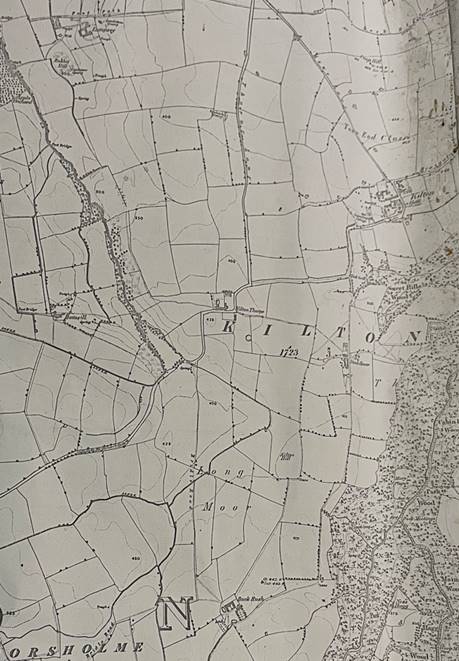

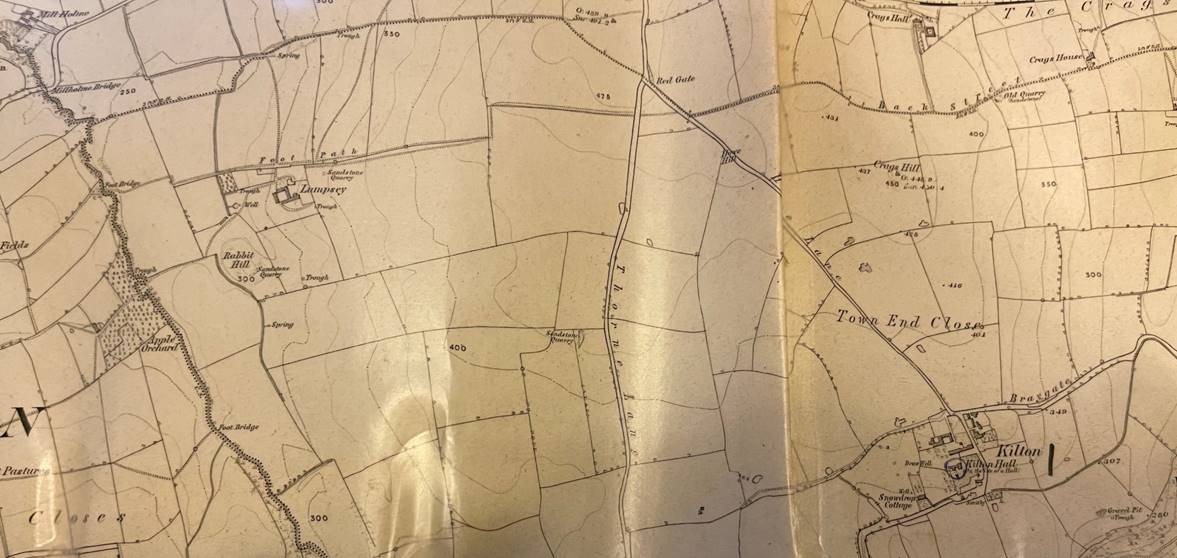

1767

The following are

extracts from the estate plan of 1767 (“Joseph Tullie’s Estate Plan”),

with many thanks to Tony Nicholson for his help and annotations.:

The Village is

highlighted by a red square

Kilton

Hall is shown at the end olf the village street

Five houses on each

side of the street, as described in John

Farndale’s works.

Other houses highlighted yellow.

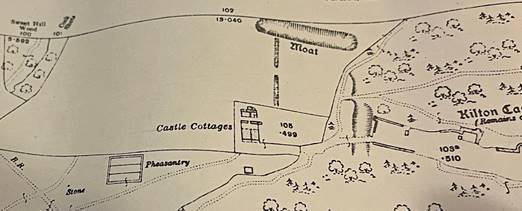

Kilton: A

Survey of a Moorland Fringe Township, by Robin Daniels, 1990, redrew the Kilton

Township Estate Plan of 1767 onto the 1856 OS 6 inch map:

The 1767 map shows a

landscape which, while containing much of the mediaeval past, had undertaken a

dramatic transformation. Enclosure of the mediaeval fields had taken place and

probably partly as a result of this the number of farmsteads had increased from

perhaps five in the mediaeval period to 8 in 1767. An Estate village had been

established at Kilton, a hunting lodge at Buck Rush, and a number of new

buildings had been built. In addition, two new roads had been constructed, the

first linking Brotton to Kilton Thorpe and cutting through the enclosure

boundaries of Middlefield, and the second running from Kilton Lane to the new

farm at Stank House, which continued on to the Lodge and Buck Rush. The last of

these roads survives much as built and is a fine example of a broad 18th

century road which contrasts markedly with its mediaeval predecessors.

The Kilton of 1767 was

very different from medieval Kilton. While some of the medieval properties

either side of Kilton Lane had buildings on them, the village had been moved to

the north. A finer state village had been created, with a street and green and

two rows of cottages facing each other across it. A post mill was shown at the

western end of the South row.

The street and green

were not a thoroughfare, and only gave access to the hall and there is no trace

either on the ground or maps of there ever having been a thoroughfare. The new

two row settlement cut existing property boundaries.

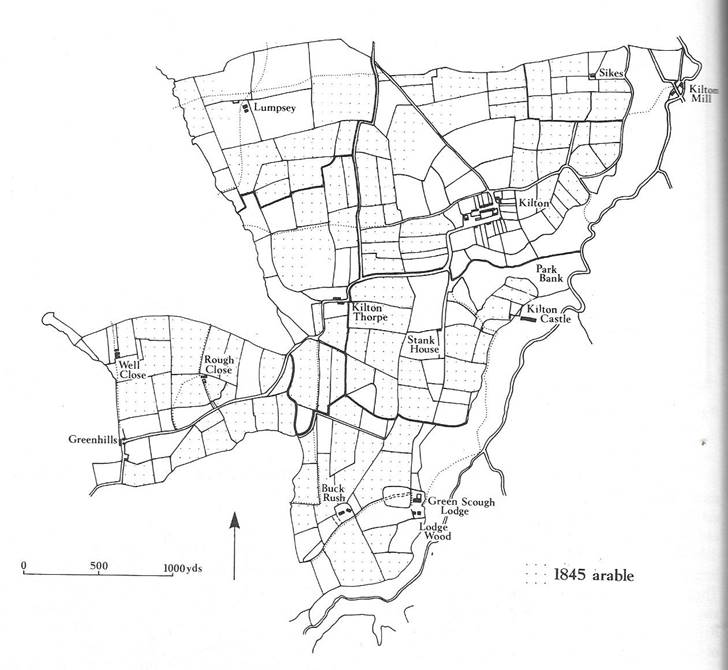

1845

By 1845 this village was

in decay. There was no indication of the post mill and new sets of buildings

had begun to develop to the east of the road. The tithe map of 1845 shows the

estate village in decay and it is obvious that the reorganised landscape was

not being sustained. The lodge had disappeared as had the buildings at the

earthworks at Stank House and two of the farms within the western arm of the

Township. The Township was reverting to an intensity of settlement very similar

to that evidenced in the medieval. Land use in 1845 was predominantly arable,

as it had been in the medieval period, but there seems to have been more

pasture then at the height of medieval cultivation.

1853

Kilton 1853 showing

Kilton, Lumpsey (top left) and Buck Rush (bottom centre)

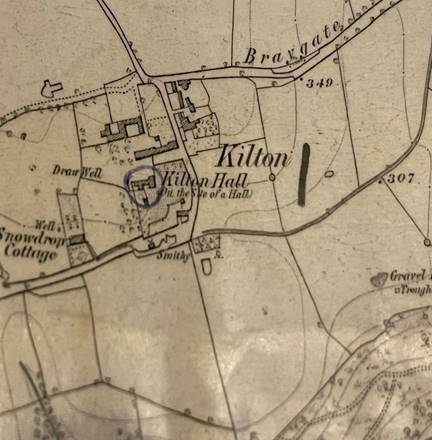

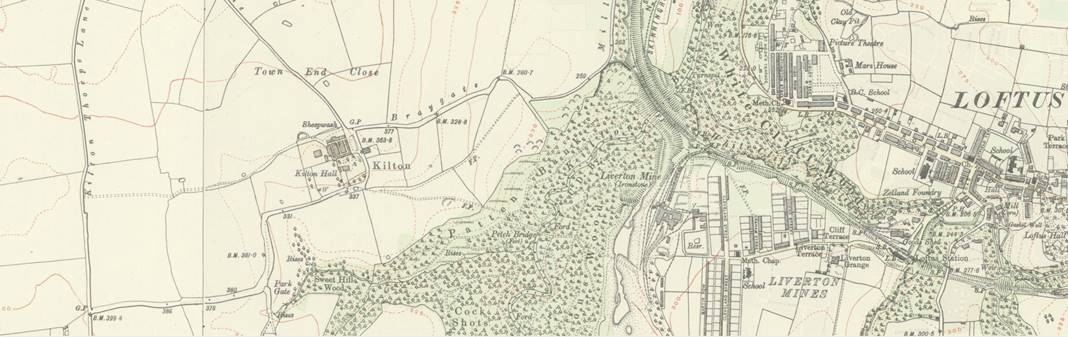

1856

The 1856 map shows this

decay continuing, a courtyard farm under development in the north row and the

present kilton Hall Farm had been built to the South of the village, probably

indicating the absence of the landowner and the establishment of a substantial

tenant farm.

