|

|

The Poachers of Pickering Forest

Some Farndales are referred to as Yeoman

|

|

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Context and local history are in purple.

This page has the following sections:

·

The

Farndales who poached in Pickering Forest and other

places

·

Terminology

of the forest

·

The

Poachers of Pickering Forest

·

Poaching

in later times

·

Links,

texts and books

The Farndales who poached in Pickering Forest and other places

1128

Henry I decreed that a huge area from

York to the coast, including Ryedale and Pickering, should be reserved as Royal

Forest, where hart, hind, wild boar and hawk were preserved solely for the

King. Officers were appointed to guard the royal forests and new administrators

were appointed such as the fee foresters and serjeantes. Some of these officers

were able to held their land rent free in return for the service as a forester.

When Henry I established the Forest of Pickering as a deer preserve he gave Guy

the Hunter half the Aislaby estate, in return for training a royal hound.

Legend claims that two brothers were given a falcon’s flight of land, for

repelling a Scots invasion. Perhaps the other brother was William of Aislaby,

who had the other half.

Serious punishments were dealt to those

who committed hunting offences, including the removal of body parts for taking

of deer.

Roger de

Stuteville was licensed to have hounds for taking wolf and hare throughout

Yorkshire and Northumberland. The Mowbrays

at Kirkbymoorside had similar privileges.

Walter Aspec in Ryedale forest gave

three deer a year as a tithe to Kirkham Priory.

1184

Old forest customs were codified in the

Assize of the Forest in 1184. Under the Norman kings, the royal forest grew

steadily, probably reaching its greatest extent under Henry II when around 30

per cent of the country was set aside for royal sport. The object of the forest

laws was the protection of ‘the beasts of the forest’ (red, roe, and fallow

deer, and wild boar) and the trees and undergrowth which afforded them shelter.

The definitive form to forest law occurred during Henry II's reign, most notably

in the Assize of the Forest (also known as the Assize of Woodstock) in 1184.

None could carry bows and arrows in the royal forest, and dogs had to have

their toes clipped to prevent them pursuing game. Savage penalties for any

infringements were often imposed. Discontent with the laws ensured that the

forest became a major political issue in John's reign. It culminated in the

Charter of the Forest (1217), but only in the 14th cent., when large areas were

disafforested, did the political issue subside.

Regarders and agisters were appointed to

guard the royal deer.

Customary

rights to timber were to be overseen by the supervision of forest officers.

These rights came to be written as forest organisation became more elaborate.

The right to wood was referred to as bote. Pickering folk could use green or

dray wood for housebote, dry wood for firebote, or haybote

for fencing. (John Rushton,

The History of Ryedale, 2003, 80).

Ownership of large dogs was controlled.

Forest offences were numerous. Many saw

poaching as a pastime. The nobility took to hunting for sport, whilst more

ordinary folk included parties from Farndale. Officials of Pickering forest

used offences to raise income, or raised funds from such as pannage payments

for pigs taken into the woods. (John Rushton, The

History of Ryedale, 2003, 125).

The Black Prince ordered his keeper of

the Farndale wood to deliver a single oak, suitable for shingles, for the

roofing of Gillamoor chapel.

1210

King John needed funds to pay for his

wars in France. He sold off many of the royal forests and there was significant

disafforestation in Ryedale.

The remaining forests were Galtres

Forest, though reduced in size, Pickering Forest

and the small forest of Farndale. Even

within Pickering Forests parks were allowed for leading nobility.

(John Rushton, The History of Ryedale, 2003, 78).

1280

Alan

Farndale (FAR00011), the son of Nicholas

Farndale (FAR00006), paid taxes to the Eyre Court in 1280. This tax might have been

bail for a poaching incident – see below. (Feet of Fines). Nicholas Farndale (FAR00006)

is the first person who used the Farndale name to describe himself.

William

the Smith of Farndale (FAR00009),

paid taxes to the Eyre Court in 1280

(this tax might have been bail for a poaching incident – see below) (Feet of Fines).

In

the same year, 1280, five Farndales were indicted for poaching and paid bail - From

sureties of persons indicted for poaching and for not producing persons so

indicted on the first day of the Eyre Court in accordance with the

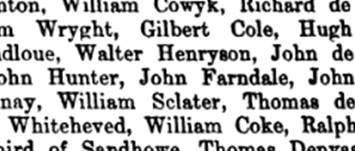

suretieship due to Richard Drye. There follows a long list of names

including,…..1s 8d from Roger son of Gilbert of Farndale

(FAR00028), bail from Nicholas de Farndale, (FAR00022),

2s from William the Smith of Farndale (FAR00009),

3s 4d from John the shepherd of Farndale, (FAR00010),

and 3s 4d from Alan the son of Nicholas de Farndale. (FAR00011) (Yorkshire Fees). (See FAR0019).

1293

Peter

de Farndale (FAR00008)’s

son Robert (see FAR00012)

was fined at Pickering

Castle

in 1293 and Roger milne (“miller”) of Farndale, also a

son of Peter slew a soar in the forest in 1293.

Roger

milne (“miller”) of Farndale (FAR00013A),

son of Peter (FAR00008)

below together with Walter Blackhous and Ralph Helved, all of Spaunton on

Monday in January 1293, killed a soar and slew a hart with bows and arrows at

some unknown place in the forest. All outlawed on 5th April 1293.

1310

In 1310, Nicholas de Harland

of Farndale was fined because his cattle had strayed in the forest (North Riding records).

1316

Richard

de Farndale (FAR00016) and Thomas of Farndale (FAR00023), excommunicated for stealing on 12

August 1316. (Patent Rolls). This relates to Pickering Castle and may have arisen from an

earlier poaching incident.

Thomas and

Richard of Farndale (FAR00016), excommunicated for stealing at Pickering Castle on 12 Aug 1316.

Sentence of Excommunication; ‘To the Most Serene Prince,

his Lord Edward by the Grace of God, King of England, illustrious Lord of

Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine, his humble and devoted clerks, the Reverend Dean

and Chapter of the Church of St Peter, York; custodians of the spiritualities

of the Archbishopric while the See is vacant; Greetings to him to serve whom is

to reign for ever. We make known to your Royal Excellency by these presents

that John de Carter, William of Elington, Adam of Killeburn, John Porter, Hugh

Fullo, Peter Fullo, John of Halmby, Adam Playceman, John Foghill, Thomas

Thoyman, Robert the Miller, Adam of the Kitchen, Richard Mereschall, John

Gomodman, John Wallefrere, Alan Gage, Henry Cucte, Nicholas of the Stable, John

the baker, Adam of Craven, John son of Imanye, Michael of Cokewald, Thomas of

Morton, John of Westmerland, Thomas of Bradeford, Adam of Craven, John of

Mittelhaue, John called Lamb, William Cowherd, Simon of Plabay, William the

Oxherd, Henry of Rossedale, John of Carlton, Peter of Boldeby, Thomas of

Redmere, Walter of Boys, William of Fairland, John of Skalton, John of Thufden,

Henry the Shepherd’s boy, John of Foxton, Thomas of Farndale, John of

Ampleford, John Boost, Roger of Kerby, John of Stybbyng, William of Carlton,

Richard of Kilburn, Adam Scot, Peter of Gilling, John of Skalton, Stephen of

Skalton, Richard of Farndale, Richard of Malthous, John the Oxherd,

Robert of Rypon, Walter of Fyssheburn, Adam of Oswadkyrke, William of Everley,

Hugh of Salton, William Robley, William of Kilburn, Geoffrey the Gaythirde,

John of the Loge, Robert of Faldington, Nicholas of Wasse, William of Eversley,

Robert of Habym, John of Baggeby and William Boost, our Parishioners, by reason

of their contumacy and offence were bound in our authority by sentence of

greater excommunication, and in this have remained obdurate for 40 days and

more, and have up to now continued in contempt of the authority of the

Church. Wherefore we beseech your Royal Excellency, in order that the pride

of these said rebels may be overcome, that it may please you to grant

Letters, according to previous meritorious and pious custom of your Realm, so

that the Mother Church may, in this matter, be supported by the power of Your

Majesty. May God preserve you for His Church and people.’

Given at York 12 August 1316.

