|

|

Whitby

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual history is in purple.

This

webpage about the Whitby has the

following section headings:

- Farndale

family history and Whitby

- Whitby,

overview

- Timeline of

Whitby history

- Whitby today

- Dracula

- Links, texts

and books

The Farndales of Whitby

The Whitby 1 Line are the descendants

of John Farndale,

born 1636 (FAR00087) who started a line of Farndales in Whitby by the

1660s. John was the first of the Whitby Farndales. His son Thomas Farndale,

born 1682 (FAR00118) was a carpenter in Whitby. His grandson, Francis Farndale,

born 30 September 1711 (FAR00135) was a carpenter of Whitby. His

grandson Giles

Farndale (FAR00137) served in the Royal Navy. It seems very likely that he

was press-ganged at Whitby, probably in 1740 when he would have been 27 years

old. His grandson John

Farndale, born 1711 (FAR00136) lived in Whitby and sailed with Captain

Cook and the Whitby 2 Line were

the descendants of John.

The Whitby 3 Line were the descendants

of William Farndale (FAR00157),

1743-1777, master mariner of Whitby. His son Robert Farndale (FAR00197)

1772-1796 was a ship’s carpenter.

The Whitby 4 Line were the descendants

of John Farndale (FAR00198),

born 1774, a carpenter of Whitby. His son John Farndale (FAR00244)

1802-1837 was a painter, farmer, then master mariner of Whitby. His grandson

William Farndale (FAR00289)

1825-1887 was a master mariner of Whitby whose wife Ann nee Brown ran a lodge

house. His grandson Thomas Farndale (FAR00300), born

1828 was a ship’s broker’s clerk. His grandson John Christopher Farndale (FAR00308), born

1830 was a master mariner of Whitby who later moved to Cambridgeshire.

His granddaughter Mary Ann Farndale (FAR00320), born

1822 was a shawl and bonnet maker of Whitby. The Whitby 5 Line were the descendants

of John Farndale (FAR00210),

born 1788, a farmer. His son William Farndale (FAR00257)

became an innkeeper at Egton

Many of the fifth generation of the Whitby 1 Line worked in the Flowergate area of Whitby.

Other Farndales associated with Whitby

were: Ann Farndale (FAR00100A);

Mary Farndale (FAR00142);

William Farndale (FAR00152);

Ann Farndale (FAR00165);

Hannah Farndale (FAR00174);

Elizabeth Farndale (FAR00175);

Mary Farndale (FAR00186);

Mary Farndale (FAR00190);

John Farndale (FAR00196);

William Farndale (FAR00207);

Hannah Farndale (FAR00211);

Francis Farndale (FAR00212A);

Margaret Farndale (FAR00213);

Wilson Farndale (FAR00227);

John Farndale (FAR00230);

William Farndale (FAR00243);

John Farndale (FAR00265),

a sailor of Whitby; Mary Farndale (FAR00298); Peter

Wallis Farndale (FAR00343);

Hannah Farndale (FAR00348);

Elizabeth Farndale (FAR00350A);

Mary Jane Farndale (FAR00352);

Sarah Farndale (FAR00357);

Mary Ann Farndell (FAR00359);

John Farndale (FAR00365);

Jane Ann Farndale (FAR00371);

John William Farndale (FAR00501);

Louisa Farndale (FAR00518);

Mary Farndale (FAR00526);

Sarah Ann Farndale (FAR00556);

Hannah Farndale (FAR00567);

Sarah Ann Farndale (FAR00568);

Annie Elizabeth Farndale (FAR00599);

Catherine Jane Farndale (FAR00601);

Frank Farndale (FAR00616);

Mary Alice Farndale (FAR00630);

Annie Farndale (FAR00637);

George Farndale (FAR00646A),

Served in East Yorkshire Regiment in World War 1; Ethel Farndale (FAR00658); Joseph

Salvatori Farndale; (FAR00705);