The 1856 Map of Kilton,

surveyed in 1853:

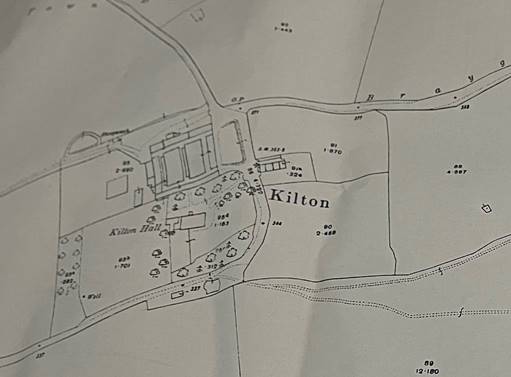

1888

Kilton in

1888:

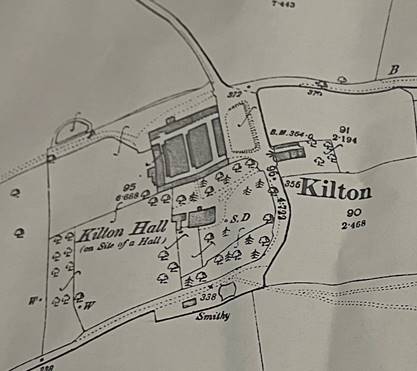

1893

Kilton in

1893:

Substantial

changes occurred at Kilton in the late nineteenth century. The estate village

was demolished and a range of brick built farm

buildings were constructed over the site of the village. These buildings served

Kilton Hall Farm, which was the only domestic dwelling to the west of the road.

On the opposite side of the road, a row of estate cottages were

built in the same architectural style as the outbuildings.

Following the

failure of the reorganisation of the landscape in the eighteenth century, a

consolidation took place in the nineteenth century, perhaps between 1870 and

1893 and certainly between 1856 and 1893. The attempt to foster a village at

Kilton was abandoned and a single, substantial farm was established. To the

west, Greenhills Farm moved from its position on the western boundary into the

centre of its area. Elsewhere within the Township farmhouses were renewed and a

state cottages built. The financing of these measures

may well have been derived from the ironstone mines, but there is little else

to indicate the impact of industrialization on the landscape. The estate and

Township were not dependent on industry and so the landscape of Kilton survived

the closing of the mines extremely well and the Township today is primarily an

agricultural landscape, almost completely given over to crop production.

There are a

few areas of grassland which coincide with the original medieval earth works.

The area now

consists of individual farms with the exception of the

small hamlet at Kilton Thorpe, the school of which has since been converted

into a private dwelling. The estate workers’ cottages at Kilton and adjacent to

the castle remained in use by the estate. The steep sided valley of Kilton Beck

became heavily wooded. There was some small scale

quarrying in the valley, but this was unobtrusive.

The ironstone

mining finished in the 1960s and has left behind the great spoil heap at Kilton

mines. The earthworks of the railways, built to service the mines, still

survive along with a solitary signal post which is set to halt.

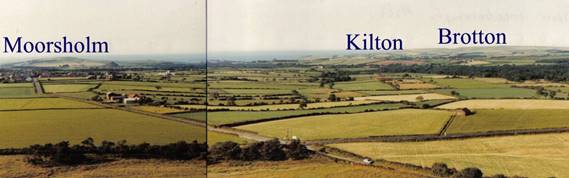

Modern Kilton:

Countryside at Kilton in 1980

and in 2016

1.2 Kilton Hall

A

Guide to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding District, With remarks on its

picturesque scenery, Fifth Edition, Dedicated to John Thomas Wharton Esq of

Skelton, By John

Farndale. Late of Skelton Castle Farm, Darlington, Printed by Charles W

Hird, 1864:

Kilton Hall

as in ages past

Most

beautiful to all around,

Ah! ruthless

hand that gave command,

And now no

trace of it is found.

Kilton formerly belonged to the Twings and Lumleys, who were

lords of the manor. Dr Waugh, Dean of Carlisle, and Miss Waugh, into whose

hands the estate came, sold it to Mrs Wharton, and this lady made a present of

it to the late J Wharton, Esq., of Skelton Castle, MP

for Beverley, a gentleman of memorable name. Here was built a neat hall, much

admired, and when the sun early n the morning cast

its beams upon it and lit its vast windows with Nature’s glory, it was a sight

to affect the heart and raise the thoughts to the Great Source of all beauty

and splendour, both in nature and grace. A spirit of jealousy led to this fine

structure being pulled down, and now not one stone on another remains to tell

where it once stood, except stables, granaries and

coach houses, yet in good preservation. In this township too stands an old

Norman Castle. Few ruins in England can vie this venerable relic of Norman

architecture. There is also a fortress here, which in the olden times must have

been impregnable. This baronial fortress was no doubt the most powerful one in

Cleveland, and in the days of cross bows, broad swords, and battle axes it

would be quite secure. But when Cromwell, that inveterate foe to all Roman

edifices, came near, he heard and was led by the bell at noon, to the opposite

mount, levelled his destructive cannon against this structure, and brought it

to the ground.

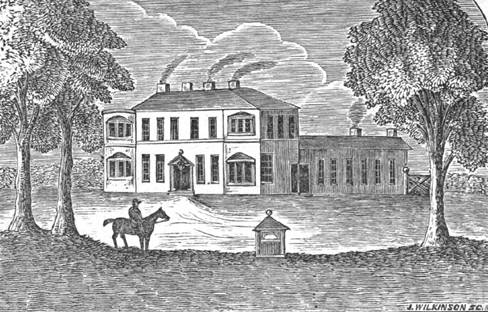

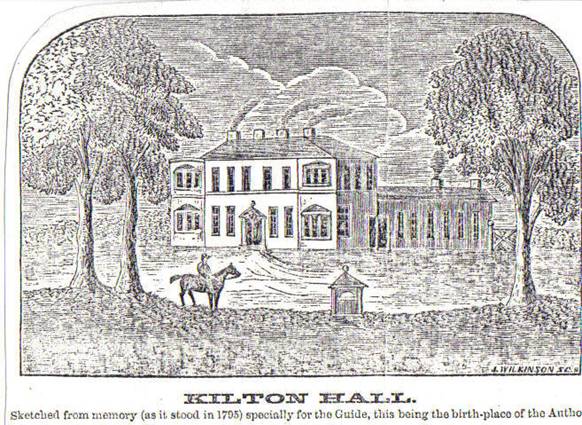

Kilton Hall, Sketched

from memory (as it stood in 1795) specially for the Guide, this being the

birthplace of the Author.

… Kilton Hall was a very neat building, with stables,

coach houses, lawns and plantations, and the old castle adjoining had a

fine bowling green and excellent fish ponds, fed by a

rivulet running through a field close by, and which was in a good state of

preservation until it was lately filled up and ploughed. Contiguous to the old

castle walls there was a fine orchard, which I had the management of about

fifty years ago. But this has nearly gone into decay – the towering pear and

other fruit trees have become leafless and dead, and withered like an old man

ripe from the grave. Such are the changes which a few years make. Thus, it is

with inanimate things, so it is with us. We must all fade as a flower, we must

all die, for all flesh is grass. “The grass withereth,

the flower fadeth, but the word of the Lord endureth for ever”.

Here, let me not forget to notice that,

in this enchanting park, rich preserves of game of all kinds, especially that

most beautiful bird the pheasant, are numerous, and almost all other game. I

have seen rise out from new sown wheat, in my father’s castle field, no less

than eighty pheasants at one time. Fifty years later, on my last visit to the

old castle, I saw rise out of the same field fifty beautiful pheasant cock,

when they soon buried themselves in the vast forest around the old castle. It

was here Redman, the poacher’s gun burst and blew out

his eye. It was also here Frank, the keeper, shot a large eagle near the old

castle, which is now preserved.

Kilton Hall in about 1890

Kilton Hall in 2016

1.3 Stank House Farm

A considerable amount of ridge and

furrow evidence in the vicinity of the present Stank House Farm and the

earthworks suggest a medieval farmstead in two fields to the east of the

present farm. The name of the farm suggests a fish pond

and was probably derived from the fish pond at the Castle, which is close to

the site.

Two farms are shown on the 1767 map, one

on the site of the medieval earthworks and the other to the west. In 1767 the

farmhouse stood at the head of a long close, just to the west of a post

medieval track. It had no outbuildings. The building was much the same in 1845,

but by 1856 it had gained a courtyard arrangement of outbuildings.

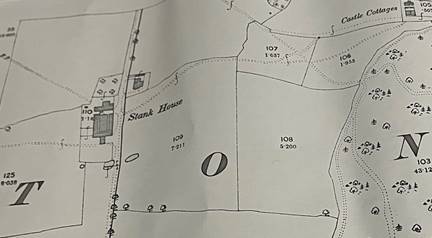

Stank House, 1853

Stank House 1856

Stank House in 1893

In 1882 a fine brick farmhouse, more

redolent of railway than rural architecture, was constructed to the east of the

eighteenth-century farmhouse and probably contemporary with this an extra block

of buildings was inserted into the courtyard arrangement. The farm stands like

this today with no trace of the 18th century farmhouse.

Stank House Farm in about 2016

1.4 Buck Rush

There are no medieval earthworks at the

present site of Buck Rush Farm, but there are some to the east. There are also

the remains of a possible house platform.

The estate map of 1767 provides shows

the site occupied by the lodge, a complex of three buildings with an enclosure,

the boundary of which crosses ridge and furrow excavations. There is a

rectangular enclosure containing a plantation to the north of the buildings.

