|

|

Farndales and Mining

On this page we explore the many Farndales who mined, mainly for ironstone, in Cleveland

|

|

Hyperlinks

to other pages are in dark

blue.

Headlines

are in brown.

References

and citations are in turquoise.

Context

and local history are in purple.

This

webpage is divided into the following sections:

·

Farndales

and Mining

·

The

Kilton Mines

·

Ironstone

mining at Great Ayton

·

Mining

in Cleveland

·

Mining

Life

·

Alum

Mining

·

Jet

Mining

·

Whinstone

quarrying

The Farndales and Mining

William Farndale was a mine labourer in

the Loftus area and an ironstone miner (FAR00260).

Thomas Farndale was a miner in Bishop Auckland (FAR00280). William Farndale was a jet miner at Eston (FAR00283).

John H Farndale was a miner of West Hartlepool who was killed aged 37 by a fall

of iron stone at the Poston Mines, Ormsby, Middlesbrough (FAR00302). John

Farndale was an ironstone miner in Ormesby (FAR00328). George

Farndale was an ironstone miner of Loftus (FAR00350C).

Martin Farndale of Tidkinhow was a miner for a time (FAR00364). John

Farndale was a miner of Egton (FAR00387).

The Kilton Mines

Further research to follow.

The

Kilton Mines

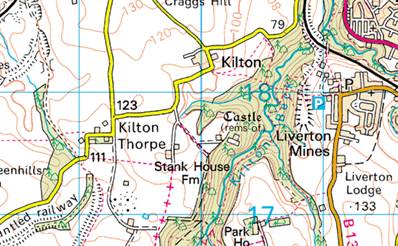

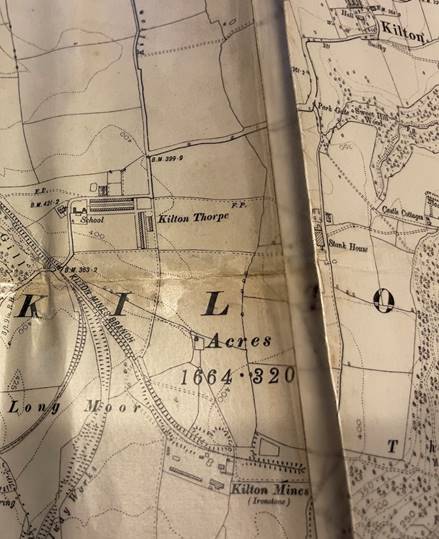

The Kilton

mines were sited to the south of Kilton Thorpe and were opened in 1871. A large

spoil tip continues to dominate the skyline. Both Kilton and Lumpsey mines were served by railways and the abandoned

embankments and cuttings of the railways are still visible. The mines finally

closed in 1963.

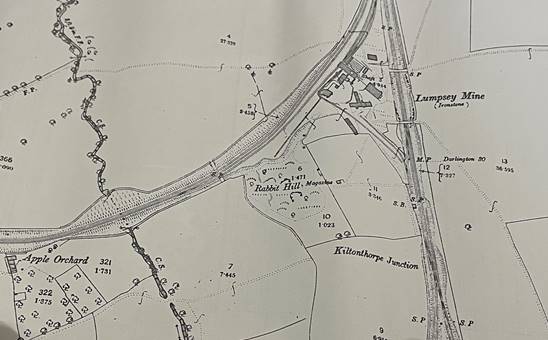

Kilton Mines, south of Kilton Thorpe in 1893

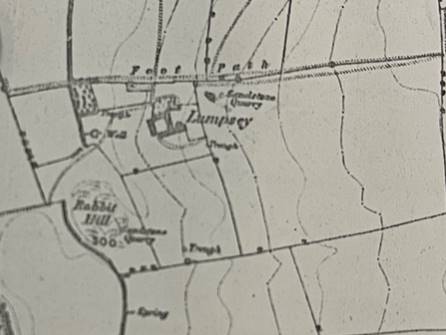

Lumpsey

The establishment of an ironstone mine in

this area in the late nineteenth century led to the destruction of the farm and

no buildings survive. The Lumpsey mine was opened in

1881, after the shafts were first sunk in 1880. The ironstone companies had

followed the veins south and east from the Eston hills. The mine occupied the

former site of Lumpsey farm and consequently no

traces were left of the farm. The mine closed in 1954 but a number of the mine

buildings still survive.