Alice Jane Farndale (FAR00753);

Doris S Farndale (FAR00789);

Violet Farndale (FAR00849);

Miriam W Farndale (FAR00905);

Jean Farndale (FAR00907);

Lydia A Farndale (FAR00991)

References to the Farndale family in Whitby baptismal registers, 1768 to 1789 include 1769 October 28th Farndale, Elizabeth (FAR00193) daughter of William and Elizabeth (sailor) born 12 October Whitby; 1772 October 26th Farndale, Robert (FAR00197) son of William and Elizabeth sailor born 11 October Whitby; 1786 February 5th Farndale, Francis (FAR00206) son of Thomas and Jane Carpenter born 3rd February Whitby ; 1786 April 18th Farndale, William (FAR00207) illegitimate son of Frances spinster born 11th April Whitby; 1788 January 27th Farndale, William (FAR00209) son of Thomas and Jane carpenter born 22 November Whitby; 1789 July 16th Farndale, Margaret (FAR00213) illegitimate daughter of Frances spinster born 2nd May Whitby.

Whitby

Whitby is a seaside

town, port and civil parish in the Scarborough

borough of North Yorkshire, England. Situated on the east coast

of Yorkshire at the mouth of the River Esk,

Whitby has a maritime, mineral and tourist heritage. Its East Cliff is home to

the ruins of Whitby Abbey, where Cædmon,

the earliest recognised English poet, lived.

The fishing port emerged

during the Middle Ages, supporting

important herring and whaling fleets, and was

where Captain Cook learned seamanship.

Tourism started in Whitby

during the Georgian period and developed with the arrival of the railway in

1839. Its attraction as a tourist destination is enhanced by the proximity of

the high ground of the North York Moors national park and the heritage

coastline and by association with the horror novel Dracula. Jet and alum were mined

locally, and Whitby Jet, which was mined by the Romans and Victorians, became

fashionable during the 19th century.

Whitby was called Streanæshalc, Streneshalc,

Streoneshalch, Streoneshalh,

and Streunes-Alae in Lindissi in records of the 7th and

8th centuries. Prestebi, meaning the

"habitation of priests" in Old Norse,

is an 11th century name. Its name was recorded as Hwitebi and Witebi, meaning the "white settlement"

in Old Norse,

in the 12th century, Whitebi in the

13th century and Qwiteby in the

14th century.

Whitby timeline

200 CE

Until recently the only

evidence of the Roman presence in this area was a soldier’s helmet and a few

coins, which were found at Guisborough and the Signal Station on Huntcliff.

656 CE

The earliest record of a

permanent settlement is in 656, when as Streanæshealh it

was the place where Oswy, the Christian king of

Northumbria, founded the first abbey, under the abbess Hilda.

A monastery was founded at Streanæshealh in

AD 657 by King Oswiu or Oswy of Northumbria, as an act of

thanksgiving, after defeating Penda, the pagan king of Mercia.

At its foundation, the abbey was an Anglo-Saxon 'double monastery' for men and

women. Its first abbess, the royal princess Hild,

was later venerated as a saint. The abbey became a centre of learning and

here Cædmon the cowherd was

"miraculously" transformed into an inspired poet whose poetry is an

example of Anglo-Saxon literature. The abbey became the leading royal

nunnery of the kingdom of Deira,

and the burial-place of its royal family.

The Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of the

County of York North Riding: Volume 2 Parishes, Whitby, 1923: The

Saxon history of the town begins with the introduction of Christianity into

Northumbria. King Edwin and his kinswoman Hilda, then a child, were baptized in

627. Edwin's successor Oswy had vowed to grant lands for monastic purposes if

he should defeat the pagan Penda, and it was possibly in connexion with his

victory at Winwaed (655) that Hilda obtained

possession of her lands at Whitby and built the monastery. Here King Edwin's

headless body, which had lain since 633 at Hatfield, was brought for burial,

and here the famous synod of 'Streoneshalch' was held

in 664.