This is probably a post medieval hunting lodge with direct access to the woods.

The 1856 Ordnance Survey map describes the woods as Lodge Woods. The 1767 map

also had also shown a farmstead at Buck Rush, to the west of the lodge. In 1767

this comprised two buildings, and a kiln field to the southeast may suggest

that their construction provided lime for mortar as well as for the fields.

Between 1845 and 1857 Buck Rush developed into a courtyard farm and the

buildings from the mid eighteenth century disappeared.

Buck Rush 1853

The present farmstead at buck rush

comprises a late 19th century stone farmhouse with a courtyard arrangement

dated from the mid nineteenth century.

Buck Rush Farm about 1912,

part of Kilton Lodge Farm under Charles Farndale.

1.5 Greenhills

The name Greenhills is applied to the

western arm of Kilton and may be derived from grundales,

meaning green strips, suggesting strips not always under plough. There are

extensive ridge and furrow excavations but no medieval

earthworks have been found. There must have been at least one farmstead in this

area in medieval times.

The 1767 map records three farmsteads in

this part of Kilton, one adjacent to Rough Close with a farm building and

enclosure; a second adjacent to Well Close and comprising four buildings within

an enclosure; and the third being a group of three building situated at

Greenhills on the west part of Kilton. The complex of buildings at Greenhills

developed between 1845 and 1856, but did not

constitute a courtyard farm.

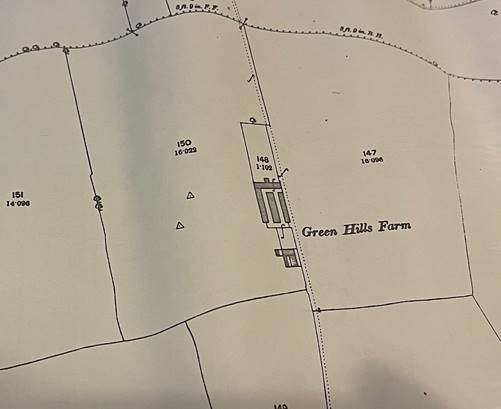

Green Hills Farm, 1893

In the late nineteenth century

Greenhills farm moved and it may occupy much the same position as the eighteenth century farm at Rough Close. The farm survives

today.

1.6 Lumpsey

There is extensive ridge and furrow work

in the area of Lumpsey,

which suggests medieval agriculture.

The estate plan of 1767 shows a

farmhouse and a range of buildings at Lumpsey, as

does the tithe map.

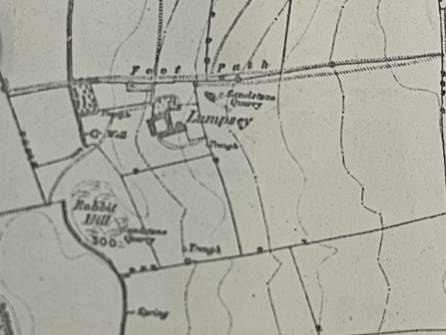

Lumpsey, 1853

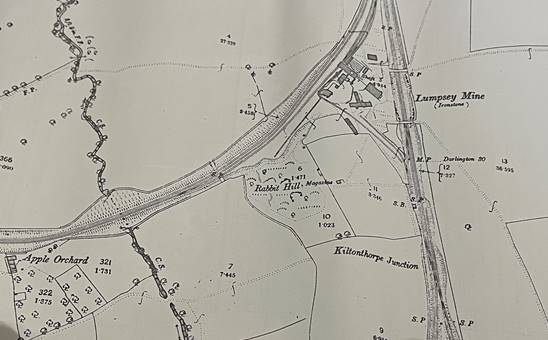

Lumpsey Mines by 1893

Lumpsey Mines in 1913

By 1856 this had developed into a

courtyard farm.

The establishment of an ironstone mine in this area in the

late nineteenth century led to the destruction of the farm and no buildings

survive. The Lumpsey mine was opened in 1881 as the

ironstone companies followed the veins south and east from the Eston hills. The

mine occupied the former site of Lumpsey farm and

consequently no traces were left of the farm. The mine closed in 1954 but a number of the mine buildings still survive.

1.7 Kilton Castle

Kilton Castle occupies a promontory of

land over the precipitous valley of Kilton Beck. The promontory is long and

narrow and therefore dictated the shape of the castle. There is a steep drop to

the south and consequently this area was never defended by anything other than

a wall. Access to the castle was via a narrow neck of land to the West. The

first documentary reference to the castle was in 1265, when a chantry was

granted to the Chapel there. Buildings must have been must have therefore

existed before that time. An Inquisition Post Mortem of 1355 recorded: “… at Kilton a

certain little castle and nothing of value with the walls and ditches that is

able to be repaired for less than 41s per annum…” The castle was probably

ruined by this time.

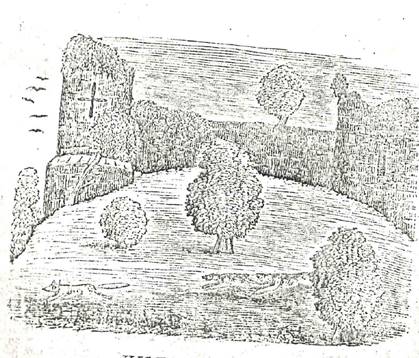

In The

History of Kilton, With a Sketch of the Neighbouring Villages, By the Returned

Emigrant, Dedicated to the Rev William Jolley, Toronto, Canada, America,

Middlesbrough, Burnett & Hood, “Exchange” Printing Offices, 1870, Redcar

Cleveland Library Book No: R000040114 Classification: 942.854, Book No:

R000040114, John Farndale

reproduced this drawing:

Kilton Castle. In this figure is represented Old Reynard

and the two dogs that took him as he leaped from the Watch Tower in the

presence of the Author, and Consitt Dryden Esq., sixty years ago

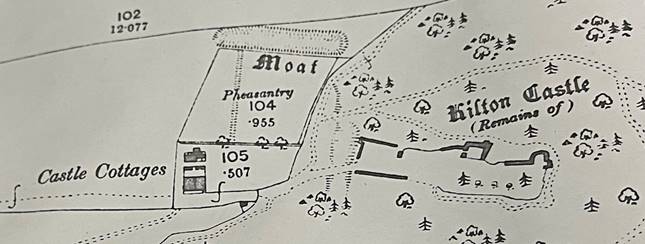

The 1767 map shows a close in front of

the castle, while the tithe map shows no detail for this area. The 1856 map

depicts two features which were described as moats, but which are more likely

to be the fish ponds. Two buildings joined this and

were probably the forerunners of the estate cottages which were built here in

the late nineteenth century. Of the castle, the Reverend John Graves wrote at

the beginning of the nineteenth century “… the edifice is now in so ruinous

a state, as to render it impossible to form any idea of its former strength and

magnificence... the ruins... are seen on the point of a rugged steep, washed by

a mountain stream, brawling among fragments of rock, at a great depth beneath.

The banks of the river rise swiftly, and being wooded on either hand, encompass

the point on which the castle stands, and forms a picturesque foreground....”

The castle remains a picturesque ruin,

but a row of a state cottages in the same style as those at Kilton were built

in the late 19th century. The northern arm of the fish pond

is still visible as a depression within a field, but the southern arm has

disappeared altogether.

The remains of Kilton Castle, 1893

The remains of

Kilton Castle in 1913

1.8 Kilton Woods and Kilton Beck

In A Guide

to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding District, With remarks on its

picturesque scenery, Fifth Edition, Dedicated to John Thomas Wharton Esq of

Skelton, By John

Farndale. Late of Skelton Castle Farm, Darlington, Printed by Charles W

Hird, 1864, John

Farndale wrote:

Kilton is a small village, but the vale

in which it stands abounds with woodland scenery. At a short distance

stands the remains of the old castle of Kilton, which once belonged to the Thwings, where centuries ago there were no doubt great

doings; but time here has wrought vast changes, and the history of this once

important stronghold is now nearly buried in oblivion.

From the ruins of the castle there is a

fine view of the vast forest in which it stands, with the river crawling

through blocks of huge stones till it reaches the sea at Skinningrove. Here

I remember planting, fifty years ago, the first trees near the old castle

walls, and they are now as lofty as their sires two hundred years old.

Here as I stand how reflection crowds my mind. There is no corner of this wood

unknown to me. I have traversed it a thousand times when a boy. I have captured

in it the owl, the crow, the cushat, the hawk, the cuckoo, and every other

forest bird, and also the squirrel, the weasel, the

foumart, the badger, the snake and the fox. How often I have heard the

retreat of the huntsman’s horn, like Joab at the death of Absolom, and how

exulted when three cheers proclaimed the death of poor Reynard. I remember once

the fox hard run by the Cleveland and Roxby hounds, and he took refuge between

the old castle walls and the ivy creeping between. Here he kept safe till the

hounds came up, when he boldly bounced in the very face of his enemies, and was soon overcome. Mr J Codling, of Roxby,

caught him yet alive, and brushed him in the presence of Consett Dryden Esq., myself and a few others, and

we made the wood resound with three cheers.

Here in the spring

time when Nature is bursting into new life and beauty, and every hill is

carpeted with wild flowers, when the feathered choir sing in joyful and

delightful concert, and the busy bee with its drony

tone passes and repasses, how sweety it is to stand and admire the skill and

muse the praise of Him who brought them into being.

Kilton Woods

Here blooming flowers, with fragrant

lips,

Sweet pleasure gives to me,

While happy birds with gladsome voice

Now flirt from tree to tree.