Lumpsey, 1853

Lumpsey Mines by 1893

Lumpsey Mines in 1913

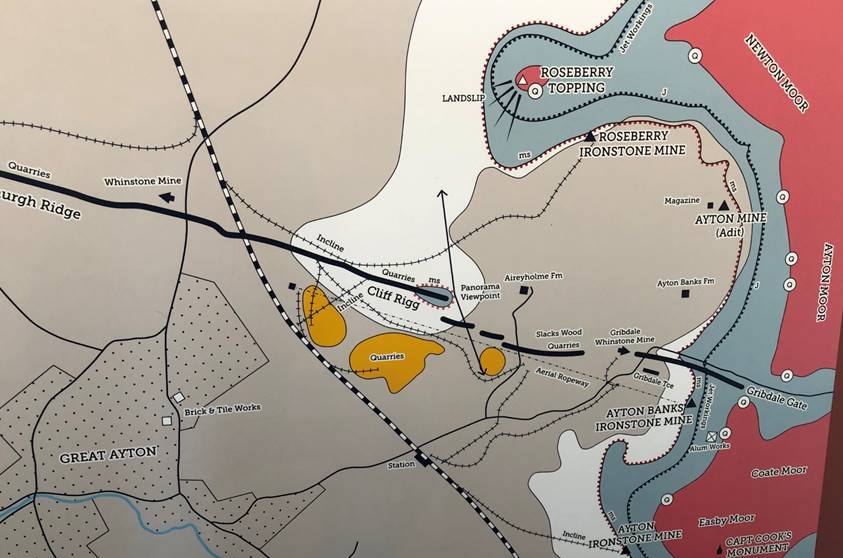

Ironstone mining at Great Ayton

There were three

ironestone mines around Great Ayton by the time of World War 1. Griddale or

Ayton Banks was a small concession operated from 1910 to 1921 by Tees Furnace

Company (OS Grid NZ 586110). The mine worked the Peckten seam of ironstone was

named after the type of fossil found in the ore. The site was not accessible

even for a narrow guage railway, so an overhead cable way was constructed,

carried on metal pillars supported by concrete bases, some of which can still

be seen.

The ironstone was mined

by drifts (“adits”) in Ayton, almost exclusively from the main seam, which was

the last of the beds to be laid down. Three mines operated in the first thirty

years of the twentieth century – Rosebury, Ayton Banks and Ayton (Monument)

Mine. They used the pillar and board method of working. The Ayton mine workings

were extensive, sgtretching as far as a second entrance north of Ayton Banks

Farm. The ore from Roseberry and Ayton mines was taken by tramway to the main

railway line. Ayton Banks ironstone was sent by aerial ropeway to the railhead.

The mines at Great Ayton

Mining in Cleveland

Ironstone comprises iron-bearing

minerals in which other elements, such as silicon, are in chemical combination.

The iron content is generally low at about 30%. Two major minerals are siderite

(iron carbonate) and bethierine (iron silicate). The

minerals were formed biochemically on the sea floor from iron either dissolved

or suspended in seawater, which was in turn derived from a nearby shore.

The economic value of ironstone depended

on (1) the iron content; (2) the thickness of the seam; (3) the presence of

shale within the seam; and (4) the content of deleterous

elements, particularly sulphur.