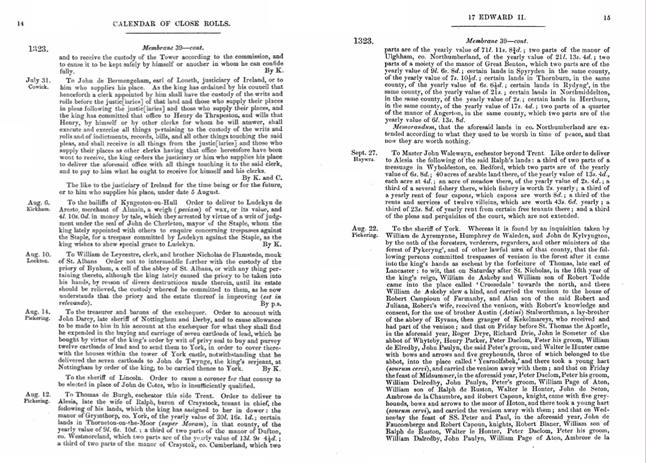

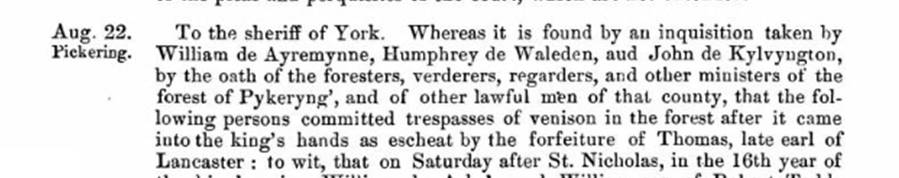

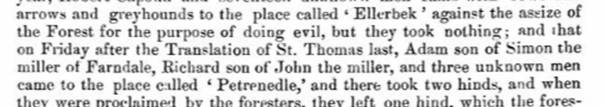

In

the Calendar of the Close Rolls, 22 August 1323:

Pickering. To the sheriff of York. Whereas it is found by an inquisition taken

by William de Ayremynne, Humphrey de Waleden, and John de Kylvyngton, by the

oath of the foresters, verderers, regarders, and other ministers at the forest

of Pickering, and of other lawful men of that county, that the following

persons committed trespass of venison in the forest after it came into the

King's hands as escheat by forfeiture of Thomas, late earl of Lancaster... that

on Friday the morrow of Martinmas, in the aforesaid year, Robert Capoun,

knight, Robert son of Marmaduke de Tweng, and eight unknown men with bows and

arrows and four greyhounds came to a place called ‘Ellerbek’, and there took a

hart and two other deers (feras), and carried the venison away; and that on

Thursday before the Invention of the Holy Cross, in the aforesaid year, Robert

Capoun and seventeen unknown men came with bows and arrows and greyhounds to

the place called ‘Ellerbek’ against the assize of the forest for the purpose of

doing evil, but they took nothing; and that on Friday after the Translation of

Saint Thomas last, Adam (FAR00025) son of Simon the Miller of Farndale,

Richard son of John the Miller, and three unknown men came to a place called

‘Petrenedle’, and there took two hinds, and when they were proclaimed by the

foresters, they left one hind, which the foresters carried to Pykeryng castle

and the said malefactors carried the other away with them;... the King orders

the sheriff to take with him John de Rithre, and to arrest all the aforesaid

men and Juliana, and to deliver them to John de Kylvynton, keeper of Pykeryng

castle, whom the king has ordered to receive them and to keep them in prison in

the castle until further orders.

‘At Pickering before the Sheriff of York in 1323, on

Friday after the translation of St Thomas last, Adam son of Simon the miller

of Farndale, (21), Richard the son of John the miller three unknown men

came to the place ‘Petrenedle’ and there took two hinds and when they were

proclaimed by the foresters they left one hind which the foresters carried the

other way with them...(long list of other offenders)...... The King orders the

Sheriff to take with him John de Rithre and to arrest the aforesaid men and

deliver them to John de Kyltynton, Keeper of Pyckeryng

Castle whom the King ordered to receive them

and to keep them in prison until further orders.’ Was this the same Adam de Farndale,

who would be 28 at the time which would fit? (Close Rolls 22 August 1323, 17 Edward II page 15 and 16)

John

de Farndale (FAR00026) was released from excommunication at

Pickering Castle on 23 February 1324. This may have related to a prior poaching

offence. Text of Release From Excommunication; ‘To the Most Serene Prince, His Lord Edward, by the Grace of God, King

of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine, William by Divine

permission Archbishop of York, Primate of England, Greetings in him to serve

who is to reign for ever. We make known to Your Royal Excellency, by these

presents that William de Lede of Saxton, John of Farndale and John Brand of

Howon, our Parishioners, lately at our ordinary invocation, according to the

custom of your Realm, were bound by sentence of greater excommunication and,

contemptuous of the power of the Church, were committed to Your Majesty’s Prison

for contumacy and offences punishable by imprisonment; and have humbly done

penance to God and to the Church, wherefore they have been deemed worthy to

obtain from us in legal form the benefit of absolution. May it therefore please

Your Majesty that we re-admit the said William, John and John to the bosom of

the Church as faithful members thereof and order their liberation from the said

prison. May God preserve you for His Church and the people.’ Given at

Thorpe, next York, 9 April 1324.

1330

The

date of the following extract from the Coucher Book, folio 222, is probably about

1330 :—

The Coucher Book, folio 224, tells how

two men, on Thursday next after the feast of S. Lucy the Virgin, went to

Mulfosse, in Hartoft, and there slew one hind. How

" Thomas de Hamthwaite, Robert de

Bolton, Richard of Helmsley, John de Skipton, Robert Moryng, Abraham Milner,

Stephen Moye, and Peter son of Henry, with others unknown, on Thursday, 7th of

March, 1331, went to a place called Hamclifbek, with two leporariis (gazehounds

or greyhounds), and belonging to John de Kilvington and Robert Spink, and with

bows and arrows, and there slew one soar and one hind and one stag, and were

fined, etc."

In the same folio we have an account of

how " Roger son of Emma, John de Bordesden, Robert Moryng, John son of William

Fabri (Smith) of Farndale (FAR00037), Robert Stybbing, and William Bullock,

about the feast of S. Bartholomew, captured one hind and one calf at Rotemir."

How " Hugh de Yeland and John de Yeland, Thomas Hampthwait, William de

Langwath, Peter son of Henry Young, William de Hovingham, forester of Spaunton,

William Burcy (or Curcy), Robert de Miton, sergeant of Normanby, and six others

unknown, captured at Leasehow, with bows and arrows and hounds, a young

hart," and so on.

(History of

the Parish of Lastingham)

1332

Robert

Farndale (FAR00012) son of Peter of Farndale,

fined for poaching, at Pickering

Castle

in 1332. (If 40 at the time he was born about 1292 when his father Peter (FAR00008) would be about 54).

Robert Farndale (FAR00031) son of Simon the miller of

Farndale (FAR00021), and Robert son of Peter

of Farndale, (FAR00008), were fined for poaching

at Pickering Castle in 1332 (Patent Rolls)

1334 and 1335

Nicholas of Farndale (FAR00022), gave bail for Roger son of Gilbert of

Farndale (see FAR00028) who had been caught poaching in 1334

and 1335.

‘Pleas

held at Pickering on Monday 13 Mar 1335

before Richard de Willoughby and John de Hambury. The Sheriff was ordered to

summon those named to appear this day before the Justices to satisfy the Earl

for their fines for poaching in the forest of which they were convicted

before the Justices by the evidence of the foresters, venderers and other

officers. They did not appear and the Sheriff stated that they could not be

found and are not in his bailiwick and he had no way of attacking them. He was

therefore ordered to seize them and keep them safely so that he could produce

them before the Justices on Monday 15 Mar 1335. A long list of names follows

including……Robert filium Simonis de Farndale, Rogerum de milne de

Farndale, Robertum, filium Petri de Farndale,( FAR00024)…………’ (NRRY Vol III)

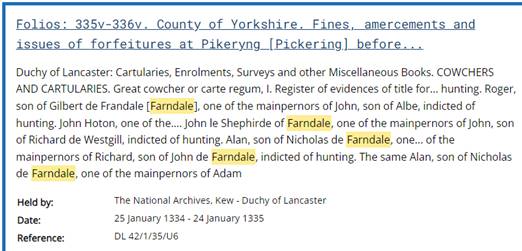

National Archives Ref DL

42/1/35/U6

1334 Jan 25-1335 Jan 24

Folios: 335v-336v. County of

Yorkshire. Fines, amercements and issues of forfeitures at Pikeryng

before

The following records

require supervised handling in Collection Care. Please contact The National

Archives to arrange viewing. Appointments are available from Tuesday to Friday

at 11.00am or 2.00pm, are limited to two hours and are subject to availability.

Folios: 335v-336v. County of

Yorkshire. Fines, amercements and issues of forfeitures at Pikeryng

[Pickering] before Richard de Wylughby [Willoughby],

Robert de Hungerford and John de Hambury, itinerant

justices assigned to take the pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of Lancaster,

of Pickering.

People mentioned: Agnes Snawe of Aslagby [Aislaby]. Nicholas Tran. Henry de Boys. Geoffrey de Chymyne. John Cawode. Robert de Grendale [Grindale]. Thomas, son

of Amicia. William, son of Alexander Tateman.

William, son of Alexander. John Thurnyf. Hugh de Shenynton. Thomas Ouhtred,

knight. John in Solar'. John de Viridi of Semere

[Seamer]. Robert Jolle. Margaret in le Loft. Margaret Nalbarn.

John Danyel [Daniel]. Robert Wawayn. Robert, son of

Alexander. Roger Pynchon. Margaret de Haterbergh.

Thomas, son of Henry. Roger, son of Ralph de Osgodby.

Thomas, nephew of the parson of Sneton Roston

[Ruston]. Roger Fallidam. William Fallidam.

The prior of Heghitldesham [Hexham]. Alexander de Westhorp [Westhorpe]. John, son of Allinet.

John, son of Geoffrey. John de Shelton. Alan Grelley.