The river as it onward flows

Its pleasant winding way,

Sings with smiles of calm content

Its message day by day.

On mountain high and valley low

The voice of God I hear,

And by the sea, the rippling sea,

I ever feel him near.

I gaze upon the silent night

And in the heavens above,

And in golden letters, clear and bright,

The stars sing

God is love.

The cuckoo with her well known voice,

Sings ever as she flies,

And joyful tidings brings

to all,

She never tells us lies.

She sucks the eggs of other birds,

Which makes her voice more clear;

And when she sings, gay spring is come

And summer’s drawing near.

Petrifying springs, depositing carbonate

of lime, abound in this locality. Amongst the most remarkable may be noticed a spring in

Kilton Wood, a little to the south of the castle, and a remarkable sulphurous

spring, which issues from the aluminous schistus on

the banks of the beck near Kilton Mill. One gallon of water of this spring was

found to be seventy two garins

heavier than a gallon of distilled water. In the immediate vicinity of Kilton

Castle there is also another petrifying spring, depositing carbonate of lime.

1.9 Kilton Mill

A mill is noted at Kilton in 1323 and

1344 when it was worth 30s per annum. The 1767 map shows a mill perhaps in the

approximate location of the medieval mill.

The 1767 map shows a complex of at least

three buildings, wrongly labelled as Wilton Mill. The mill building is shown

extending over the stream and the wheel may have been contained within a

housing. The complex changed little by 1845, but by 1856 it had grown with the

addition of a courtyard farm.

A large nineteenth century mill with its

outbuilding still stands on Kilton beck and may occupy much the same location

as its medieval predecessor. It is no longer used for milling purposes.

1.10 Chapel Fields

These three fields lie on a medieval

trackway from Kilton and were given the name Chapel Fields on the 1767 map and

the 1845 tithe map. The significance of the name is not obvious. Perhaps a

chapel once stood in these fields or perhaps the rent from the fields were

provided for the upkeep of a chapel.

1.11 Kilton Thorpe

The form and extent of the medieval

settlement at Kilton Thorpe is difficult to determine. An area of worth

earthworks survives at the northwest corner of the present village.

Three buildings were shown on the 1767

map and by 1845 these had shrunk to two. In 1857 those buildings to the south

of the road had disappeared altogether, to be replaced by a single building set

back from the road and at right angles to it. The buildings to the north of the

road had been extended possibly with the construction of a state cottages and

another farmstead.

Kilton Thorpe and Kilton Mines, 1893

1.12 Kilton Mines

The Kilton mines were sited to the south of Kilton

Thorpe and were opened in 1871. Their main impact on Kilton had been the

creation of a large spoil tip which continues to dominate the skyline. Both

Kilton and Lumpsey mines were served by railways and

the abandoned embankments and cuttings of the railways are still visible.

The remains of the mine works at Kilton

in 2016:

Chapter 2 - The History of

Kilton

There is evidence of an initial pattern

of dispersed settlement of individual farmsteads in prehistoric times.

2.1 Medieval Kilton

Kilton lies to the north

east of the North York Moors within the parish of Skelton. The name

Kilton may be derived from the Scandinavian language, and

may refer to a farm settlement in a narrow valley.

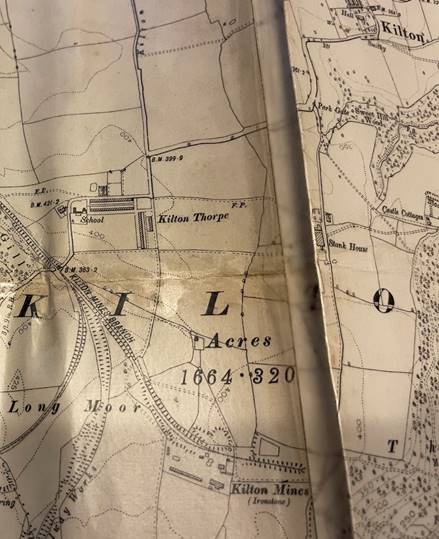

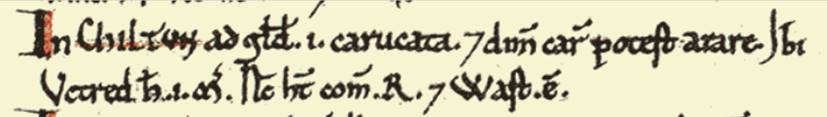

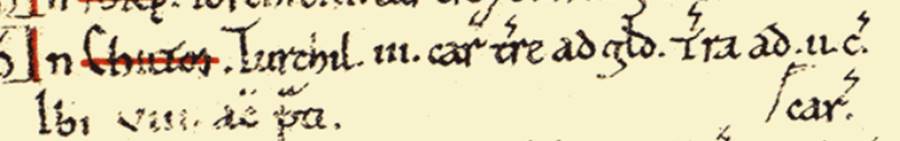

1086

The village is record in the Domesday Book, 1086 when it was called Chitune. Before the Norman Conquest, it was the land

of Uhtred.

Kilton Thorpe was also mentioned in the

Domesday Book as Thorpe, a Scandinavian word for a small settlement.

Doomsday Book states that the King held land at both Kilton (“Chitune”) and Kilton Thorpe (“Thorpe”). Since

there were many Thorpes in northern England, the settlement became known as

Kilton Thorpe. At Kilton Thorpe there was a manor and one and a half caracutes of land and at Kilton, one caracute.

The land around Kilton and Skinningrove

was given to the de Brus family at the time of the Norman Conquest. Both

Kilton and Kilton Thorpe were held for the King by the Count of Mortain. However he was banished

for conspiracy in 1088 and both villages, the two and a half caracutes, another five and a half caracutes

and eight acres of meadow passed to Robert de Brus. At this time the

manor of Little Moorsholm also formed part of the

Kilton Fee. That of Great Moorsholm did not join the Kilton Fee until 1272. It

seems too that the Soke of South Loftus, six caracutes of land, joined the Kilton Fee soon after the

Doomsday survey. North Loftus was much bigger and was part of the Chester Fee.

1106

Alan de Percy founded the Fief of Kilton in the

Barony of Percy in 1106. His tenant was Walter who subdivided the fiefdom into

(1) the Fief of Kilton proper; (2) the Lordship of Hinderwell; and (3) the

Lordship of Kirkleatham. In the Fief of Kilton there were the manors of Kilton

Thorpe and Little Moorsholm the Soke of South Loftus.

1135

Kilton Castle was probably founded by Pagan

Fitzwalter de Thweng (b 1080) and built in about 1135

to 1140, initially in timber.

1140

By 1140 his son Osbert began the stone

construction (the local orange-brown sandstone).

1166

In 1166 the subtenant of Kilton was

"Ilger de Kilton" and remained so until

1190.

1190

The castle was probably finished by

William de Kylton between 1190 and 1200. Ord in the History of

Cleveland wrote: "As

a fortress, it must have proved impregnable previous to the introduction of

artillery; being placed on a high jutting eminence, surrounded by steep

precipices, except to the west, where the ditches, foss,

inner vallum, and traces of the barbican gate are distinctly observable."

The castle was built on a promontory of rock above Kilton Beck with steep

valley walls plunging about 90 metres down to the Beck. The ground on the far

side of the Beck rose to a similar height, but sufficiently distant from the

castle to be a threat. To the west was a narrow strip of land protected by a

deep ditch on either side. Ord in the History of

Cleveland considered the castle

to be the “"most powerful baronial fortress in Cleveland.” Within

the inner ward the Castle had a Great Hall, kitchens, a private chapel and the apartments of the Lord of the Manor. In time,

the Castle had gardens, and a fishpond. However the

Castle was unusual by not having a Keep, which may have caused it to be

obsolete by the fourteenth century.

Kilton Castle, in the collection at

Kirkleatham Museum

Kilton Castle in 2016

(it takes a bit of finding!)

1215

Peter de Mauley tried to besiege the

castle between 1215 and 1216 when Sir Richard de Autrey occupied the castle.

After King John’s death in 1216, a settlement was agreed between de Mauley and

de Autrey.

1222

In 1222 de Autrey died and his widow,

still aged only 22, was given by the owner of Kilton Castle, Sir William de Kylton, to Sir Robert de Thweng

(1205 to 1268) through marriage to Matilda de Kylton,

niece of Sir William de Kylton and widow of Richard

de Autrey. This coincided with a dispute with the prior of Guisborough about

the ownership.

1232

After an attempted appeal to Rome, the

frustrated Sir Robert rebelled and raided church property in about 1232, using the

nickname Will Wither, or William the Angry. It is said that he then

distributed the spoils, Robin Hood like, to

the poor. He was excommunicated in consequence, but was

supported by other local noble families including the Houses of de Brus, Percy

and Neville. Another appeal to Henry III met with royal support and Pope

Gregory IX was persuaded to rule in his favour. The rebellion came to an end.

1257

When Sir Robert died in about 1257,

the castle passed to his son, Marmaduke de Thweng,

who had married Lucia de Brus in about 1247 and had been born and baptised

at Kilton Castle in 1225. His eldest son Robert was born at Kilton

Castle in 1255, then came seven more sons and five daughters, the last

born in 1276. The second son Marmaduke born in Kilton Castle in 1256

moved to Danby and Kilton went to his eldest son Robert who died in 1279

leaving only a daughter Lucia.

1285

In 1285, after Marmaduke’s death,

Lucia de Thweng (born in Kilton castle in 1279

and baptised in the castle chapel) inherited her father’s lands, initially

through the custody of the King, until she came of age.