Between 206 and 150 Million Years, in

the Jurassic era, the rocks forming the Cleveland Hills were deposited in a

warm, shallow sea, which was later the site of a river delta. Over geological

time, these sediments were compacted to form mudstones, shales, siltstones and

sandstones. Of importance to us is the Cleveland Ironstone Formation, in the

Lower Jurassic, which is around 29 metres of shales with silty shales and with

hard beds of sideritic and chamositic ironstone.

There are five main iron-rich horizons, or seams, as follows from the lowest

upward: Avicula, Raisdale,

Two Foot, Pecten and Main Seam. Higher parts of the Jurassic sequence include

the Jet Formation, Alum Shales and sometimes coal seams, all of which had an

economic value.

The Cleveland Orefield extends over

1,000 square kilometres. The most important Main Seam was up to 5 meres in

thickness at Eston and then thinned southwards. The Loftus Mine is less then 3

metres. The shale line where shale first appears extends across the Loftus

lease, so that as mining proceeded it became necessary to separate this out as

waste. The typical iron content of Loftus was about 28%, which was distinctly

less than the Eston mines.

Iron Age

The iron stone industry began in the

Iron Age and continued to the present. There are examples of ancient stone

quarries and those at Malton and Pickering were larger mines continued from

Roman times.

Norman Mining

The Rievaulx

quarries were supported by the diversion of the water course to help with the

movement of the stone to the monastery.

Industrial Revolution

The Tees Valley was the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution and the

British Empire. At its peak, eighty three ironstone mines dispatched iron

worldwide, to make railways and bridges across Europe, America, Africa, India

and Australia (including the Sydney Harbour Bridge).

The Cleveland Ironstone Mining Museum is

situated on the site of Loftus Mine, the first mine to be opened in Cleveland.

Ironstone had long been exploited in the

area. There are, for example, extensive heaps of slag around Rievaulx Abbey,

which was supressed in December 1538. The abbey and its ironworks were acquired

by the earl of Rutland who continued working the ironworks. By 1545, four

furnaces were smelting iron ore under the management of John Blackett, the

vicar of Scawton. The vaulted undercroft

of the refectory was used to store the charcoal used as fuel. A blast furnace

was added in 1577 and a forge was re-equipped between 1600 and 1612. Local

supplies of timber for charcoal were all but exhausted by the 1640s, however,

and the ironworks closed. Other remains from this period are found in Bilsdale, Bransdale, Rosedale and near Furnace House in Fryup Dale. Many of these early working appear to have

concentrated on the Dogger Seam.

There were various attempts to mine

ironstone in the early nineteenth century, with ore being quarried on the

coastal outcrops. The Pecten seam was discovered at Grosmont

during the making of a cutting for the Whitby and Pickering Railway and the

newly formed Whitby Stone Company sent a cargo of ironstone to the Birtley Iron

Company in 1836. It was rejected as being of poor quality, and it took the

company some time to get its product right. Nevertheless, the following year

the two companies agreed a sales contract.

The Mining

and Collieries Act 1842 prohibited all underground work for women and

girls, and for boys under 10.

On 7 August 1848, the first mine in

Cleveland opened in Skinningrove.

It was not until August 1850 that Bolckow & Vaughan made a trial of the Main Seam by

quarrying near Eston. Soon the workings moved underground, using pillar and

stall, and became very large scale with over half a million tons of ironstone

was raised annually in the mid 1850s.

John Farndale wrote in 1870: Long

live Messrs Bolcklow & Vaughan, the first high spirited

gentlemen, and others also, who by their skill and capital are bringing out

resources of this greatly favoured district, and thus giving employment to

thousands.

Bolckow, Vaughan & Co Limited

was an English ironmaking and mining company founded in 1864 with capital of

£2.5M, making it the largest company ever formed up to that time.

It was founded as a

partnership in 1840 by Henry Bolckow and John

Vaughan. In 1846, Bolckow and Vaughan built their

first blast furnaces at Witton Park, founding the Witton Park Ironworks. The

works used coal from Witton Park Colliery to make coke, and ironstone from

Whitby on the coast. The pig iron produced at Witton was transported to Middlesbrough

for further forging or casting. In 1850, Vaughan and his mining geologist, John

Marley discovered iron ore, conveniently situated near Eston in the Cleveland Hills.