The vills of Pikeryng

[Pickering] and Gotheland [Goathland]. The vills of Sillyngton [Sinnington]

and Marton. The vill of Aslaghby

[Aislaby]. The vill of Farmanby. Roger Drye, one of the mainpernors

of Richard Drye, indicted of hunting. Hugh Lenonus,

another mainpernor of Richard Drye, indicted of

hunting. John Whyte, another mainpernor of the said

Richard Drye, indicted of hunting. Roger de Verdale, another mainpernor of the said Richard, indicted of hunting. Alan,

son of Alexander, one of the mainpernors of William

Haye, indicted of hunting. The same Alan, son of Alexander, one of the mainpernors of Adam de Suthfeld,

indicted of hunting. Robert, son of Alexander, one of the mainpernors

of William Haye, indicted of hunting. The same Robert, son of Alexander, one of

the mainpernors of Adam de Suthfeld,

indicted of hunting. The same Robert, son of Alexander, one of the mainpernors of Richard, father of the said William Haye,

indicted of hunting. Roger de Verdale, one of the mainpernors

of William Haye, indicted of hunting. Roger de Verdale, mainpernor

of Richard, father of the said William Haye, indicted of hunting. Roger de Multhorp, one of the mainpernors

of William de Haye, indicted of hunting. Roger de Multhorp,

one of the mainpernors of Richard, father of the said

William Haye, indicted of hunting. Roger, son of Gilbert de Frandale

[Farndale], one of the mainpernors of John, son of Albe, indicted of hunting. John Hoton,

one of the mainpernors of John Albe,

indicted of hunting. Thomas Makaunt, one of the mainpernors of John, son of Albe,

indicted of hunting. Henry del Tunge, one of mainpernors of John, son of Albe,

indicted of hunting. Peter, son of Gervase, one of the mainpernors

of John, son of Albe, indicted of hunting. Ralph the

merchant of Pikeryng [Pickering], one of the mainpernors of John Cokerell,

indicted of hunting. William the smith of Cropton, one of the mainpernors of the same John Cokerell,

indicted of hunting. Robert Westgyll, another mainpernor of John, son of Richard de Westgill,

indicted of hunting. John Alberd, another mainpernor of the same Robert, son of Richard de Westgill, indicted of hunting. The same John Alberd, one of the mainpernors of

John, son of Richard de Westgill, indicted of

hunting. John, son of Walter, one of the mainpernors

of Robert, son of Richard de Westgill, indicted of

hunting. John le Shephirde of Farndale, one of the mainpernors of John, son of Richard de Westgill,

indicted of hunting. Alan, son of Nicholas de Farndale, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John de Farndale, indicted

of hunting. The same Alan, son of Nicholas de Farndale, one of the mainpernors of Adam, son of Simon the miller of Farndale,

indicted of hunting. Nicholas Laverok, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John de Farndale,

indicted of hunting. The same Nicholas Laverok,

one of the mianpernors of Adam, son of Simon the

miller, indicted of hunting. John, son of John the miller, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale,

indicted of hunting. The same John, son of John the miller, one of the mainpernors of Adam, son of Simon the miller, indicted of

hunting. William le Smyth of Farndale, one of the mainpernors

of Robert, son of Richard de Westgill, indicted

of hunting. The same William le Smyth of Farndale, one of the mainpernors of John, son of Richard de Westgill,

indicted of hunting. John, son of John the miller, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale,

indicted of hunting. The same John, son of John the miller, one of the mainpernors of Adam, son of Simon the miller, indicted of

hunting. Nicholas Brakenthwayt, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John the miller of

Farndale, indicted of hunting. The same Nicholas Brakenthwayt,

one of the mainpernors of Adam, son of Simon the

miller, indicted of hunting. Alan de Braghby, one of

the mainpernors of Richard, son of John the miller of

Farndale, indicted of hunting.

Held on: Monday next after

Michaelmas 8 Edw III.

In Latin

Not on public record.

Folios: 228-229. County of

Yorkshire. Pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of Lancaster,...

DL 42/1/23/U29

1334 Jan 25-1335 Jan 24

Folios: 228-229. County of

Yorkshire. Pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of Lancaster, of Pikeryng [Pickering], held at Pickering before Richard de Wylughby [Willoughby], Robert de Hungerford and John de Hambury, justices itinerant on

this occasion assigned to take pleas of the said forest in Yorkshire:

Trespassers of the hunt, and their mainpernors, who

were sent away and do not come:

William, son of Moyson of Dales: William was sent away by the mainprise of

William Moyson, William, son of Thomas of Hakenes [Hackness], Thomas of the

same, John de Erden of the same, John de Sneynton of

the same, Robert, son of John de Everle [Everley], Robert de Hakenes [Hackness] of Brokeseye [Broxa], Geoffrey de

Holtby of Hakeneys [Hackness]

and John Wodeman of Pikeryng

[Pickering], who mainperned to have him on the first

day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

William de la More the elder

of Ogelberdby [Ugglebarnby]:

William was sent away by the mainprise of Robert le Saler of Thornton, John de Bretteby of the same, William Itory

of the same, Roger, son of Robert de Ogwerdby [Ugglebarnby], Geoffrey, son of Rand' of the same, and

Geoffrey Hirde of the same, who mainperned to have

him on the first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

John Cokerell

of Cropton: John was sent away by the mainprise of Elias Cokerel

of Cropton, Richard atte Yate of the same, William

the smith of the same, Ranulph the merchant of Pikeryng

[Pickering], Robert Kyng of the same, William th

weaver of the same, and William the miller of Cropton, who mainperned

to have him on the first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

John Tendbarn

of Harewode [Harwood]: John was sent away by the

mainprise of William Kyng of Harwode [Harwood], Hugh Lowys of the same, William Prat, John Thurs of the same,

Roger, son of Ralph de Hakeneys [Hackness],

William the man of Lawrence of the same, Geoffrey the cook of Alverstan [Allerston], Robert Payt, William de Adel, John Scot of Pikeryng

[Pickering], Thomas de Hoton and Roger Walgh of Pikeryng [Pickering],

who mainperned to have him on the first day of the

eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

Geoffrey de Langedon: Geoffrey was sent away by the mainprise of Adam,

son of William de Kynthorp [Kingthorpe],

William son of Emma, Thomas de Hoton,

Adam Erchebaud of Pikeryng

[Pickering], William de Kernarly of the same, John de

York, John Pacok and Walter Kyng, who mainperned to have him on the first day of the eyre, and

they do not now have him, etc.

Peter Wyles: Peter was sent

away by the mainprise of William de Swynton, Geoffrey

de Eston, Robert de Heworth, Robert Forester of Egton, Robert de Wyles, and

John Cloutepotte, who mainperned

to have him, etc, and they do not now have him, etc.

Thomas Blount of Alvestan [Allerston]: Thomas was

sent away by the mainprise of Adam de Crambun of Alvestan [Allerston], Thomas de

la Chymene of Eberston [Ebberston], William Widde of the

same, Hugh Neville of Wilton, John Cok of Thornton [Thornton le Dale] and

Thomas Walker of Alvestan [Allerston],

who mainperned to have him on the first day of the

eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

John, son of Richard de Westgille of Farndale: John was sent away by the mainprise of William le Smyth of

Farndale, Richard de Westgill, John le Shephird of Farndale, John Alberd

of the same, Nicholas, son of Walter of the same, John del Heued

of the same, and Robert de Westgill, who mainperned to have him on the first day of the eyre, and

they do not now have him, etc.

Robert, son of Richard de Westgill of Farndale: Robert was sent away by the mainprise

of William le Smyth of Farndale,

John, son of Walter of the same, John Alberd of the

same, and Nicholas, son of Walter of the same, who mainperned

to have him on the first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

Roger le Carter of Scardeburgh [Scarborough]: Roger was sent away by the

mainprise of Aymer Gedge, John de Haterbergh, John de

la Chymene, Thomas Cokerell,

John son of Alan, John Cruel, John de Bulmere, John Dryng, Walter de

Holm, Thomas del Hunthous, William Haldan and Thomas

de la Chimene, who mainperned to have him on the

first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

William, son of Mariota Lyiard of Scardeburgh

[Scarborough]: William was sent away by the mainprise of Aymer Gedge, John de Haterbergh, John de la Chymene,

Thomas Cokerell, John son of Alan, John Cruel, John

de Bulmere, John Dryng,

Walter Holm, Thomas del Hunthous, William Haldan and

Thomas de la Chemene, who mainperned to have him on

the first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

William, son of Ralph the

miller: William was sent away by the mainprise of Ralph the miller of Lokton [Lockton], Roger de Lokton

[Lockton], Ralph de la Dale, Adam Blome, Alan de Wrelton,

Ralph le Colier, Nicholas de Wrelton, Simon del Hull,

Geoffrey de Dundale, Nicholas the man of Ralph, Robert de Dundale, Thomas Raven

and John Burell, who mainprised to have him on the

first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

Henry Chubbok:

After he trespassed about hunting in this forest, Henry was sent away by the

mainprise of William Haldan, William de Ugelardeby [Ugglebarnby], John Cruel, Robert de la Gayole,

William the forester of Alvestan [Allerston],

Robert de Hale, Thomas de la Chymene, Ralph Jolyve, Hugh Awerkman, Alan

Child, William Gylory and William Faireneu,

who mainperned to have him on the first day of the

eyre, and they do not now have him, etc.

John, son of Alan de

Thornton: John was sent away by the mainprise of Edmund de Hastynges

[Hastings], William de Neville, William Reynald of Pikeryng

[Pickering], Stephen Dote, Walter, son of Gocelin of Levesham [Levisham], Alan Pye the

elder, Alan, his son, Roger Brun [Brown], Alan de Neuton

[Newton], John de Hoton of Farmanby,

Richard Guer and John le Feur, who mainperned to have him, etc, and they do not now have him,

etc.

Held on: Monday next after

Michaelmas 8 Edw III.

1336

John

de Farndale (FAR00026),

bail by him for poaching, given at Pickering before Richard de Wylughby and

John de Hainbury on Monday 2 Dec 1336 (Yorkshire

Fees).

William, smith of Farndale (FAR00037),

on Monday 2 Dec 1336, came hunting in Lefebow with bow and arrows and

gazehounds………’ (NRRY Vol III).