664 CE

The Synod of

Whitby was held there in 664. The famous synod established

the Roman date of Easter in Northumbria at the expense of the Celtic one

867 CE

The monastery was

destroyed between 867 and 870 in a series of raids

by Vikings from Denmark under their

leaders Ingwar and Ubba. Its site

remained desolate for more than 200 years until after the Norman Conquest

of 1066.

The Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of the

County of York North Riding: Volume 2 Parishes, Whitby, 1923: Streoneshalch was laid waste by Danes in successive inroads

(867–70) under Ingwar and Ubba, and was said to have

remained desolate for more than 200 years ; but the existence of 'Prestebi' at the Domesday Survey may point to the revival

of religious life in Danish times. The Danish town of Whitby was presumably of

some importance, as close to it was apparently held the Danish Thing, and nearly

all the places in the district in 1086 bore Danish names. Whitby was geldable before the Conquest at the large sum of £112.

1078

Another monastery was

founded in 1078. It was in this period that the town gained its current

name, Whitby (from "white settlement" in Old Norse).

The first recorded use of the name Whitby in the eleventh century is unlikely

to have been more than a hundred or so years old, since its origin in

Scandinavian.

After the Conquest, the

area was granted to William de Percy who, in 1078 donated land to

found a Benedictine monastery dedicated to St

Peter and St Hilda.William de Percy's gift

included land for the monastery, the town and port of Whitby and St Mary's

Church and dependent chapels at Fyling, Hawsker, Sneaton, Ugglebarnby, Dunsley, and Aislaby, five

mills including Ruswarp, Hackness with two mills and two churches.

1128

In about 1128 Henry I

granted the abbey burgage in Whitby and permission to hold a fair at the

feast of St Hilda on 25 August. A second fair was held close to St Hilda's

winter feast at Martinmas. Market rights were granted to the abbey and

descended with the liberty.

1539

Whitby Abbey surrendered

in December 1539 when Henry VIII dissolved the

monasteries.

1540

In 1540 the town had

between 20 and 30 houses and a population of about

200. The burgesses, who had little independence under the abbey,

tried to obtain self-government after the dissolution of the monasteries.

The king ordered Letters Patent to be drawn up granting their

requests, but it was not implemented.

1550

In 1550 the Liberty

of Whitby Strand, except for Hackness, was granted to

the Earl of Warwick who in 1551 conveyed it to Sir John

York and his wife Anne who sold the lease to the Cholmleys.

1580

In the reign

of Elizabeth I, Whitby was a small fishing port.

At

the end of the 16th century Thomas Chaloner visited alum works in the Papal

States where he observed that the rock being processed was similar to that under his Guisborough estate. At

that time alum was important for medicinal uses, in curing leather and for

fixing dyed cloths and the Papal States and Spain maintained monopolies on its

production and sale. Chaloner secretly brought workmen to develop the industry

in Yorkshire, and alum was produced near Sandsend Ness 5 km from

Whitby in the reign of James I. Once the industry was established,

imports were banned and although the methods in its production were laborious,

England became self-sufficient. Whitby grew significantly as a port as a result of the alum trade and by importing coal from the

Durham coalfield to process it.

1635

In 1635 the owners of the liberty

governed the port and town where 24 burgesses had the privilege of buying and

selling goods brought in by sea.

1700

Shipbuilding in Whitby increased very

rapidly during the 18th century. In 1700 113 sailboats of small tonnage were

constructed. By 1734, 130 ships of 80 tonnes and upwards were built and by

1776: 251 ships of 80 tonnes and upwards.

It was the coastal trade

which absorbed the majority of these ships and in

particular, the coal trade. Coal was shipped at Newcastle, Sunderland and

Shields for London and the east coast ports, the main part being for the

Capital. It was imported into Whitby both the domestic use and in the alum

works. In 1690, 60 tons of kelp were shipped from Berwick on Tweed to Whitby

for use in the manufacture of alum and presumably this was not an isolated

instance as the alum trade persisted throughout the century in various states

of economic decline and recovering.