1305

Lucia was married, against her will, to

William de Latimer, but they were divorced in 1305 after Lucia famously

eloped with a Knight. Lucia returned to Kilton Castle, though it is possible

that even by this date, the castle was falling into ruin. Lucia (who died in January

1347) by design avoided the de Thweng estates

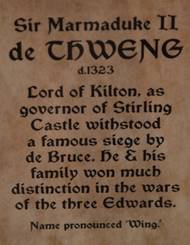

falling to her own sons, and ownership of Kilton passed to Lucia’s Uncle, Marmarduke Thweng, the

First Baron Thweng.

1341

The First Baron’s son died without heir,

and his grandson was killed at the Battle of Stirling Bridge, and so, in 1341,

the castle passed to his eldest daughter, Lucia de Lumley.

From the collection at

Kirleatham Museum.

Marmaduke II de Thweng played a prominent part in the

Scottish wars and a major part in the Battle of Stirling on 11 September

1297 where his eldest son Marmaduke was killed.

1537

The castle stayed in the hands of the

Lumley family until 1537 when George Lumley was executed for his

participation in the Pilgrimage of Grace (the Yorkshire based uprising of 1536

protesting against Henry VIII’s break with the

Catholic Church). The Crown then took possession of the castle and certainly by

the end of the sixteenth century, the castle was in total ruin.

The already ruined castle may also have

taken another hammering during the Civil War since in

A Guide to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding District, With remarks on

its picturesque scenery, Fifth Edition, Dedicated to John Thomas Wharton Esq of

Skelton, By John

Farndale. Late of Skelton Castle Farm, Darlington, Printed by Charles W

Hird, 1864, John

Farndale wrote “When Cromwell came that way, He heard the bell

at noon; Fixed his cannon as they say, And brought the castle down.” Yet,

not all – as some still remains, cemented together

like iron bound with ivy, for ages to come:

“All ruins

are lovely when o’er them is cast

The green

veil of ivy to shadow the past;

When the

rent and the chasm fearfully yawned,

By the moss

of the lichen are sweetly adorned.

When the

long grass doth carpet the desolate halls.

And tress

have sprung up in the old withered walls,

And woven a

curtain of loveliest green,

Where once

the rich folds of the damask were seen.

But such

thoughts are unheeded while idly we gaze,

On the

desolate grandeur of earlier days;

‘Tis the

wreck that is lovely, the wider the rent

The fuller

the view of the landscape is lent.

The wind

that now sighs through the tenantless hall

No thoughts

of loved voices to memory call;

All ruins

are lovely when o’er them is cast

The green

veil of ivy to shadow the past.”

In The

History of Kilton, With a Sketch of the Neighbouring Villages, By the Returned

Emigrant, Dedicated to the Rev William Jolley, Toronto, Canada, America,

Middlesbrough, Burnett & Hood, “Exchange” Printing Offices, 1870, Redcar

Cleveland Library Book No: R000040114 Classification: 942.854, Book No:

R000040114, John Farndale wrote: Camden, in speaking of Kilton and Kilton Old Castle, as

Farndale has it in his Guide to Saltburn by the Sea, says “It is situated in a

park belonging to the ancient families of Thweng

and Lumley’s. Baron Lumley, of Kilton Castle, died in battle, having joined

the Earl of Kent and others to restore King Richard, then deposed. Kilton

Manors, for there were two, became forfeited to the crown, but restored to

the Thwing’s and Lumbley’s, by Henry IV, and by marriage to Wm Tulley Esq., who died at Kilton Hall, and was interred in Brotton

Church 1741, aged 72 years. Then to Dr Waugh, of Carlisle, and next in kin to

the Misses Waugh, who sold the estate to Miss Wharton, of Thirsk Hall, a rich

old lady, and this lady presented it as a gift to her nephew, J Hall Wharton Esq., MP, and now it is the property of JT Wharton Esq., of Skelton Castle. At the above date Kilton Hall was

then a beautiful building, much admired. Mr Ord, in giving a description of

Kilton Castle, says “Few ruins in England can equal this venerable relic of

antiquity – as a fortress it must have proved impregnable previous

to the introduction of artillery. Standing on a high triangular

precipice unapproachable except on the west, and here it was defended by

a moat and draw bridge, and large massive gate way

doors”

The castle would have provided economic

opportunities for the surrounding countryside. When the Castle was inhabited,

there was a village of some size occupying the site of the modern farmstead of

Kilton Hall, some 600 metres north west of the Castle.

There was a park attached the castle which was described in 1323 as “… a

certain park without beasts of the chase in which there was no profit apart

from herbage thereof …”

Adjacent to the Castle, medieval Kilton

comprised both Kilton and Kilton Thorpe and there were farmsteads at Stank

House, Buck Rush and Greenhills. The farming was

probably of a mixed nature, growing cereals and rearing sheep and cattle. Teams

of oxen ploughed up one side of each strip and turned the soil towards the

centre creating the ‘ridge and farrow’ corrugations which are still visible

today. Blocks of ridge and farrow were called furlongs and at the end of each

strip was a headland, where the ploughs were lifted from the soil and turned

around.

Ridge and farrow corrugation at Kilton,

taken in 2016

There was milling at Kilton Mill. The road

from Brotton to Kilton probably dates to the medieval period as the ridge and

furrow archaeology is consistent with this. The road from Kilton to Kilton

Thorpe is also medieval. The amount of ridge and farrow in

the area of Kilton suggests that almost all the land was cultivated.

2.2 Sixteenth Century

1537

By 1537 when the Crown took possession of Kilton Castle it was a gaunt, grim, ivy clad ruin. Thereafter it was used as a local source of building material. There is a story that Kilton was besieged and destroyed by Cromwell (see John Farndale’s narration above) but this is most unlikely as by that time it had been uninhabited for 240 years.

2.3 Seventeenth Century

1680

About 1680 a Mr Thomas Thweng purchased the Castle from the Crown, probably a descendant of a junior branch of the family. He certainly did not live there and it was probably he who built the original Kilton Hall some one mile away from its stone. His only daughter Ann married Mr William Tully and at the east end of the chancel of old Brotton church (now no more) was a large memorial which said "Sacred memory of William Tully of Kilton in this county, Esq, who departed this life 27 May 1741 aged 72 and is interned underneath this monument. He married Ann sole daughter and heiress of Thomas Thweng of Kilton Castle in this county, Esq, by whom he left no issue."

2.4 Eighteenth Century

In the eighteenth century, the medieval fields

were enclosed, and the farmsteads had moved to their present locations.

1754

The Newcastle

Courant, 30 March 1754: To be Sold. Now Growing at Kilton, within

two miles of the Sra, near Guisborough, in Cleveland, Yorkshire. A Large

Quantity of full groan OAK, ASH and ELM &c For

further particulars, inquire of William Jackson of Guisborough, who will fell

said trees.

1770

Adam's Weekly Courant, 11

December 1770 reported on

Mr Turner’s Hounds (the hunt founded by the smuggler, Andrew Turner, later the

Roxby and Cleveland Foxhounds) which passed through Kilton.

1771

Perhaps the start of a constant

battle between landowners and tenants and poachers, could have started with

a report by the Newcastle Chronicle, or, General

Weekly Advertiser, 24 August 1771: Whereas the Game and Fish within

the Lordship or Manor of Kilton, in the North Riding of the County of York, have,

of late years, been greatly destroyed in the night and at other times, by

poachers and other persons, without the leave of Joseph Tullie Esquire, Lord of

the said Manor; Notice is hereby given, that all unqualified persons killing

game or fish within the said Lordship, will be prosecuted with the utmost

rigour: and it is particularly requested that no gentleman will hunt, shoot, or

fish within the said Lordship, without Leave in Writing of the said Mr Tullie.

1778

The Newcastle

Chronicle, 18 July 1778: LOFTHOUSE BRIDGE. Any person willing to

contract for the building of a Carriage Bridge over the brook dividing the

townships of Lofthouse and Kilton, near to the highway leading from Kilton to

Lofthouse aforesaid, may deliver in a plan and proposals as soon as possible,

to Mr Lawson of Stokesley. Mr Farquharson of Lofthouse will show the place

where the intended bridge is to be erected.

1786

John Wharton (21 June 1765 – 29 May

1843) was a British landowner and member of Parliament. He was the eldest son

of Joseph William Hall-Stevenson of Skelton, John Wharton succeeded his father

in 1786, inheriting the ruinous Skelton Castle. He demolished the old Skelton

Castle and between 1788 and 1817 built a similarly named Gothic country house

in its place. By 1829 he was in debt and spent the next 14 years in the Fleet

Debtors Prison, where he died childless in 1843. He had married Susan Mary

Anne, the daughter of General John Lambton of Lambton, County Durham. He had

two daughters who both predeceased him and was succeeded by his nephew, John

Thomas Wharton.

John Thomas Wharton, to whom John

Farndale’s book is dedicated, was born in York on 9 March 1795 and died at

Tadcaster on 25 September 1871, aged 76. His uncle, John Wharton died childless

and in poverty in 1843 and Skelton devolved to John Thomas Wharton of Gilling.

John Wharton of Skelton Castle was the

Squire of Kilton.