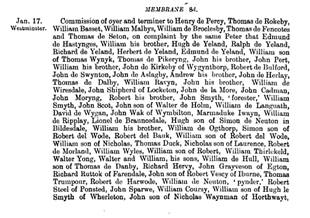

1348

From the

Calendar of Patent

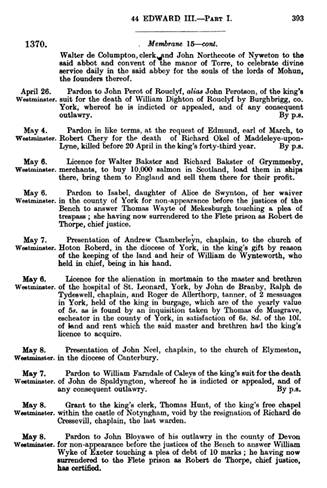

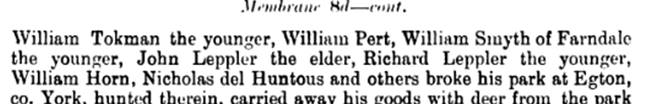

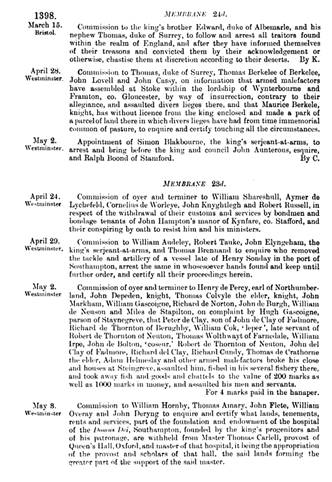

Rolls, Edward III AD 1345 to 1348, 21 Edward III – Part III, page 472: Jan 17,

Westminster. Commission of Oyer and terminer to Henry de Percy, Thomas de

Rokeby, William Basset, William Malbys, William de Broclesby, Thomas de

Fencotes and Thomas de Seton, on complaint by the same Peter that Edmund de

Hastynges …. William Smyth of Farndale the younger … broke his park at Egton,

Co York, hunted therein, carried away his goods with deer from the park and

assaulted his men and servants, whereby he lost their service for a great time.

By fine of 1 mark.

There is also a reference to Richard Ruttok of Farendale in the long list

of names.

So on 17 January 1348

at Westminster, there was a commission of oyer and terminer to a long list of

names including William Smyth of Farndale (FAR00040)

the younger and Richard Ruttok of Farendale for breaking in to the park at

Egton, hunting and carrying away the property of the owner with deer, and for

assaulting the owner’s men and servants causing their inability to work for a

long time, for which the werefined 1 mark.

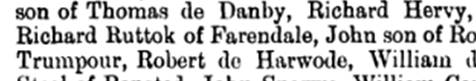

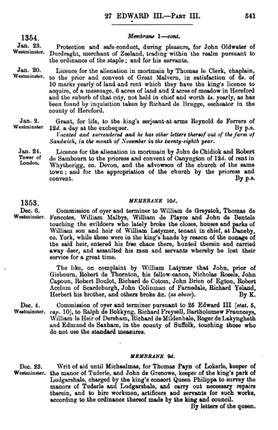

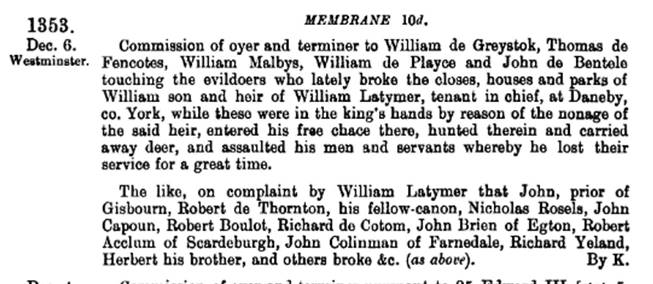

1353 and 1354

Patent Rolls, 27 Edward III Part III, page 541 and index: Commission

of oyer and terminor to William de Greystok … touching the evildoers who

latekly broke to closes, houses and parks of William son and heit of William

Latymer, tenant in chief at Daneby, co York, while these were in the king’;s

hands by reason of the nonage of the said heir, entered his free chace there, hunted

therein and carried away deer, and assulated his men and servants whereby

he lost their service for a great time. The like complaint by William Latymer that

Johbn, prior of Gisborne, Robert de Thornton, his fellow canon, Nicholas Rosels

… John Colinman of Farnedale … and others broke etc (as above) …6 December 1353 – see FAR00042.

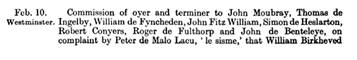

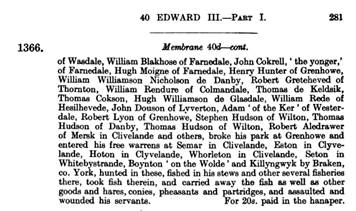

1366

William Blakhose of Farndalde, John

Cokrell the Younger of Farnedale and Hugh Moigne of Farnedale were all fined

20s for poaching fish in 1366 (Patent Rolls

40 Edward III Part 1, pages 280 to 281).

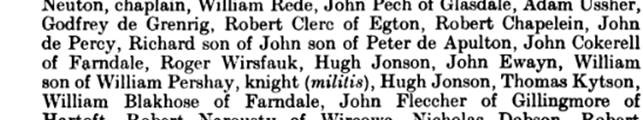

‘February

10, At Westminster. Commission of Oyer and Terminer to John Mourbray,

Thomas de Ingleby … on complaint by Peter de Malo Lacu, ‘le sisme’, that William Birkhead of

Wasdale …William Blakhose of Farndale, John Cokrell the younger of Farndale….

broke park at Grenhowe and entered his free warrens at Semar in Clyvelande,

Whorleton in Clivelande, Seton in Whitebystrande, Boynton ‘on the Wolde’ and

Killyngwyk by Braken, co York, hunted in these, fished in his stews and other

several fisheries there, took fish therein, and carried away fish as well as

other goods and hares, conies, pheasants and partridges, and assaulted and

wounded his servants. For 20s paid in the hanaper.

See FAR00047.

William Blackhous is also referred to in another incident in 1293 involving

Roger milne of Farndale( FAR0013A).

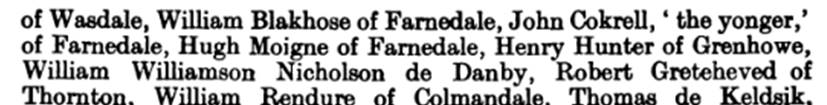

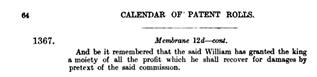

1367

Calendar

of Patent

Rolls, 41 Edward III Part II, page 63: ‘November 8, At

Westminster. Commission of Oyer and Terminer to John Mourbray, Thomas de

Ingleby … on complaint by William Latymer, knight, that whereas the king lately

took him, his men, lands, rents and possessions into his protection while he

stayed in the king’s service in the parts of Brittany, Master John de Bolton,

clerk, Thomas de Neuton, chaplain, William Rede … William of

Farndale … William Blakehose of Farndale … broke his closes at

Danby, Leverton, Thornton in Pykerynglith, Symnelyngton, Scampton, Teveryngton

and Morhous, Co York, entered his free chace at Danby and his free warren at

the remaining places, hunted therein without licence, felled his trees

there, fished in his several fishery, took away fish, trees, deer from the

chace, hares, conies, pheasants and partridges from the warren departured, trod

down and consumed the corn and grass there with certain cattle and assaulted

and wounded his men and servants. By K And be it remembered that the said

William has granted the king a moiety of all the profit which he shall recover

for damages by pretext of the said commission.

See FAR00047.

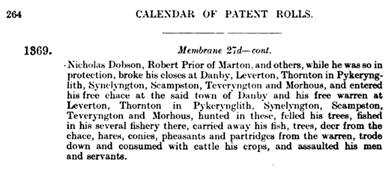

1369

Calendar

of Patent

Rolls, 43 Edward III Part I, page 263: ‘March 6, At Westminster. Commission of Oyer

and Terminer to John Mourbray, Thomas de Ingleby … on complaint by William

Latymer, knight, that whereas the king lately took him, then stayed in his

service in Brittany, and his men, lands,

rents and possessions into his protection, into his possession for a certain

time, Master John de Bolton, clerk, Thomas de Neuton, chaplain, William Rede

…John Cockerell of Farndale … William Blakhose of Farndale … broke his closes

at Danby, Leverton, Thornton in Pykerynglith, Symnelyngton, Scampton,

Teveryngton and Morhous, and entered his free chace at the said town of Danby

and his free warren at the remaining places, hunted in these, felled his

trees there, fished in his several fishery there, carried away his fish,

trees, deer from the chace, hares, conies, pheasants and partridges from the

warren, trode down and consumed with cattle his crops and assaulted his men and

servants.

See FAR00047.

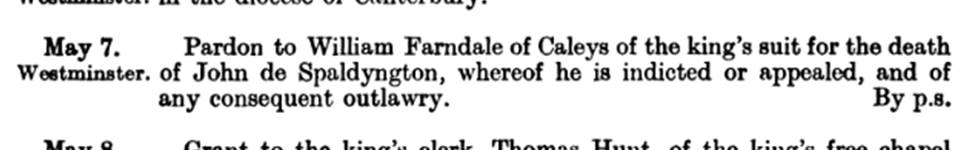

1370

7

May 1370, Westminster.

Pardon to William

Farndale (FAR00047A) of Caleys of the King's suit for the death of John de

Spaldyngton, whereof he is indicted or appealed, and of any consequent

outlawry.

(Calendar of

Patent Rolls, 44 Edward III – Part I, page 393).