1701 to 1713

The War of Spanish succession.

1731

In 1731 Whitby imported coals from Newcastle and Sunderland and wine, linen, nails, firkin staves, bricks, clog wheels (cart wheels of thick plank without spokes), and timber from Hull. There were also three cargoes of miscellaneous goods from London. 27 shipments left the port that year, one of alum for Newcastle, one of alum for Alloa and 25 for London which consisted of alum, dried fish and butter. (Willan).

1739

The War of Jenkins Ear

1740 to 1748

The War with Austrian succession

1750

Whitby about 1750

1751 to 1757

War in India.

1753

Whale fishing began in Whitby in 1753 and the vessels were sometimes used in the coal trade during the autumn and winter months and then adapted for whaling in the summer. In 1753 the first whaling ship set sail to Greenland and by 1795 Whitby had become a major whaling port.

Because of the increase in shipbuilding, large quantities of timber came into the town. Most of it was from the Baltic direct or via Hull along the coast. Whitby registered ships traded with the Baltic from Hull and London and were also engaged in the trade in the West Indies, Mediterranean, America and the East Indies. So Whitby seamen employed on locally owned ships would have picked them up at ports around the country.

There are vague hints that certain

Whitby merchants were involved with the slave trade but no definite evidence

has come to light and certainly nothing to connect the port with slave ships.

Luxury goods such as wine, tea, coffee, sugar, spices,

currents, raisins, fine dress materials and tobacco would come along the coast

from London or Hull.

One final use to which would be ships were put is that of

transport vessels in time of war. The Navy board commandeered the privately

owned vessels and paid well for their use, granting adequate recompense in the

event of loss. The crew would not fare so well if they were all pressed into

the Royal Navy.

1756 to 1763

Seven years’ war with France.

1776 to 1783

American War of Independence.

1764

Whitby benefited from

trade between the Newcastle coalfield and London, both by shipbuilding and

supplying transport. In his youth the explorer James Cook learned his

trade on colliers, shipping coal from the port. HMS Endeavour,

the ship commanded by Cook on his voyage to Australia and New Zealand, was

built in Whitby in 1764 by Tomas Fishburn as a coal carrier named Earl of

Pembroke. She was bought by the Royal Navy 1768, refitted and renamed.

1790

Whitby grew

in size and wealth, extending its activities to

include shipbuilding using local oak timber. In

1790–91 Whitby built 11,754 tons of shipping, making it the third largest

shipbuilder in England, after London and Newcastle. Taxes on imports

entering the port raised money to improve and extend the town's twin piers,

improving the harbour and permitting further increases in trade.

Whitby developed as

a spa town in Georgian times when

three chalybeate springs were in demand for their medicinal and tonic

qualities. Visitors were attracted to the town leading to the building of

"lodging-houses" and hotels particularly on the West Cliff.

Young gives the imports for 1790 as timber, hemp, flax, ashes (for soap), and iron. He makes no mention of coal that must have featured high on the list. Exports were sailcloth (7,300 bolts), butter (1,309 firkins), hams and bacons (21 tonnes 19cwts 3 qts 10 lbs), oats (4,094 qts) ad leather (33,615 lbs). Alum and whale oil, blubber, whale fins and whale bone also formed part of the export trade.

1793 to 1815

Napoleonic Wars

1814

Whitby’s most successful

whaling year was 1814 when eight ships caught 172 whales, and the whaler,

the Resolution's catch produced 230 tons of oil. The carcases yielded

42 tons of whale bone used for 'stays' which were used in the

corsetry trade until changes in fashion made them

redundant. Blubber was boiled to produce oil for use in lamps in four

oil houses on the harbourside. Oil was used for street lighting until the

spread of gas lighting reduced demand and the Whitby Whale Oil and Gas Company

changed into the Whitby Coal and Gas Company. As the market for whale products

fell, catches became too small to be economic and by 1831 only one whaling

ship, the Phoenix, remained.