Unknown to anyone at the time, this vein was part of the Cleveland Ironstone

Formation, which was already being mined in Grosmont

by Losh, Wilson and Bell. To make use of the ore being mined at Eston, in 1851 Bolckow and Vaughan built a blast furnace at nearby South

Bank, Middlesbrough, to make use of the ore from nearby Eston, enabling the

entire process from rock to finished products to be carried out in one place.

It was the first to be built on Teesside, on what was later nicknamed "the

Steel River".

Middlesbrough grew from 40

inhabitants in 1829 to 7,600 in 1851, 19,000 in 1861 and 40,000 in 1871,

fuelled by the iron industry. The firm drove the dramatic growth of

Middlesbrough and the production of coal and iron in the north-east of England

in the nineteenth century.

By 1864, the assets of the

business included iron mines, collieries, and limestone quarries in Cleveland,

County Durham and Weardale and had iron and steel works extending over 700

acres (280 ha) along the banks of the River Tees.

Vaughan died in 1868. The

Institution of Civil Engineers, in their obituary, commented on the

relationship between Vaughan and Bolckow: "There

was indeed something remarkable in the thorough division of labour in the

management of the affairs of the firm. While possessing the most unbounded

confidence in each other, the two partners never interfered in the slightest

degree with each other's work. Mr. Bolckow had the

entire management of the financial department, while Mr. Vaughan as worthily

controlled the practical work of the establishment."

Chris Scott Wilson has

written more about Bolckow, Vaughan & Co.

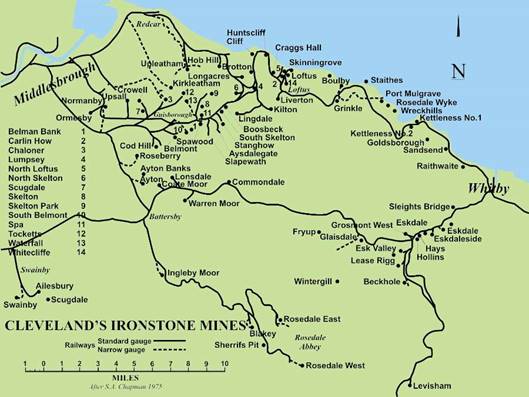

Around 35 mines opened between Eston,

Great Ayton and Hinderwell on the coast. There was a small group of mines at Grosmont and others in Rosedale. Railways were extended to

the mines, and settlements built for the labour sucked into what had been a

very rural area. After the initial rush of companies opening mines, a period of

consolidation was needed as iron companies absorbed smaller ventures and

workings were rationalised. Marginal mines closed. This process was helped by a

down-turn in trade in the early to mid 1870s. Soon, a

new generation of iron works was being built on Teesside. These used Bessemer

convertors to turn the iron into steel, which was increasingly in demand. By

1883, therefore, production of Cleveland iron ore peaked at six and

three-quarter million tons.

The quarter century before World War I

saw many older mines close, further consolidation of companies and some new

sinkings. Rock drills and mechanised haulages were used to increase efficiency

and trim costs. Around twenty mines closed in the inter-war years. Many of the

old companies were absorbed by Dorman, Long & Co. Ltd, which dominated the

industry at the start of World War II. Only nine mines, all in the area between

Guisborough and Brotton, survived the war. Efforts were made to make mining more

efficient, diesel haulage was introduced below ground, as were compressed air

loading shovels. The mines could not, however, compete with imported ore or

that worked by opencast around Scunthorpe and Corby. North Skelton Mine was the

last to close in January 1964.

Cleveland Ironstone Mines:

Mine Location Opened Closed Comments

Ailesbury Mine Whorlton 1872 1887

Aysdalegate Mine Lockwood 1863 1880 Closed

23/10/1880.