1372

Calendar

of Patent

Rolls, 46 Edward III – Part II, page 243: 1372, Nov 20. Westminster.

Commission to Robert de Roos, sheriff of York, Acrise de Hanlaby, Roger de

Fulthorp, William de Nessfield, James de Raygate, John Clervaux and John de

Topclif of Rypon to arrest and commit to prison all persons prosecuting appeals

in derogation of the judgement of the justices of the Bench whereby the king

recovered against the abbey of St Mary’s York, and Richard Belle, Chaplain, his

presentation to the church of Croft, lately void and in the King’s gift by

reason of the temporalities of the abbey of St Mary, York, being in his hand,

and to the hindrance of the king’s clerk, Henry Bowet, who holds the church on

the king’s presentation.

Commission

of oyer and terminer to Ralph de Hastynges, John Moubray, Thomas de Ingleby,

Roger de Fulthorp and John de Laysyngby, on complaint by William Latymer that

John de Rungeton, John son of John Percy of Kildale, John de Grenhowe,

chaplain, John de Grenhow, parson in the church of Kildale, John Porter of

Farndale, Hugh Bailly of Farndale, Adam Bailly of Farndale, and others,

entered his free chace at Danby co York, hunted therein without licence and

took deer therefrom, and assaulted his men and servants. By C.

See FAR00048.

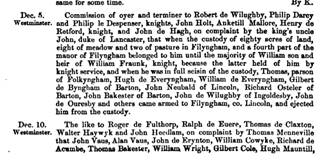

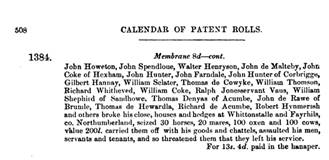

1384

On 10 Dec 1384, At

Westminster. Commission of Oyer and Terminer. John Farndale

(FAR00042A) and others broke their close, houses and hedges at Wittonstalle

and Fayrhils, Co Northumberland and seized 30 horses, 20 mares, 100 oxen and

100 cowes valued at £200 and carried them off with goods and chattels,

assaulted his men, servants and tenants and so threatened them that they left

his service.

(Calendar of Patent Rolls)

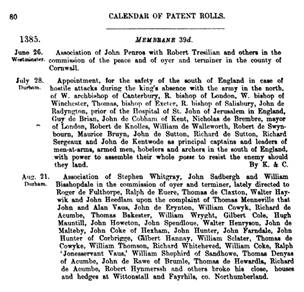

On 21 Aug 1385 at Durham.

Commission of Oyer and Terminer….John Farndale, and others broke their close,

houses and hedges at Wittonstalle and Fayrhils, Co Northumberland.’

(Calendar of Patent Rolls, 9 Richard II, page 80).

1396

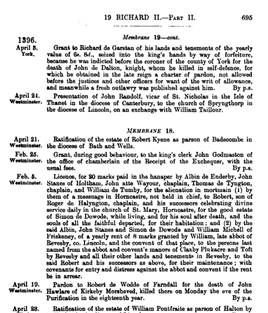

19 April 1396 - Pardon to Robert

de Wodde of Farndale (FAR00053) , for the death of John Hawlare of Kirby

Moorseved, killed there on Monday, the eve of the Purification in the 18th

year.

1398

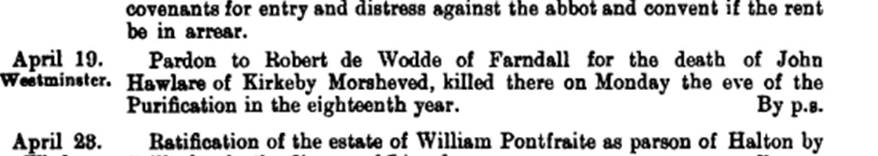

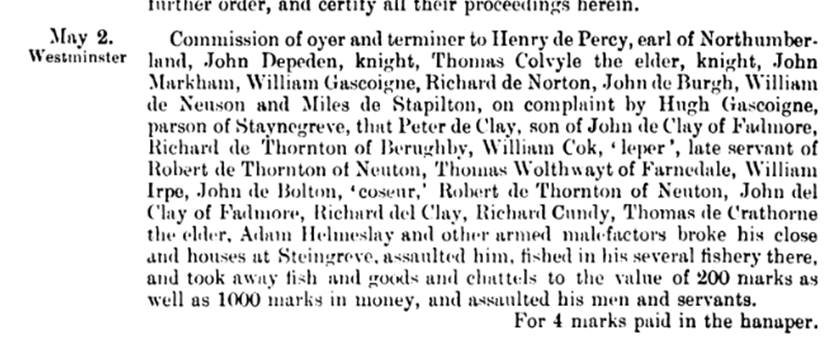

There was a

serious armed robbery. Calendar of Patent Rolls,

Richard II, 1396 to 1399, 21 Richard II Part III, 1398, page 365: ‘May

2, At Westminster. Commission of Oyer and Terminer to Henry de Percy, earl of

Northumberland, John Depeden, knight, Thomas Colvyle the elder, knight, John

Markham, William Gascoigne, Richard de Norton, John de Burgh, William de

Nenson, and Miles de Stapilton, on complaint by High Gascoigne, parson of

Staynegreve, that Peter de Clay, son of John de Clay of Fadmore, Richard de

Thornton of Neuton, Thomas Wolthwayt of Farnedale, William Irpe, John de

Bolton, ‘coseur’, Robert de Thornton of Neuton, John del Clay of Fadmore,

Richard del Clay, Richard Candy, Thomas de Crathorne the elder, Adam Helmeslay,

and other armed malefactors broke his close and houses at Steingreve, assaulted him, fished in his several fishery there, and took away his fish and goods and

chattels to the value of 200 marks as well as 1000 marks in money,

and assaulted his men and servants. For 4 marks paid in the hanaper.’ See FAR00054.

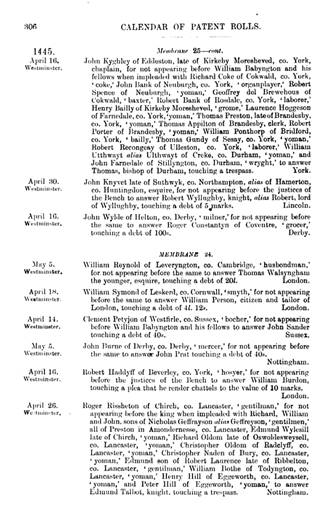

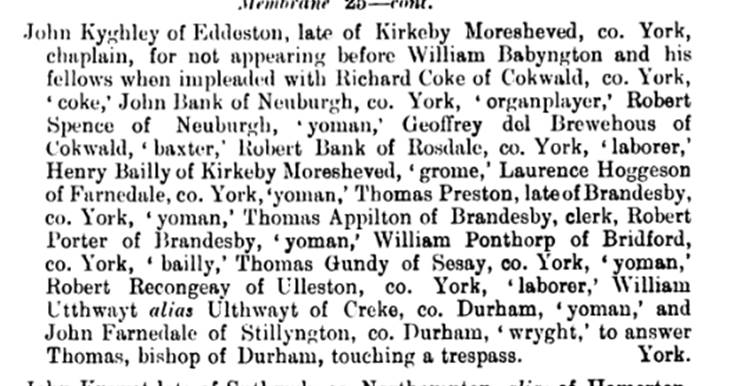

1445

On 16 April 1445 at

Westminster…..for not appearing before William

Babynton and his fellows when impleaded with Richard Coke of Cokewald, Co

York…. Lawrence Hoggeson of Farndale and John Farndale of Stillyngton Co

Durham, wright, to answer Thomas Bishop of Durham touching trespass.

Terminology of the Forest

Verderers were forestry officials in England who

deal with common land in certain former royal hunting areas which are the

property of the Crown. The office was developed in the Middle Ages to

administer forest law on behalf of the King. Verderers investigated and

recorded minor offences such as the taking of venison and the illegal cutting

of woodland, and dealt with the day-to-day forest administration. Verderers are

still to be found in the New Forest, the Forest of Dean, and Epping Forest,

where they serve to protect commoning practices, and conserve the traditional

landscape and wildlife. Verderers were originally part of the ancient judicial

and administrative hierarchy of the vast areas of English forests and Royal

Forests set aside by William the Conqueror for hunting. The title Verderer

comes from the Norman word ‘vert’ meaning green and referring to

woodland. These forests were divided into provinces each having a Chief Justice

who travelled around on circuit dealing with the more serious offences. Verderers

investigated and recorded minor offences and dealt with the day to day forest

administration.

Regarders were generally knights sworn to carry

out the regard of the Forest, which preceded the eyre. In old English law, they were

ancient officers of the forest whose task was to take a view of the forest

hunts.

A hart is a male red deer and

contrasts with a female hind. The word comes from the Middle English

word hert meaning deer.

The reference to a soar is

probably to a sow or female pig or boar.

The value of a mark was 13s 4d. There

is a webpage about the value of medieval money.

A website about Robin Hood provides an

interesting summary of Forest

Law.

The Poachers of Pickering Forest

The Poachers of Pickering

Forest 1282-1338 by Derek Rivard (Medieval Prosopography, Vol. 17, No. 2

(Autumn 1996), pp. 97-144 (48 pages)):

On a chilly Wednesday, 23 March 1334,

Nicholas Meynell led an expedition out upon Blakely Moor to poach the deer of

Pickering Forest. Accompanying this lord of the North Riding of Yorkshire was a

band of at least forty men and boys, including tenants and under-tenants,

clergymen and knights, and even the younger Peter de Mauley, baron of Mulgrave.