1837

Burgage tenure continued

until 1837, when by an Act of Parliament, government of the town was entrusted

to a board of Improvement Commissioners, elected by the ratepayers.

The 1837 Poo Law valuation of Whitby was

a list of every property in the township of Whitby in Yorkshire in the year

1837, that is 2,435 houses, tenements, shops, offices and other places. The

valuation included the occupier of the property, its owner, a description and

its rateable value.

In 1834, the New Poor Law came into

operation in England and Wales. As part of this, parishes were grouped into

Poor Law Unions. These were administered locally by a Board of Guardians,

elected by each parish or township, and answerable to a central Poor Law

Commission, based in London. Those families who could not fend for

themselves were either given money or food to sustain themselves (known as

out-relief) or were taken into a Union Workhouse, where the workhouse master

and his staff would take care of their immediate needs. However, the workhouse

was segregated by sex and the inmates were expected to perform laborious tasks

in return for their food and lodging, so this was an option that the poor

avoided whenever possible. The funds to pay for the relief of the poor were

collected from the population of the township or parish, according to the value

of the property they occupied. The value of each property, or more

particularly, the rent it would fetch if rented for a year, was assessed. The

local Board of Guardians would decide how much they needed in each year and

each householder was liable for a proportion of this, depending on the annual

rateable value of his property.

In 1837, the Board of Guardians for the Whitby Union came to the conclusion that the rateable values that they

had been using prior to that date was out of date. They requested permission

from the Poor Law Commission to conduct a new valuation. When this was granted,

in order to record the annual rateable value of each

property, the Board of Guardians appointed a valuer. He wrote a list of

properties with their owners, occupiers and their rateable values, presumably

by walking around the town and interviewing people. This list was published by

a local printer so that people could check that their rateable value was

correct and also that no-one else was being charged

too low a rate. A copy of the list was sent to the Poor Law Commission

and it is that copy that I have transcribed.

A transcription has been made by me in the National Archives

at Kew. The original record is at the National Archives at Kew, in reference

MH12/14656. This is a large volume, ordered approximately in date order. It

contains the correspondence sent to the Poor Law Commissioners regarding the

Whitby Union and copies of their responses, from 1834 to 1843. The valuation is

towards the end of the 1837 section. More information relating to the

National Archives and how to view the documents they hold can be found on their

website

1839

In 1839, the Whitby

and Pickering Railway connecting Whitby to Pickering and

eventually to York was built, and played a

part in the town's development as a tourism destination.

George Hudson, who

promoted the link to York, was responsible for the development of the Royal

Crescent which was partly completed. For 12 years from 1847, Robert

Stephenson, son of George Stephenson, engineer to the Whitby and Pickering

Railway, was the Conservative MP for the town promoted by Hudson as a

fellow protectionist.

1857

1861

Whitby town from Abbey

Terrace, sketched on 3 October 1861

1871

The advent of iron ships

in the late 19th century and the development of port facilities on

the River Tees led to the decline of smaller Yorkshire harbours.

The Monks-haven launched in 1871 was the last wooden ship built Whitby and a year later the harbour was silted

up.

From the mid 19th century all of Whitby 's major traditional

industries, wailing, alum, shipbuilding and fishing, faced the growing

challenge of changing markets add new technological innovation. It was a town

in relative decline.

The

black mineraloid jet, the compressed remains of ancestors of

the monkey-puzzle tree, is found in the cliffs and on the moors and has

been used since the Bronze Age to make beads. The Romans are known to

have mined it in the area. In Victorian times jet was brought to Whitby by

pack pony to be made into decorative items. It was at the peak of its

popularity in the mid-19th century when it was favoured for mourning

jewellery by Queen Victoria after the death of Prince Albert.