In The History of Kilton, With a Sketch of the Neighbouring Villages, By the Returned

Emigrant, Dedicated to the Rev William Jolley, Toronto, Canada, America,

Middlesbrough, Burnett & Hood, “Exchange” Printing Offices, 1870, Redcar

Cleveland Library Book No: R000040114 Classification: 942.854, Book No:

R000040114, John Farndale imagined his return to

Kilton after years of absence when he recalled:

…

some one hundred and twenty parents and children, besides men-servants

and women-servants; I remember ten farmers occupant of some seven

hundred acres of land, and now it’s absorbed into one large farm, by laying

field to field, and adding farm to farm. Surely this gentleman must be Lord of

Kilton Manors, for formerly it comprised two Manors. Then he asked, where are

all those respected farmers? Had they and their sons to find a home in some

far-away land, and to perish out of sight? I see in the book recorded and registered

in olden time, the names of farmers who once occupied this great farm – R

and W Jolly, M Young, R Mitchell; W Wood, J Harland, T Toas, J Readman, J

Farndale, S Farndale, J and W Farndale, all these tenants once occupied this

great farm; now blended into one.

I

remember what a muster at the Kilton rent days, twice a year, when dinner

was provided for a quarter of a hundred tenants, Brotton, Moorsholm, Stanghoe, those paid their rents at Kilton; and were indeed

belonging to the Kilton Court, kept here also, and the old matron proudly

provided a rich plum pudding and roast beef; and the steward also a jolly

punch bowl, for it was a pleasure to him to take the rents at Kilton, the day

before Skelton rent day. The steward always called old J Farndale to the

vice-chair, he being old, and the oldest tenant. Farndale’s

was the most numerous family, and had lived on the

estate for many ages. Kilton had many mechanics, and here we had a

public house, a meeting house, two lodging houses, and a school

house, to learn our ABCs, from which sprang two eminent school masters, who

became extremely popular; we had a butcher’s shop, we had a London

tailor and is apprentice, and eight other apprentices more; we had a rag

merchant and a shop which sold song books, pins, needles, tape and thread;

we had five sailors, two soldiers, two missionaries, besides a number of

old people, aged 80, 90 and 100 years. But last, not least, Wm Tulley Esq., who took so much interest in the old castle – planted

its orchard, bowling green, and made fish ponds, which

were fed by a reservoir near the Park House, Kiltonthorpe,

Kilton Lodge, together with all these improvements around the castle, which are

now no more.

In A Guide to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding

District, With remarks on its picturesque scenery, Fifth Edition, Dedicated to

John Thomas Wharton Esq of Skelton, By John

Farndale. Late of Skelton Castle Farm, Darlington, Printed by Charles W

Hird, 1864, John Farndale wrote of the late eighteenth century:

Kilton formerly contained a few tradesmen

– namely two joiners, two coopers, two weavers, one butcher, a publican, a

water miller, a rag merchant, an old man with nine children, two sailors, and a

banker’s cashier. At one time it had four sailors – one was taken

prisoner in the French War, an old man, aged 87, and yet living – another,

a missionary to the French prisoners, died in France, aged 87, a noble fellow,

was formerly in the Life Guards. Seventy years ago Kilton had eight farmers; it now has only one. It

had then fifty four children, now only seven – then

twenty four parents, now only five – and then nine old men and women rom eighty to one hundred and five years of age. The

inhabitants of this village, as may be expected, were long lived; most of the

old men were of the giant tribe, their ages averaging at death eighty seven years. My children’s children comprise the

sixth generation of our family that has lived at Kilton estate upwards of two

hundred years.

In former days the inhabitants of this

district were Jacks, and Toms, and Mats; now they are either Misters or

Esquires, and thick as mushrooms around us. In those days there were no

Mistresses or Ladies among them, they were all Dames – there wore no silk gowns, no veils, no crinolines, no bustles;

but home spun garments, giving employment to the inhabitants, warmth and comfort to the wearers, and lasting for fifty

years. Specimens at home.

John Farndale

recalled one family named Swales noted for oddness and

singularity of manners. When they dined together they

all dipped into one dish. The parent once called out for bread, exclaiming “I

eat bread to every thing.” A

little urchin answered “Now, Fadder, thou lies, thou doesn’t eat bread to cake!” When the old man

died, a large multitude gathered at his funeral. He was brought through Kilton

to Brotton to be buried, and this youth was noticed last at the grave side, and

looking into the grace he at length broke the silence and said “Farewll, fadder!” and a second

time he said, “Farewell, fadder!” and a third time,

with all his might, making the welkin ring, he exclaimed, “Farewell, fadder!” and then left the graveside with a sad heart and a

sorrowful countenance. The end of this rough, untutored fellow was untimely. In

an evil hour his cart overturned over him, and two nights and a day he lay

dying. The following lines he intended for his tombstone:-

“Whea lies here? Whea dye think?

Poor Willy

Swales, he loved a drop o’ drink.

Drink to him

as you pass by,

For poor

Willy Swales was always dry.”

There was another servant of my

father’s, named Ralph Page, equally as singular as Willy Swales. As Ralph

was once busily ploughing, a French Privateer, threatening land at

Skinningrove, fired into the town. Those in the district who had guns

assembled on the cliffs and fired a volley in return. To intimidate the

enemy the women mustered strong and attired in red cloaks and shouldering

sticks, to represent a body of soldiers, they stood far away in the

distance. Ralph took little notice of the privateer, not bothering his head

either with the French or the English, only they let him be, when a young woman

passing in haste, cried out “Ralph, French is landing.”. Ralph, turning round,

with the greatest coolness replied, “Then run yam, and sup all’t

cream,” and unconcerned he ploughed away as though nothing was the matter.

The next day the king’s cutter arrived,

and the privateer and her had an engagement, when the Frenchmen were beaten and

the vessel taken, to the great joy of the inhabitants of the surrounding

district.

Here let me narrate one anecdote more or

a man whom I well knew, and who lived and died at Moorsholm.

There was an assize trial at York, about a water course

running under ground, and Paul, for that was the man’s name, who was a fine

upright fellow, with a high brow and a bluff face, had to appear as a witness

on the occasion. When Paul went into the witness box, the counsellor on

the opposite side having silenced a man of letters, very promptly said to Paul,

as he stared at him, “Well Mr Baconface, and what

have you to say on the subject?” “Whya.” Replied

Paul, with a significant grin, “If my bacon face and thy calf face were boiled together they wad mak good broth!”

The councillor looked abashed, and the whole court roared with laughter. The

counsellor recvering his self

possession, then tried to put Paul into a fix about the watercourse

by inquiring what he knew about it, and in a triumphant tone of voice he said,

“And how, my man, do you know that the same water ran out of the course that

ran into it?” “How did I know that?” reiterated Paul, “Whya,

I tuek care thou sees t’ muddy watter

before it went in, and it cam

out muddy.” The court enjoyed a hearty laugh, and the result was, the

learned councillor lost his cause.

1795

Kilton Hall 1795 sketched by John

Farndale

1799

The Hull

Advertiser, 19 January 1799: Education. Miss Greens’ respectfully

acquaint their friends and the public that their school opens again on

Monday 21, at Kilton Lodge, near Guisborough, where YOUNG LADSIES are

taught every branch of useful and ornamental education on the following terms:

Entrance £1 1 0. Board, English grammar, and every kind of needle work £16 16

0. Writing and arithmetic £1 1 0. Geography £1 1 0. Use of piana

forte £1 4 0. Use of drawers £0 5 0. Each Young Lady to bring a pair

of sheets, two towels, spoon, knife and fork, or pay

one Guinea for the use of them.

The

Impact of Agricultural Change on the Rural

Community - a case study of Kilton circa 1770-1870, Janet Dowey: The

most predominant family at Kilton was the Farndales, their ancestry ages old.

Its most distinguished member John Farndale wrote numerous books on the area.

Kilton, the village itself had been a thriving community consisting of a

public house, a meeting house, two lodging houses and a schoolhouse, from which

sprang two eminent schoolmasters. A butcher's shop, a London tailor and his apprentice and eight others, a rag merchant,

a shop which sold some books, pens, needles, tape and thread. Five sailors, two

soldiers, two missionaries plus a number of very old

people.

The picture John Farndale paints is of a peaceful rural community who

boasted of no poachers, no cockfighters, no drunkards or swearers. A church

going people who met together on a Sunday afternoon. Kilton at that time had

nearly 20 houses and a population of 140 men, women and children, a Hall,

stables, plantation and the old Castle plus 12 small

farms. When John wrote these books he was speaking

of a time long since gone (the early nineteenth century), he listed each family

that lives lived within the village.

Robert Jolly was a farmer and a staunch Wesleyan. After his death his farm was

carried on awhile by his sons. This being the time of Nelson's death (1805),

John goes on to say that there was great reformation in Kilton estate,

"the little farms were joined together, about 150 acres each. Every farmer

had to move to a new farm. The sons of Robert Jolly each moved away at this

time, one became a lifeguard to George III and the other eventually became a

minister. William Bulmer was another native of Kilton and married with nine

children, he made his living buying and selling, but all his children moved

away into 'respectable' situations."

Many of the farmers were weavers too, one in particular,

George Bennison, had two looms plus his land and also prepared a colt

for Northallerton fair once a year stop. The children of these farmers

continually moved away from the district and agriculture. John Farndale says "and now they disappear, but where are they gone,

I know not". John Tuke says "it is observable, but in those families

which have succeeded from generation to generation to the same farm, the

strongest attachment to old customs prevails. For conduct and character, the

farmer under survey must deservedly rank high among their fellows in any part

of England, they are generally sober, industrious and

orderly; most of the younger part of them have enjoyed a proper education, and

give a suitable one to their children, who, of both sexes, are brought up in

habits of industry and economy. Such conduct rarely fails meeting its reward;

they who merit, and seek it, obtain independence, and every generation, or part

of every generation, may be seen stepping forward to a scale in society

somewhat beyond the last."