Carrying bows and arrows and leading gazehounds that would track and dismember

the prey, this band of "respectable" criminals slew an astonishing forty-two

harts and hinds in the space of one day. Not content with this breach of the

forest law, the hunters left upon the moor a grisly gesture of defiance for the

foresters of Pickering: the decapitated heads of nine harts, impaled upon

stakes fixed in the ground. One can almost hear the laughter of the poachers at

their jest as they returned home to divide the spoils, but it is certain the

foresters were not laughing: seven months later, the wealthy members of this

hunting party appeared before the Justices of the Forest for Yorkshire to be

amerced, while those among them too poor, or unwilling, to stand before the

court were outlawed.

This incident, drawn from the records of

the 1334 forest eyre, is an important event in the history of Pickering Forest,

a north Yorkshire possession of the earldom of Lancaster since Henry Ill's

reign.1 Although the magnitude of this offense is out of all proportion to the

average poaching case, the incident can nevertheless serve to illustrate

important realities of poaching in the regions marked off as being under the

jurisdiction of the prerogative forest law. The social profile of poachers cut

across lines of status, occupation, and sex. There were elements of both sport

and subsistence involved in poaching, while the hunt could also serve as an

outlet for social tensions. Poaching could bring serious penalties upon the

heads of the guilty; the existing records may thus reveal details of social and

economic standing.

Although it was an important economic

and social activity of the communities within the bounds of the forest,

poaching has been neglected by modern historians of the forest. Few studies

provide data on the identities and motivations of poachers. This present

article will trace the social and economic profile, on an individual and

corporate basis, of the poachers of Pickering Forest as found in records of the

1334 eyre. Through an examination of the eyre records, the North Riding lay

subsidies of 1301, 1327 and 1332, feudal inquisitions into knights' fees,

the calendars of letters patent and close, inquisitions post mortem, and other

sources, a quantitative and prosopographical methodology can be used to trace

the identities of these criminals. The poachers of North Yorkshire who emerge

from this study are a group characterized by diversity, arising partly from

families of local gentry but primarily from the near-anonymous men of the soil

who entered the forest as lowly interlopers intent on filling their bellies

with Lancastrian (sic, recte Yorkshire?) deer.

Hunting the elusive stag was an integral

part of the lives, consciousness, and literature of the high and late Middle Ages.

Handbooks for both the ritual and practical conduct of a hunt were

composed by members of the elite ranks of society, while lyrical and epic

poetry was composed to describe the chase, which was likened to martial

training, the quest for spiritual perfection, and the pursuit of a courtly

lover. For men and women of the lower social orders the hunt of a deer had a

more sinister aspect, as it was a breach of a complex prerogative law. Deer and

lesser animals within the bounds of designated areas (royal forests) were

protected under this law so that the unsanctioned killing of a beast could cost

the hunter a substantial fine. The fear and suspicion this law engendered

among the populace characterized the issue surrounding these protected

woodlands throughout the later Middle Ages, during which regulation was

expanded and enforced through the perambulation of eyre courts and

the creation of a complex hierarchy of forest officials. Forbidden to

attack game that could freely eat their crops, required to mutilate their dogs

to keep them from hunting within the forests, forbidden even to carry a bow

within the forest, the commoners of this era found that "hunting became

associated with freedom, feasting, and rebellion against the authorities.” By

poaching, the gentry and commoners of Pickering expressed their hatred of the

forest law, their love of sport, and their need for security in times of hardship.

The locale of this particular group of

poachers, Pickering Forest, was a northerly forest remarkable for the extent

of its woodland. For 1086, Domesday Book records the manor of Pickering as

possessing woodland sixteen leagues long by four leagues wide, covering

all of the soke of Pickering. By 1168 the formation of the honour of Pickering

from the manors of Pickering and Falsgrave (encompassing at that time the

parishes of Hackness and Scarborough) had joined the eastern forest of Scalby

(three leagues long by two leagues wide) to Pickering Forest, creating woodland

extending from the river Severn to the sea. The west ward, embracing the

original forest of Pickering, bordered the forest of Spaunton, which was in the

custody of St. Mary's Abbey, York; the east ward, Scalby, bordered on the

forest of Whitby, which in 1086 embraced over twenty-three square leagues of

forest in the parishes of Whitby, Sneaton, and Hackness, overseen by the

verderers of Whitby Abbey. The majority of this land was forested, and it

ranged from the rich vale of Pickering in the south of that parish to the high

moorlands of northern areas such as Goathland, suitable mainly for sheep

grazing.

At the time of the eyre in question, Pickering

and its forest were in the possession of Henry, third earl of Lancaster. Once

belonging to Simon de Montfort, the honor, castle, manor, and forest of

Pickering had been given in fee by Henry III to his younger son, Edmund, in

1267, the first earl of Lancaster. Edmund's son Thomas led the rebellion

against Edward II, and following Thomas's execution at Pontefract, Pickering

and its adjoining territories were confiscated by the crown. The forest and its

appurtenances were not restored to Thomas's brother Henry until the ascension

of Edward III. Besides Henry and his various under-tenants, local landholders

included Rievaulx Abbey, the Gilbertine houses of Maltón and Ellerton Priory,

and the Hospitallers, who held lands in the forest confiscated from the

Templars. When the 1334 eyre was called, Henry enjoyed the privilege (first

granted in 1285 by Edward I) of appointing his own justices and collecting the

fines and ransoms gathered there for his own use. In this sense Pickering was a

private forest, but the justices of Lancaster were still compelled to enforce

the crown's forest law; and the pervasive hatred of the forest law manifested

itself in poaching in the same manner as occurred throughout the crown forests

of southern England.

In order to identify the poachers in

their social and economic context, this study draws heavily on a

prosopographical methodology and a database that contains records selected from

a wide variety of sources. From 509 appearances in the eyre records, 399

individuals have been identified, 365 poachers and thirty-four receivers of

venison. The cases studied here occurred between 1282 and the

close of the eyre in 1338, a breadth of time that allows us to examine the

patterns of poaching throughout a turbulent period of English, and particularly

northern English, history. A systematic analysis of poaching and poachers

reveals distinct patterns of activity and three subgroups of poachers: the

elite poachers (including the peerage and greater gentry), the middling

poachers (including the lesser clergy, servants of clergymen, most forest

officers, the lesser gentry, artisans and tradesmen, urban poachers, and

receivers), and the largest subgroup, the lowly poachers (the peasantry). In

her study on Midland poachers Jean Birrell commented that the evidence of

poaching from the eyre rolls "does not lend itself to precise

statistics," but the wealth of material present in the records of

Pickering begs for a quantitative analysis, one that addresses both the numbers

and the character of each of these subgroups of poachers.

Elite poachers formed an extremely small percentage of

the entire corpus of Pickering Forest criminals. In her study of Midland

poaching Birrell has claimed that most poachers were of gentry status or

better, including within their ranks many of the knightly class,16 but this

present study has uncovered only twelve poachers who may confidently be

identified as knights. Peter de Mauley, fourth baron of Mulgrave, was with Lord

Meynell in that notorious hunting party discussed above. As a member of the

peerage and the scion of one of the two great families within the North Riding,

Peter cut an impressive figure; he inherited his father's lands in 1309 (an

estate that embraced at least six knights' fees, four capital messuages, three

parks, and the castle and orchard of Mulgrave). A pardoned supporter of Thomas,

earl of Lancaster, Peter hunted often.20 His expeditions all seem to have been

large, social gatherings, for we find him in the company of "many others

unknown” taking two harts in Wheeldale Rigg - a hunt sporting enough to allow

one hart to be completely devoured by Peter's eager gazehounds.

Another socially prominent poacher was

Sir John Fauconberg, a knight whose taste for Lancastrian (sic, recte

Yorkshire?) deer unfortunately became entwined with the greedy enmity of Edward

II's favorite. Having taken three deer within the forest of Pickering and the

woodlands of Whitby in 1323 Sir John was arrested by Hugh Dispenser junior,

imprisoned, and fined an outrageous £66 13s.4d. for his offense. In prison, he

appealed to the king's mercy and was released after paying but one-tenth of the

fine.23 Sir John's luck went only so far, for upon his arraignment in 1334 for

the third hind taken in that past expedition, he was committed to prison yet

again, a fine state of affairs for a respectable lord of three manors.

Knights presented for hunting in Pickering

Forest often hunted in poaching parties. Edmund Hastings, who held four

oxgangs in Roxby and the forestership of Parnell de Kingthorpe in 1334, went

out with members of his household and hunted a hart on Midsummer Eve, perhaps

to provide the maikn course of a seasonal feat. He was caught in the act and

forced to present a letter of pardon from the late Earl Thomas to secure his

release.26 Sir John Percy and his brother Sir William, heirs of the Percy

family of Kildale, a cadet branch of the powerful Percys

Northumberland, were also present in the

expedition of Lord Meynell and the baron of Mulgrave, for which they suffered

the indignity of being imprisoned and ransomed for £2.27 Sir Thomas of Bolton,

lord of the manors of Hutton-upon-Derwent and Hinderskelfe, went poaching with

a large party of the gentry and hounds and downed two hinds.28 Any punishment

he received has vanished from the records.