Ayton Banks

Mine Great

Ayton 1910 1929 Abandoned

July 1929.

Ayton Mine Great Ayton 1908 1930

Bagnall and Co

Mines Eskdaleside

cum Ugglebarnby 1862 1864

Beckhole Mine Egton 1857 1864

Belmont Mine Guisborough 1854 1928 Abandoned

11/11/1886. Reopened in 1907. Abandoned 20/02/1933.

Birds Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglebarnby 1858 1866

Birtley Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglebarnby 1858 1878

Blakey Mine Farndale

East 1873 1881

Boosbeck Mine Skelton 1872 1901

Boulby Mine Easington 1903 1934 Abandoned

July 1934. Boulby Potash Mine sunk here in the late

1960s.

Brotton Mine Brotton 1865 1921

California Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglebarnby 1863 1881

Carlin How Mine Kilton 1873 1924 Part

of Lumpsey until 1946.

Chaloner Mine Guisborough 1872 1939 Part

of Eston.

Cliff Mine Brotton 1866 1881 Abandoned

October 1887.

Coate Moor Mine Kildale 1866 1876 Abandoned

19/07/1876.

Cod Hill Mine Guisborough 1853 1865

Commondale Mine Commondale 1863 1876

Craggs Hall

Mine Brotton 1871 1893

Easington Mine Saltburn 1877 See

also: Port Mulgrave

East Rosedale

Mine Rosedale

East Side 1866 1926

Esk Valley Mine Egton 1859 1883

Eskdale Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglesbarnby 1906 1908

Eskdale Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglesbarnby 1856 1870

Eskdaleside

Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglesbarnby 1871 1876

Eston Mine

Guisborough 1856 1950

Farndale Mine Farndale

East 1872 1897 See

Blakey.

Fryup Mine Danby 1863 1874

Farndale Mine Farndale

East 1872 1897 See

Blakey.

Fryup Mine Danby 1863 1874

Glaisdale Mine Glaisdale 1879 Abandoned

30/03/1875.

Goldsborough

Mine Lythe 1912 1915

Grinkle Mine

Hinderwell 1872 1934 Abandoned

1934.

Grosmont Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglesbarnby 1858 1892 West

Side – Abandoned 15/05/1886.

Hays Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglesbarnby 1836 1866

Hinderwell Mine Hinderwell 1854 1862

Hob Hill Mine Marske 1864 1874 Abandoned

17/04/1875.

Hollin Hill

Mine Lockwood 1864 1880

Hollins Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglebarnby 1863 1879

Hollins Mine Rosedale

West Side 1856 1879

Huntcliffe Mine Brotton 1872 1905 Abandoned

1906.

Hutton Mine Hutton

Lowcross 1854 1867

Ingelby Mine Ingleby

Greenhow 1858 1865

Kildale Mine Kildale 1866 1878

Kilton Mine

Kilton 1871 1963 Sinking

in 1871. Closed 31/12/1963.

Kirkleatham

Mine Tocketts 1873 1885 Abandoned

31/12/1886.

Lane Head Mine Rosedale

West Side 1876 1881

Lease Rigg Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglesbarnby 1837 1850

Leven Vale Mine Kildale 1864 1871 See

Warren Moor.

Levisham Mine Levisham 1863 1874

Lingdale Mine Moorsholm 1877 1962

Liverton Mine Loftus 1866 1921 Abandoned

1923.

Loftus Mine Loftus 1848 1958 Abandoned

1959.

Longacres Mine Skelton 1873 1954 Closed

17/07/1915 and reopened from 1933 until 27/11/1954.

Lonsdale Mine Kildale 1865 1874

Lumpsey Mine Brotton 1880 1954 Sinking

in 1880. Closed 27/11/1954.

Margrave Park

Mine Skelton 1863 1874

Mirkside Mine Eskdaleside

cum Ugglebarnby 1856 1861

New Bank Mine Guisborough 1850 1950

Normanby Mine Normanby 1856 1898 Abandoned

in 1899.