However Thomas Hardy in his book "Tess of the D'Urbervilles", states

"all mutations so increasingly discernible in village life did not

originate entirely in the agricultural unrest. A depopulation was going

on." The village life which Hardy talks about had previously

"contained" side by side with agricultural labourers an

"interesting and better informed class".

These included a carpenter, a Smith, shoemaker, huckster "together with

nondescript workers" in addition to the farm labourers. A group of people

who "owed a certain stability of aim and conduct to the fact of their

being life-holders or copyholders or occasionally small freeholders." When

the long holdings fell in they were rarely again let

to identical tenants, and they were usually pulled down, if they were not

needed by the farmer or his workers. "Cottagers who were not directly

employed on the land were looked upon with disfavour, and the banishment of some

starved the trade of others, who were thus obliged to follow." Families

such as these had formed the backbone of the village life in the past who were

the depositories of the village traditions, had to seek refuge in the large

centres; the process, designated by statisticians as the tendency of the rural

population towards the large towns being really the tendency of water to flow

uphill when forced by machinery.

1806

The

Yorkshire Herald and the York Herald, 21 Jun 1806,

Sat ·Page 3 reported the death of George Thompson of Kilton on 29 May

1806 who had been master of a ship, the Glory, of 98 guns, who had been

involved in more than 25 engagements across the world during his life.

1809

The Skelton and Kilton

Terrier in 1809 provided a detailed record of the tenanted farmland in

1809. A ‘terrier’ is a record of field names, with

reference number, land use, acreage, value per acre and rent.

The Kelton land included records of the landholdings of

William Bennison, George Bennison, William Farndale (FAR00183),

Robert Solley, Robert Barker, Ralph Newbiggin, William Stephenson, Ralph

Mitchell, John Farndale (FAR00167), and

William Wood.

1817

The Yorkshire

Herald and the York Herald, 22 Nov 1817, Sat ·Page 3 reported that the

Roxby and Cleveland Foxhounds were to meet at Kilton Mill Monday 24 November

1817. There were many similar notices over the following years. The Roxby and

Cleveland Hounds were formed by the notorious smuggler, John Andrew of the

White House at Saltburn.

1822

The Topographical Dictionary of Yorkshire by Thomas Langdale of

1822 described Kilton, in the parish of Skelton, east

division of the wapentake and liberty of Langbaraugh, 7 miles from Guisbrough,

15 from Stokesley, 16 from Whitby, population 129. Kilton Thorpe was also

listed with the same description, but no population was given.

1823

The Yorkshire

Herald and the York Herald 22 Nov 1823, Sat ·Page 1 reported that man

traps and spring guns had been set in the woods, plantations

and pleasure grounds of John Wharton Esq at Skelton, Kilton, Brotton and Great

Moorsholm to stop trespassers.

1825

The Yorkshire

Herald and the York Herald 11 Jun 1825, Sat ·Page 3 gave notice of the

diversion of a part of the highway at Skinningrove and Kilton leading from the

market town of Guisborough to Lofthouse, of a length of 344 yards and 15feet in

breadth, and for making a new highway “more commodious to the Public” to

replace that section from a lane at Kilton and Lofthouse and extending south

east and north east through and over the lands of John Wharton Esq and John

Maynard.

1833

There were general elections in 1832 and

1835. The Yorkshire Herald and the York Herald 14

Sep 1833, Sat ·Page 1 gave notice that the three

gentleman appointed to revise the list of voters for the North Riding of

the County of York would come to Guisborough on 11 October 1833 in order to

revise the list of voters for a number of towns including Kilton and Brotton.

1835

The Yorkshire

Herald and the York Herald 5 Sep 1835, Sat ·Page 1 gave notice that a Commissioner had been appointed to execute “An Act of for

Inclosing Lands in the Manor of Skelton, in Cleveland, in the County of York”

and in doing so the Kilton Road was to be divided and inclosed.

The Act of 1813 was passed for the enclosing of the lands of the manor of

Skelton and the Commissioner was appointed to make inquiries and examine

witness living within the manor boundaries.

2.5 Victorian Kilton

In the nineteenth century, the opening

of the Kilton and Lumpsey ironstone mines, and the

arrival of the railway into the township, had a major impact on the landscape.

The

Impact of Agricultural Change on the Rural

Community - a case study of Kilton circa 1770-1870, Janet Dowey: … The

Kilton John Farndale knew and loved …had changed beyond belief.

Several of the very old and larger states were less crowded than they had been;

where a better cultivation had taken place, the small cottages had given way

gradually to shape a farm worthy of the person having such money to improve it.

A lot of the field structures and hedges were still in place, only some of the

hedges had been taken out to make bigger fields. The hedge structure at Kilton

was probably there 50 years before John Farndale was born. In one instance a

hedge appears to have been put in to divide a field.

Some of the reasons for the demise of

Kilton were the industrial revolution, which was the need to centralise craftsmen from the small

villages, a revolution in farming methods and farming machinery, a wholesale

destruction of the village for the town. The Napoleonic Wars had an influence

on the price of farm produce, the price of food was kept at a fairly high level during the war but after the war finished

the price of grain fell to one of its lowest levels along with falling meat

prices, and disastrous harvests. Farming methods were needed to get the harvest

in quicker. This finally led the landlord to enlarge the farms and bring in a

farmer with money to modernise the farm. The mechanisation of farming policies

on the one hand and the progressive quantity of urban factories on the other,

combined to drastically alter that rural life. Taking into consideration also

the turnpike roads, the invention of the railway and the canal networks it is

obvious that economic and technological forces were bringing far reaching

changes. During the period when enclosure was in progress, "the revolution

in agricultural methods", there was moderately steady process of new

village creation, a considerable upsurge within the 18th century. Enclosure or

amalgamation of the Kilton village farms, probably happened in the late 1860s,

thus was the complete destruction of the village.

Kilton became a victim not only of the

"Monstre farm" but also of the Industrial

Revolution.

"And now dear Farndale, the best of friends

must part,

I bid you and your little Kilton along and final

farewell.

Time was on to all our precious boon,

Time is passing away so soon,

Time know more about his vast eternity,

World without end oceans without sure."

John Farndale. 1870

"Now much has changed, we oft times have looked and looked

again, but no corner of this large farm has been neglected. Witness, this rich

stack yard of 100 acres of wheat, the staff of life, and 100 more, oats, beans,

peas, hay, clover, potatoes and turnips piled up against the winter storms. In

the fold are housed 100 head of sheep, a stable with 14 farming horses, besides

the young horses, pigs and geese in abundance, carts, wagons, ploughs and

harrows and all implements.”

1839

The Yorkshire

Gazette, 2 November 1839 reported that Hannah Mitchell of Kilton won a

sovereign for the best cheese made out of the district

at the Whitby Cheese Fair.

1872

In Kelly’s

Post Office Directory of 1872: Kilton is a township, 6 miles north east by eat of Guisborough, and one south from

Brotton. Here was formerly a castle of which but few traces remain. Here are

church schools, recently erected and supported by John Thomas Wharton esq who

is lord of the manor and landowner. The population in 1861 was 93; in 1871,

222; acreage 1,723; gross estimated rental £1,731; rateable value £1,593.

In The

History of Kilton, With a Sketch of the Neighbouring Villages, By the Returned

Emigrant, Dedicated to the Rev William Jolley, Toronto, Canada, America,

Middlesbrough, Burnett & Hood, “Exchange” Printing Offices, 1870, Redcar

Cleveland Library Book No: R000040114 Classification: 942.854, Book No:

R000040114, John Farndale imagined his return to Kilton after years of

absence when he took the well known lane down

to Kilton, when at Howe Hill, and seeing a towering chimney above all; what

misgivings now trouble his unprepared, peaceful breast. But when he neared his

father’s homestead, and no place of it could be found, he moved forward, and

looking right and left, he saw some twenty cottages and farmsteads, and

behold that beautiful hall and stables that once graced this little town had

all disappeared. And he would have enquired had there not been some

eruption or some hostile invasion, or had the city not been burnt to ashes, for

said he, here are marks of violence and desperation. But “I know nobody no not

I, and nobody, nobody here cares for me,” and he lifted up

his voice and wept aloud. And he began to examine the book of records, and

genealogies of former days, days of his fathers’, and of his youth.

In A Guide

to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding District, With remarks on its

picturesque scenery, Fifth Edition, Dedicated to John Thomas Wharton Esq of

Skelton, By John

Farndale. Late of Skelton Castle Farm, Darlington, Printed by Charles W

Hird, 1864, John

Farndale wrote:

The picturesque scenery, however, in

this neighbourhood still retains its loveliness, and the late John Wharton, Esq., of Skelton Castle, did much to improve its beauty. On every side where there was any

waste land he planted it with wood to a great extent, and a

large number of larches and oaks then planted, I planted with my own

hands. On visiting this place lately, what was my astonishment on perceiving

that many of these larches were cut and measured fifty cubic feet, while the

oaks were in thriving condition and measured twenty four

cubic feet. The site of these plantations is delightful, as they are finely

sheltered from the piercing north winds.