1880s

Whitby became a town of

two halves.

There was the impressive

grandeur of the West side of the river Esk which

housed the professional classes and accommodated a growing tourist industry.

In contrast, the east side

of the river was a place of gross inequality of income and wealth. It was in

large part a ghetto of small houses, stacked together lining narrow streets and

yards clinging to the east side cliffs. It provided accommodation for the poor

of Whitby, the destitute, the unemployed, the unskilled and skilled artisans,

who provided the labour for the towns remaining shipbuilding and fishing

industries and serviced the growing needs of the west side residents.

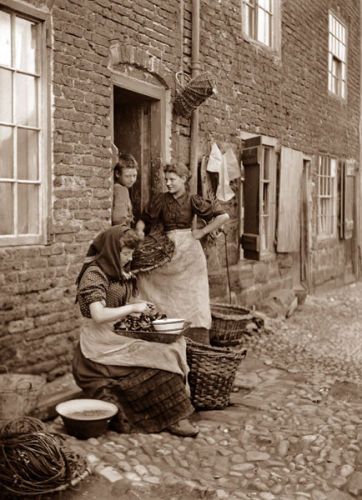

Flowergate, late nineteenth century

1891

In 1891 the census records

showed an average age of Whitby's population of 13,414 to be just 27 years old.

There were extremely high levels of infant mortality among those who lived on

the east side of the town.

1914

On 30 October 1914, the

hospital ship Rohilla was sunk, hitting the

rocks within sight of shore just off Whitby at Saltwick

Bay. Of the 229 people on board, 85 lost their lives in the disaster; most are

buried in the churchyard at Whitby.

In a raid on

Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in December 1914, the town was shelled

by the German battlecruisers Von der Tann and Derfflinger. In the final assault on the Yorkshire coast

the ships aimed their guns at the signal post on the end of the headland.

Whitby Abbey sustained considerable damage in the attack which lasted ten

minutes. The German squadron responsible for the strike escaped despite

attempts made by the Royal Navy.

1919

The Whitby Gazette of 31 January 1919 published a

letter objecting to dark, damp and crowded housing on the east side, declaring

them to be far worse than the London slums in the East End and advocating that:

“The unhealthy houses be pulled down, the streets widened, and that Whitby

shall be made into a place of health and beauty... then will be the time for

artists to paint Whitby with its red tiled roofs that are water tight.”

1955

During the early

20th century the fishing fleet kept the harbour

busy and few cargo boats used the port. It was revitalised as

a result of a strike at Hull docks in 1955 when six ships were

diverted and unloaded their cargoes on the fish quay.

1964

Endeavour Wharf, near the

railway station, was opened in 1964 by the local council.

1971

The number of vessels

using the port in 1972 was 291, increased from 64 in 1964. Timber, paper and

chemicals are imported while exports include steel, furnace-bricks and

doors. The port is owned and managed by Scarborough Borough Council since

the Harbour Commissioners relinquished responsibility in 1905.

Whitby today

Bram

Stoker arrived at Mrs Veazey’s guesthouse at 6 Royal Crescent, Whitby, at the

end of July 1890. As the business manager

of actor Henry Irving, Stoker had just completed a gruelling theatrical tour of

Scotland. It was Irving who recommended Whitby, where he’d once run a circus,

as a place to stay. Stoker, having written two novels with characters and

settings drawn from his native Ireland, was working on a new story, set in

Styria in Austria, with a central character called Count Wampyr.

Stoker

had a week on his own to explore before being joined by his wife and baby son.

Mrs Veazey liked to clean his room each morning, so he’d stroll from the

genteel heights of Royal Crescent down into the town. On the way, he took in

the kind of views that had been exciting writers, artists and Romantic-minded

visitors for the past century.