The greater gentry's role in poaching

was similar in scope to that of the knightly and baronial hunters. The gentry

as a whole was a nebulous, diverse body of individuals hovering somewhere

between peasantry and knighthood. The lack of solid data on many Pickering

individuals makes absolute categories of "greater" and

"lesser" gentry problematical; for this study, those possessing the

title dominus or domina in the records have been classified as

…

An examination of the lay subsidies

shows that only a small fraction of the poachers ever appeared to have had

adequate wealth to tax. Of the 365 poachers presented by the eyre, only 11

percent (forty-two) paid the taxes in any of these three years. This figure

falls well below Dyer's

standardized figure of 40 percent and

suggests that the majority of Pickering poachers were too poor to pay the

tax. Indeed, the vast majority of assessed poachers possessed goods valued

at £3 or less.65 This figure assumes significance when one remembers two

points: one, that the crown had, as early as 1300, set the minimum income

necessary for knightly status, the distraint of knighthood, at £40 of landed

income; and two, that for the majority of the English population of this era,

an income of £10 yearly may safely be taken as the benchmark of wealth.

Although it is not possible to gauge with certainty how much the fluctuating

valuations of movable property reflected the landed wealth of the poachers, the

small amount of goods they possessed (with £3 or less being less than 10

percent of the yearly income of £40 required by the distraint, and less than a

third of the basic income of wealthy household) suggests that all but the

richest poachers remained not too distant from a very modest standard of living.

The elites figure heavily in this small minority of criminals, however: seven

knights and five lords paid 31 percent of the total of assessed poachers Table

1 indicates the breakdown of assessed wealth for poachers, and of these the

elites fill all the movable-wealth slots of 100s. and above, as well six of the

nine slots for 60-99s. wealth. The economic standing of poachers can also be

deduced from the fines they paid for their illegal activities. Of the 365

individuals cited in the court records, 143 paid a fine to the eyre … an

examination of the fines levied reveals there was a definite tendency

towards standardised fines: the sums of a half mark (6s 8d), mark (13s 4d), and

pound (20s) were extremely common …

Wealth of Poachers Assessed in the Lay

Subsidy 1301-32

Assessed Wealth No. Poachers % All Assessed

Less than 20s. 3 7

20-59s 24 57

60-99s 9 21

100-200s 4 10

Over 200s 2 5

Total

42 100

Source : Turton, Pickering

… The artisans and other tradesmen

(urban and otherwise) show a pattern of family poaching similar to that

of the elite gentry. William and Roger Carter, accompanied by Gascon militiamen

from Scarborough Castle, hunted hares. Other urban artisans from Scarborough

were not immune to the allure of free venison, as we may see by the indictment

of Thomas Cobbler of Scarborough and several others others for the wounding of

a deer, the ill-equipped urban residents relying only on bows and a single

beagle. William Cooper of Scarborough and his apprentice also ventured several

miles into the forest in 1307, taking a stag for their friend William Russell,

who provided the hounds for the hunt and hosted the feast. Hugh the Barker, of

Whitby, hunted a deer in Ellerbeck and was outlawed for his pains; Adam the

Spicer was indicted for hunting in the company of Nicholas Hastings in 1305 and

for the shooting of two deer-calves that the foresters managed to rescue for

the table of Pickering Castle.75 Millers, smiths, and another cooper round out

this small group of poachers, none of whom appear in the lay subsidies, which

fact suggests that they were townsmen of humble standing. Only three managed to

pay fines to the eyre, one of 26s. 8d., one at 13s.4d., and the other of 10s.

Despite these few example of large fines, one is left with an overall

impression that the poachers from towns were of modest means.

The poacher-receivers and lesser gentry were of slightly

firmer economic standing in their communities than the artisans and tradesmen.

Receivers who also poached such as Thomas the Salter, often paid for their

second-hand crime with significant fines, such as Thomas's 13s.4d., or John

Chaplain of Hackness's 26s.8d.76 Lesser gentry, like John Bordesden, paid

similar fines: 10s. in John's case, or the 13s.4d. of John of Speton. Others,

such as William Freeman, were outlawed for their nonappearance …

… Forest officials, especially the

lower-class foresters and woodwards, are confirmed in their reputation for

corruption by their frequent appearances as poachers. We have already seen

several prominent individuals who, through a close reading of available

records, emerge as both poachers and officers: William Vescey, a justice of the

forest; William Latimer, who held the officer of verderer at the time of the

eyre; even the Warden of the Forest, Ralph Hastings, not without reproach when

poaching was the issue. Below these prominent men fall the majority of the

poaching officers, twenty-two men (6 percent of all poachers) employed by the

earl, local lords, or the commons to preserve a resource they themselves

regularly exploited.

Two foresters-turned-poachers were

foresters of the abbot of Rievaulx, and both acquired the unwelcome epithet "confirmed

poacher." Birrell has noted that in the Midlands those who earned this

sobriquet seem to have made their livelihood by poaching, hunting alone or in

groups, and thus were regularly brought before the justices. The frequency with

which the epithet appears in the records of poaching officers suggests that many

officers profited from exploiting both their commoner neighbours and the deer

in their charge. The foresters John Gosnargh and Walter Smith were both

branded "common poachers" and accused of sending venison to John

Wintringham, a monk of Whitby. Besides these cases of habitual offenders, there

were other officers who took advantage of their privileged position. Richard

the Forester accompanied Sir John Fauconberg’s party of 1322, in the hunt that

ended with Sir John being burdened by an extortionate fine demanded by Hugh

Dispenser; only through a payment by Sir John did Richard win a pardon and

escape imprisonment.89 Ingram the Forester found himself arraigned for an

incident in which he resorted to using an ax to slay a young doe but succeeded

only in maiming it, until his dog could track it to the ditch where the deer

expired. The activities of these men, along with their more prominent

counterparts, demonstrate that a severe abuse of power was taking place in

Pickering Forest Although these officers' fines tended to be higher than those

for common poachers, that foresters were conspicuously absent from the lay

subsidies indicates that any recompense they might have had from their

employment must have been small. Although these men enjoyed a salary, and

perhaps the fruits of extorting commoners, it seems likely that their

continuous record of poaching reflects the desire of a common man to

supplement lower-class, meager diet with meat at least as much as it

reflects a simple desire for sport and thrills …

The remaining poachers of Pickering,

those of lowly standing, form the largest single group. Of the 365, 80 percent (293) of

poachers fall into this class, the great majority of them leaving no records

save their appearances in the eyre rolls. The only identifiable group are the

garciones, lowly servant boys who led the hounds in the hunts of the gentry.

John Pauling, the lad of Peter Acklam took part in the hunt of a deer on

Yarnolfbeck in 1322 and of another on Hutton Moor in 1323. Nicholas of

Levisham, lad of Geoffrey of Everley, poached with his master and helped slay

three harts and three hinds in Thrush Fen on the Monday before Whitsunday, no

doubt to provide food for his master's holiday table. Thomas FitzAubrey was

part of an expedition in 1311 that missed its quarry yet was seized by the

foresters and had numerous possessions confiscated.103 In all save one of the

cases involving these twelve garciones, the poaching boy was outlawed. It would

seem that loyal service to a local lord did not save these lowly poachers from

the full penalty of the law. Since all the incidents involving servant boys

took place within twenty years of the commencement of the eyre, and since all

of these individuals may be taken to have been young at the time of offense, it

is unlikely that these outlaweries were merely the result of essoins due to

death by natural causes. Instead, it is far more probable that these boys, who

would be men in 1334, were in no position to pay the fines of the eyre and so

avoided the court where their masters might gladly ransom themselves but not

their lowly servants.

The remaining lowly poachers of

Pickering constitute a huge mass of individuals whose low socio-economic status

is apparent from the record of their fines, their absence from the lay subsidies,

and the seasonality of their poaching activities. Most poachers (61 percent)

never paid a fine to the eyre, and were outlawed. When one considers this

figure, it is important to recall the great time lag of more than thirty years

since the previous eyre; many of these non-appearances must surely have been

due to death. The high proportion nevertheless suggests that at least

significant portion of these offenders avoided the eyre for fear of a fine

that might break them. This is supported by the record of those who did pay

fines, as seen in Table above. Of the 143 poachers who paid, 61 percent

rendered fines of 1 mark or less, while a full fourth (26 percent) paid fines

of 6s.6d. or less. When we recall that the fines levied by the eyre operated on

an ability-to-pay scale, the relatively low level of those fines indicates that

most Pickering poachers possessed little wealth.

These poachers were also of such limited

means that most never appeared in either the lay subsidies or other records of

inquisitions. . Of the forty-two assessed poachers, over half (twenty-seven)

come from the ranks of the lowly poachers, and their wealth uniformly fell

below 60s. Other records of these poachers' economic standing may be found

among the inquisitions post mortem, John Kirkby's inquest into knights' fees,

and the letters close and patent. Although these data are too diverse and

detailed to be reproduced here in their entirety, some general observations are

possible.

In the larger picture of northern

agricultural life, it seems that most poachers were of low economic status.

Edward Miller in his study of northern peasant holdings has concluded that 12

percent of the population of Yorkshire could be deemed rich peasantry,

possessing holdings of over thirty acres. On the whole, this left north

Yorkshire peasants at a slight advantage in the size of their holding in

comparison to southern England. The absence of printed records of landholding

for any of these 280 anonymous poachers makes exact calculations impossible

but if one posits that the twenty-seven

peasants wealth enough to pay the subsidy fit Miller's definition of

"rich," and assuming that a definite relationship exists between

movable wealth and that universal standard of prosperity, landholding, then

only 9.6 percent of poachers can be considered to have been well endowed with

property. Thus the majority of the lowly poachers must be taken to fall

below even the standard of the relatively wealthy northern peasant. Also,

the overwhelming number of those poachers who make no appearance at all in the

subsidies strongly suggests that most were of very meager wealth, if not

actually poverty-stricken. Holding lands of comparative small size, much of

which may have been recently reclaimed from infertile moor and woodland in

the assarting boom of the thirteenth century, these poachers could easily

have felt compelled to supplement their meager produce with the venison of

Pickering. If, as Miller claims, the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century

forest dwellers of Pickering were embarked upon a "journey to the margin”

in their farming, it is quite conceivable that Lancastrian (sic, recte

Yorkshire) deer were commonly seen by the poor as a means of easing the rigors

of that journey.