North Loftus

Mine Brotton 1872 1905

North Skelton

Mine

North Skelton 1865 1964 Closed

17/01/1964.

Port Mulgrave

Mine

Hinderwell 1856 1893

Postgate Mine Glaisdale 1870 1876

Raithwaite Mine Newholm-cum-Dunsley 1854 1858

Roseberry Mine Great

Ayton 1880 1924

Rosedale East Rosedale

Abbey 1866 1925 Abandoned

1928.

Rosedale on

Coast Mine Hinderwell 1854 1876

Rosedale West Rosedale

West Side 1860 1911 Abandoned

March 1911.

Sheriffs Mine

Rosedale West

Side 1874 1911

Skelton Mine Skelton 1860 1938 Abandoned

November 1938.

Skelton Park

Mine Skelton 1868 1938 Abandoned

April 1938.

Slapewath Mine Lockwood 1864 1899

Sleights Bridge

Mine Sleights

Bridge 1856 1859

South Belmont

Mine Guisborough 1863 1875

South Skelton

Mine Stanghow 1870 1954

Spa Mine Stanghow 1864 1904 Standing

in 1903. Abandoned in 1904.

Spawood Mine Guisborough 1865 1930 Closed

28/06/1930. Abandoned April 1934.

Staithes Mine Hinderwell 1838 1860

Stanghow Mine Boosbeck 1872 1926

Swainby Mine Whorlton 1856 1868

Tocketts Mine Tocketts 1874 1877 Abandoned

in 1880.

Upleatham Mine Marske 1851 1923

Upsall Mine Upsall 1866 1927 Merged

with Eston from 1870.

Warren Moor

Mine Kildale 1864 1874

Waterfall Mine Tocketts 1892 1901

Wayworth Mine Commondale 1866 1867 Sinking

1866 to 1867.

West Rosedale

Mine Rosedale

West Side 1856 1911

Whitecliffe Mine Loftus 1871 1884

Wintergill Mine Egton 1871 1883

Wreckhills Mine Hinderwell 1856 1864

Mining Life

More work to follow

Alum Mining

John Farndale, ‘Old Farndale of Kilton’

(FAR00143) was

an alum house merchant. As John Farndale (FAR00217) wrote: ‘My

Grandfather, who was a Kiltonian, employed many men

at his alum house, and many a merry tale have I heard him tell of smugglers and

their daring adventures and hair breadth escapes.’

There is a separate page about alum mining.

Jet Mining

Another extractive industry was jet

mining. William Farndale (FAR00283) was a

jet miner at Eston.

Jet mines although numerous were small

and individual mines and tended not to acquire names or documentary records.

During the nineteenth century hard jet fetched a good price and it was mined

extensively in East Cleveland and along the edge of the moors between Roseberry

and Kildale. The mines typically took the form of parallel drifts into the side

of hills, with headings also driven at right angles to the original drifts at

regular intervals, so that the plan of the mine looked like a chequerboard, with

square pillars of rock left in place as support.

The semi precious

mineral is found in thin lenses in the jet rock generally at some depth below

the alum shales. It was extracted in Victorian times from numerous small drifts

driven into the hillside. There are spoil heaps at Gribdale

Gate and evidence of some open cast mining.

Whinstone quarrying

When the local quarrying of whinstone

first started is not known but it was well under way by the late eighteenth

century. Running through Cleveland, roughly east to west, there is a ridge

which marks the line of igneous dyke. This is composed of very hard rock called

dolerite or whinstone. This stone has been extensively mined and quarried since

the mid eighteenth century. The production of cuboid setts occupied many men

and boys. These, with their regular shapes, can still be seen around Ayton for

instance./ Most of the whinstone was taken out of the area by rail and much of

it was used for road surfacing in places such as Leeds.

Extraction had ceased by the 1960s. See for instance Cliff Rigg Mines.