The

favoured Gothic literature of the period was set in foreign lands full of eerie

castles, convents and caves. Whitby’s windswept headland, the dramatic abbey

ruins, a church surrounded by swooping bats, and a long association with jet, a

semi-precious stone used in mourning jewellery, gave a homegrown taste of such

thrilling horrors.

Bram Stoker

photographed in about 1906

High

above Whitby, and dominating the whole town, stands Whitby Abbey,

the ruin of a once-great Benedictine monastery, founded in the 11th century.

The medieval abbey stands on the site of a much earlier monastery, founded in

657 by an Anglian princess, Hild, who became its first abbess. In

Dracula, Stoker has Mina Murray, whose experiences form the thread of the

novel, record in her diary: Right over the town is the ruin of Whitby Abbey,

which was sacked by the Danes … It is a most noble ruin, of immense size, and

full of beautiful and romantic bits; there is a legend that a white lady is

seen in one of the windows.

Below

the abbey stands the ancient parish church of St Mary, perched on East Cliff,

which is reached by a climb of 199 steps. Stoker would have seen how time and

the weather had gnawed at the graves, some of them teetering precariously on

the eroding cliff edge. Some headstones stood over empty graves, marking

seafaring occupants whose bodies had been lost on distant voyages. He noted

down inscriptions and names for later use, including ‘Swales’, the name he used

for Dracula’s first victim in Whitby.

On

8 August 1890, Stoker walked down to what

was known as the Coffee House End of the Quay and entered the public library.

It was there that he found a book published in 1820, recording the experiences

of a British consul in Bucharest, William Wilkinson, in the principalities of

Wallachia and Moldavia (now in Romania). Wilkinson’s history mentioned a

15th-century prince called Vlad Tepes who was said to have impaled his enemies

on wooden stakes. He was known as Dracula. the ‘son of the dragon’. The author

had added in a footnote: Dracula in the Wallachian language means Devil. The

Wallachians at that time … used to give this as a surname to any person who

rendered himself conspicuous either by courage, cruel actions, or cunning.

While

staying in Whitby, Stoker would have heard of the shipwreck five years earlier

of a Russian vessel called the Dmitry, from Narva. This ran aground on

Tate Hill Sands below East Cliff, carrying a cargo of silver sand. With a

slightly rearranged name, this became the Demeter from Varna that carries

Dracula to Whitby with a cargo of silver sand and boxes of earth.

So,

although Stoker was to spend six more years on his novel before it was

published, researching the landscapes and customs of Transylvania, the name of

his villain and some of the novel’s most dramatic scenes were inspired by his

holiday in Whitby. The innocent tourists, the picturesque harbour, the abbey

ruins, the windswept churchyard and the salty tales he heard from Whitby

seafarers all became ingredients in the novel.

In

1897 Dracula was published. It

had an unpromising start as a play called The Undead, in which

Stoker hoped Henry Irving would take the lead role. But after a test

performance, Irving said he never wanted to see it again. For the character of

Dracula, Stoker retained Irving’s aristocratic bearing and histrionic acting

style, but he redrafted the play as a novel told in the form of letters,

diaries, newspaper cuttings and entries in the ship’s log of the Demeter.

The

log charts the gradual disappearance of the entire crew during the journey to

Whitby, until only the captain is left, tied to the wheel, as the ship runs

aground below East Cliff on 8 August, the date that marked Stoker’s discovery

of the name ‘Dracula’ in Whitby library. A ‘large dog’ bounds from the wreck

and runs up the 199 steps to the church, and from this moment, things begin to

go horribly wrong. Dracula has arrived.

Links, texts and books

Finch,

Roger Coals from Newcastle Terence Dalton, Lavenham, Suffolk 1973.

Trevelyan,

GM A short history of England Penguin, 1942.

Willan,

T. S. The English coasting trade 1600 - 1750 Manchester University 1938.

Young,

George History of Whitby, two volumes Clark and Medd, Whitby 1817.