The lowly economic status of most

poachers is apparent in the rise of poaching activity during periods of

hardship. A chronological analysis of the incidence of poaching between

1282 and 1338 reveals that only thirty-one years produced poaching cases for

the eyre (see Table 4), with the yearly average of such cases amounting to

approximately 14.8 for recorded years and 5.9 when all years between 1282 and

1338 are counted. Perhaps the most significant events to affect the region in

this period were the great famines of 1315-17 and 1322- 23. In these

singularly disastrous years of torrential rain and crop failure, the price of

all grains rose because of the great scarcity of wheat; a general scarcity of

across the countryside. Under such desperate conditions, one might expect to

see a dramatic rise in the number of individuals poaching for the years

1315-1317, as the humbler hunters sought to provide any sort of nourishment to

their starving households. Yet there was no such increase; indeed, there are no

recorded incidents for the year 1315, and 1316 and 1317 each saw only five

cases per year. This is understandable if one turns to the records of northern

farming, and of assarting in Pickering in particular, which reveal that the

major crop of the forest and its surrounding regions was oats. Of all the crops

affected by the rains of these two harvests, only oats flourished at anything

like the normal level of production: in the north, Bolton Priory estates in the

West Riding of Yorkshire produced 80 per-cent of their normal yield of oats in

1316 and cropped only 11.5 percent of rye and 12 percent of beans.1" A

crisis that struck primarily at the staple crops of wheat and barley although

it certainly presented difficulties, may not have provided a strong enough

incentive for northern poachers to increase their criminal activities in an

oats- and pastorally-focused area. Other hardships did produce notable

increases in poaching: the high rates of 1310-11 and 1331-32 coincided

with the poor oats harvests recorded on the estates of the bishop of

Winchester for those same years."3 This evidence suggests that there was a

definite link between poaching and the harvest when that harvest threatened the

livelihood of the farmers-cum-poachers

of Pickering.

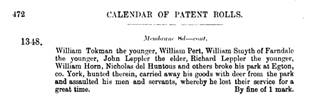

Individuals Poaching per Year in

Pickering

Year No. Persons Historical Notes

1282 5

1292 5

1293 24

1294 14

1304 5

1305 41

1306 13

1307 23

1308 6

1309 6

1311 35 poor harvest

1312 17

1313 10

1314 3

1316 5 Great Famine & murrain

1317 5 Great Famine & murrain

1321 4 famine

1322 20 famine & death of Earl

Thomas

1323 32

1324 12

1325 11

1326 3

1328 7

1329 20

1330 8 Scottish campaign begins

1331 15 poor harvest

1333 13

1334 45 beginning of eyre

1336 32 Scottish campaign ends

1337 3

1338 6

The famine year of 1321-22 also

witnessed a strong upswing in the number of cited poachers. Although the cause

of the agricultural difficulties that

provoked the famine are not known, bad weather (perhaps drought instead

of heavy rains) and the devastating sheep murrain

that struck England from 1315 to 1318 undoubtedly played a role.It is likely

that the political turbulence of the time also contributed. In 1321 there were

only four reported poachers;; in 1322, there were twenty. This increase is

explainable when one remembers that in 1322 the master

the forest, Earl Thomas of Lancaster,

was defeated at the battle of Boroughbridge, captured, and executed by Edward

II. In the same year Edward was defeated and fled before the Scots at the

battle of Byland. The death of the immediate overlord of the forest must

have provided an irresistible invitation to poachers to exploit the

unprotected deer of Pickering; indeed, a special commission was appointed by

Edward II in this year to investigate the rise in forest crime in his

newly-won, unruly territories.The defeat of the king, the nominal master of

the forest following the death of Thomas, must have only increased the

temptation to avail oneself of the deer at the expense of an absent, impotent

authority.

Political unrest may also have been

responsible for the relatively high rates of poaching in the years 1330-36 when Edward III actively pursued his

campaign against the Scots from his court at York. Hanawalt has noted the

correspondence of violent crime and the increased demand for resources caused

by political unrest, and she has especially pointed to the high incidence of

felony violence in the embattled Yorkshire of this period. It is quite possible

that the disturbances brought about by a resident army and the imminent threat

of invasion inspired an increase in the rate of poaching. Foraging soldiers and

hungry peasants alike would have sought out the deer in unstable times, when

the risk of detection might seem lessened by the presence of greater enemies

to occupy the attention of the forest authorities.

Repeated Scottish raiding on the North

Riding

throughout the last years of Edward II and the early reign of Edward III also

probably contributed to high levels of poaching. Constant raids carried off

many chattels and destroyed property, so much so that the crown in 1319

found no taxable property in 128 vills

of the North Riding. Such widespread devastation must surely have had an impact

on the high levels of poaching in the decade of the 1320s, as peasants and

lords deprived of their property took to the forest to ensure that their tables

were sufficiently provided to survive the wintry aftermath of the summer

raiding season.

Finally, the seasonality of poaching

offenses in Pickering Forest indicates that the poachers were not very much

concerned with following the recommended practice of hunting in the "time

of the grease," the season for the elite stag hunt in which the deer were

fattest, 24 June to

September. As Table 5 shows, of the 464

dateable records of poaching, only a third occurred in the optimum season of

the recreational hunt. Although these months were popular, almost equally so

were the spring months particularly March, when the first break in the upland

winter might be perceived, and May, when spring was in full bloom. These spring

months coincided with the final depletion of the poacher's winter larder, when

high grain prices and hunger could drive poachers to seek Pickering's deer.

Winter saw the least activity, because the harsh weather of the northern

winter would have impeded hunting. The overall picture is one of poaching

as a year round activity, the pattern bearing some correlation to practices of

socially-condoned hunting but more flexible in its aim of exploiting an

ever-present resource.

Poaching appears as a significant

element within the complex milieu of English forests, an activity whose appeal

was so great as to cross boundaries of status, occupation, and gender that

stratified medieval society. Poachers were an integral part of that larger

society and so reflect how the lives of medieval English men and women

intersected with the natural resources of their realm. The vast majority of

these poachers has left little trace in the records, which focus more upon the

wealthy, the powerful, the elite, than on the commoner. When we do catch

glimpses of these less powerful men and women, they are knights and minor

lords, small landholders, modest artisans and townspeople. These individuals

were of modest means, paying small fines and evading the attention of the

crown's general taxation. Less than a handful fell into what we might the ranks

of the privileged. Pursuing game in the shadow of anonymity, the majority of

these hunters from the lower classes undoubtedly sought their game for reasons

far more fundamental than the pleasure of sport or the emotional ties of

male bonding, as previous scholars have asserted. We may conclude that they

faced the penalties of the prerogative forest law for the material

security that venison provided, as a supplement and buttress to their

uncertain futures of near-poverty in times of war, famine, or disease.

Operating through ties of family, friendship, and patronage these poachers

supplied meals and camaraderie for themselves, their associates within the

community of the forest and those outsiders eager to enjoy the earl’s deer.

Fordham University

Poaching in Later Times

1720s

By the eighteenth century, on the one hand

there was a cultural emphasis on politeness and cultural achievement. On the

other hand, there was ruthless treatment of criminals and the poor.

In rural areas, there was harsh

punishment of innocuous crimes such as poaching, which in reality was a symbol

of rural inequality in times of enclosure, depriving the poor of common land

for pasture and fuel.

In London, there was organised crime.

More widely there were violent armed gangs, involved in smuggling, poaching and

housebreaking. Dick Turpin later romanticised began his criminal career as a

gang member in Essex.

Most crime however was petty.

There were few prisons or ‘police’.

Victims generally had to take matters into their own hands.

Local power

depended on deference, but by the early eighteenth century, deference had to be

earned. There was a growing confederacy between those working on the land who

increasingly saw the Squire’s property as fair booty and who colluded to help

each other against punishment. Attempts to enforce ancient Game Laws which reserved all

game to the lord of the manor, led to serious confrontation.

(Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

325-328).

Links, texts and books

The Honor and Forest of

Pickering, edited and translated by Robert B. Turton, 4 vols., North Riding

Record Society, n.s.,1-4 (1894-97), 2: 60-62.

Elizabeth C. Wright,

Common Law in the Thirteenth Century English Royal Forests [Philadelphia,

1928]).

Charles R. Young, The

Royal Forests of Medieval England (Philadelphia, 1979)

"The Forest Eyre in

England during the Thirteenth Century," American Journal of Legal History

18 [1974]:

321-31

Raymond Grant, The Royal

Forests of England (Wolfeboro Falls, 1991).

Jean Birrell, "Forest

Law and the Peasantry in the Thirteenth Century," Thirteenth Century England

II: Proceeding of the Newcastle upon Tyne Conference 1987 , ed. Peter R. Coss

and Simon D. Lloyd (Woodbridge, Suff., 1988), pp. 149-64.

"Who Poached the

King's Deer? A Study in Thirteenth Century Crime," Midland History [1982]:

9-25)

Hunters and Poachers: A Social and Cultural

History of Unlawful Hunting in England 1485-1640, Roger B. Manning, August

1993.

Forest Laws from Anglo-Saxon England to the Early

Thirteenth Century, chapter 19 of The Oxford History of the Laws of

England: 871-1216, John Hudson.