The scenery of these woodlands, together

with the woods of Lady Downs and the Earl of Zetland, appear so truly

picturesque from Kilton height that it is utterly impossible for my pen to

describe it. Beyond these woodlands rise in view the village of Lofthouse, with

the Alum Works, and the seat of the late Sir Robert Dundas. These works are now

superintended by William Hunton Esq., an old school

fellow of mine. A little further on lies Easington and Boulby

Alum Works, conducted by G Westgarth, Esq., a gentleman

much respected. Still further, situate on the sea shore,

stands the well known fishing village of Staithes,

formerly proverbial for the roughness and rudeness of its inhabitants. Though

rough, however, they were then as they are now a hardy, kind, and hospitable

people, who obtain a living by braving the perils of the great deep. Poor Thrattles, once reckoned the King of Staithes, and who was

a good fellow, is now no more, and the place is much changed since bis days.

But the reader, perhaps may not care about lingering at Staithes, so we shall

take our stand again on Kilton How Hill, from whence may be seen the most

delightful scenery in the district.

Chapter 3 - The Farndales

of Kilton

3.1 The Farndales and Kilton

It is hard to know exactly when the

first member of the Farndale family came to Kilton. Certainly

they were there by the late seventeenth century and in the sixteenth and early

seventeenth centuries there were Farndales at Liverton, Moorsholm, Skelton and

Kirkleatham.

1705

By about 1705, Kilton was the home of

the Farndales for almost two hundred and fifty years.

In A Guide

to Saltburn by the Sea and the Surrounding District, With remarks on its

picturesque scenery, Fifth Edition, Dedicated to John Thomas Wharton Esq of

Skelton, By John

Farndale. Late of Skelton Castle Farm, Darlington, Printed by Charles W

Hird, 1864, John

Farndale wrote of the late eighteenth century: My

children’s children comprise the sixth generation of our family that has lived

at Kilton estate upwards of two hundred years.

In The

History of Kilton, With a Sketch of the Neighbouring Villages, By the Returned

Emigrant, Dedicated to the Rev William Jolley, Toronto, Canada, America,

Middlesbrough, Burnett & Hood, “Exchange” Printing Offices, 1870, Redcar

Cleveland Library Book No: R000040114 Classification: 942.854, Book No:

R000040114, John Farndale imagined his return to Kilton after years of

absence when he recalled:… The steward

always called old J Farndale to the vice-chair, he being

old, and the oldest tenant. Farndale’s was the most numerous family, and had lived on the estate for many ages…. here we have chronicled something like a

genealogy of a race of people once throng the streets of Kilton, but where are

they now to be found? Many of them have gone to their

everlasting reward, yet a few, a small few, remain unto this day.

3.2 John Farndale (FAR00116) (27 June 1680 to 5 October 1757), householder of Brotton, perhaps

the first Farndale at Kilton. The Founder of The Kilton 1 Line.

John Farndale was baptised at Liverton on 27

June 1680, the son of Nicholas and Elizabeth (nee Bennison) Farndale (FAR00082). John Farndale

married Elizabeth Bennison on 5 February 1705 at Brotton.

He was probably the first of the family

to move to Brotton, perhaps at about the time of his marriage to Elizabeth and

their family of five were born in the Parish of Brotton, probably in Kilton. He

may have been a farm labourer, of may have been a tenant farmer.

So the Farndale association with Kilton

probably started in around 1705.

John Farndale, householder was buried at

Brotton on 5 October 1757 at St Margaret Anglican Church, Brotton. He would be

77 years old (Brotton PR).

3.3 John Farndale (FAR00143) (28 February 1724 to 24 January 1807), “Old Farndale of Kilton”,

a farmer, alum house merchant, yeoman and cooper. The Kilton 1 Line.

John Farndale was baptised at Brotton on 28 February

1724, the son of John and Elizabeth Farndale (FAR00116)(BMD).

John Farndale is shown as tenant of

Cragg Farm on the Wharton Estate of 31 acres in 1773 for which he paid rent of

£26 (17s an acre).

John became a tenant

farmer at Kilton and became known as ‘Old Farndale of Kilton’.

In His Grandson’s

Booklets, ‘A Guide to Saltburn By The

Sea’ John Farndale, his Grandson writes, ‘My

Grandfather, who was a Kiltonian, employed

many men at his alum house, and many a merry tale have I heard him tell of smugglers and their daring

adventures and hair breadth escapes.’

In his booklet , The History of Kilton’ John Farndale his Grandson

wrote, Once more I stand on Skinningrove duffy sands, where I have seen it

crowded with wood and corf rods for the North by

the said Wm and John

Farndale. But what crowds of horses, men, and waggons, when

the gin ship appeared in view. Our friends had no dealings with those

Samaritan gin runners, yet they had great dealings at Skinningrove seaport,

both in export and import, as well as supplying the hall of F Easterby Esq.,

with corn, wheat, oats, beans, butter, cheese, hams, potatoes &c, &c,

and once, a year at Christmas – they

balanced accounts, over a bottle of Hollands gin, and after eulogising each

other, the squire would rise and say, “Johnny, when you are gone, there

will never be such another Johnny Farndale”. Here lived the King’s

officer, in the high season of gin running, but I knew of few captures; he

wished to live and die in peace, and the revenue received little from his

services. Near Skinnngrove are the Lofthouse iron mines, Messrs Pearse,

lessees. Above is the grand iron bridge standing on twelve massive pillars, 178

feet high, which spans the cavern from the Kilton Estate to Liverton Estate,

the first and grandest in all England. Lofthouse, and their long famed alum

works, which has been the support of Lofthouse for ages gone, but now

discontinued. How well I remember my school days when we faced all weather

through Kilton Woods, and how I respected my masters – the Rev Wm Barrick, Mr

Wm King, the great navigator, and Captain Napper, steward to the works. The

popular Midsummer Lofthouse fair was the only fair we children were allowed to

attend.

John Farndale, of

Kilton Thorpe was buried in Brotton Old Churchyard on 27 January 1807. He was

aged 83. He had lived for 18 years after the death of his wife and outlived

four of his eight children.

3.4 William Farndale (FAR00146) (born 1725). The Founder of The Kilton 3 Line.

William Farndale was a farmer of Craggs

who may have been associated with Kilton.

3.5 John Farndale (FAR00177) (5 October 1755 to 26 October 1829. The Kilton 3 Line.

John Farndale was baptised at Brotton on

5 October 1755, the son of William and Mary Farndale (FAR00146). He

married Hannah Wilson in 1787. By 1794, John was farming in Kilton.

The Skelton Estate Account for

the half Year ending Michaelmas 1820 states; Freeholders Tithes - Brotton;

John Farndale (FAR00177): One

Year due £2 7s 0d. Paid. Tenants Names: William Farndale (FAR00183): Half Year due £225

0s 0d. Paid. Tenants of Kilton; John Farndale (FAR00167), Arrears due Lady day 1820 £19. Half Year due Michaelmas 1820 £59 10s.

Received £65 10s. Arrears due, Michaelmas 1820 - £14 0s 0d. William Farndale,

Half Yearly due Michaelmas 1820 - £165 0s 0d, Paid.

John Farndale of Brotton aged 73 was

buried on 26 October 1829.

3.6 John Farndale of Kilton (FAR00167) (24 March 1750 to 23 October 1825). The Kilton 1 Line.

John Farndale was baptised at Brotton on 24

March 1750, the son of John and Grace Farndale (FAR00143).

John Farndale and Jane Pybus were

married at Skelton, by Banns, on 23 December.

The Skelton and Kilton

Terrier in 1809 provided a detailed record of John’s tenanted farm.

A ‘terrier’ is a record of field names,

with reference number, land use, acreage, value per acre and rent.

John Farndale, Tenant:

|

No |

Enclosure Name |

State in 1809 |

Quantity in a, r and p |

|

|

|

70 |

Stack Yard &c |

Pasture |

“, 2, 16 |

um |

“ 10 “ |

|

264 |

Broad Garth |

Pasture |

3, “, 32 |

an |

7 4 “ |

|

54 |

Farndale Barf |

Llea? Mea? |

2, 3, 20 |

ud |

5 3 6 |

|

71 |

Bulmer Barf |

Paddock |

4, 3, 08 |

uh |

9 2 5 |

|

72 |

do |

Fall |

4, 2, 24 |

ao |

9 15 3 |

|

95 |

Swales Barf |

Llea? Mea? |

2, “, 32 |

uh |

4 3 7 |

|

197 |

Ward Barf |

Pasture |

5, “, 24 |

uh |

9 15 8 |

|

89 |

South Cow Pasture |

Oats |

7, 1, “ |

ud |

13 1 “ |

|

90 |

North Cow Pasture |

Wheat |

4, 1, 08 |

ua |

7 6 2 |

|

55 |

Chapel Long Close |

Llea? Mea? |

4, 3, 08 |

ua |

8 3 2 |

|

53 |

Lane from Kilton to Kilton Thorpe |

Pasture |

3, 1, “ |

- |

|

|

Total |

|

|

43, “, 12 |

|

74 12 9 |

John Farndale died on 23 October 1825

aged 75 years.

3.7 William Farndale (FAR00183) (30 March 1760 to 5 March 1846). The Kilton 1 Line.

William Farndale was baptised

at Brotton on

30 March 1760, the son of John & Grace Farndale (FAR00143) (BMD). He married Mary Ferguson at Brotton on 20

September 1789.

From the

writings of John Farndale his son wrote in ‘Kilton,

this Ancient Hamlet of Old.; ‘….. And

now we come to our grandfather’s and father and mother, William and Mary

Farndale, and their seven children’s birth place;

farmers and merchants of wood, rods, coals, salting

bacon; church people. And those premises are held by our youngest brother,

held from generation to generation this two hundred years.

Springing from this roof may be said to

be forty Farndales of this last generation…..’

William Farndale pulled down the old Kilton Lodge,