|

|

A Brief History of Time in the Ancestral lands around

Farndale A

journey back through time in the period before clear records of individual

Farndales |

|

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Royal dynasties are in blue

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Local history of Farndale and its surrounding areas is in purple.

Geographical context is in green.

BCE - Before the common or current era. The contemporary

equivalent of BC.

CE -

Common or current era. The contemporary equivalent of AD.

kya

– abbreviation for a thousand years

YBP – Years before present

In contrast to other pages of this website, on this page we

travel backwards through time.

Introduction

We have explored the Farndale ancestry through

the clear and direct links provided by parish records and other sources to

about 1500, and then used medieval sources to find direct links to Doncaster at the time of the Black Death in

the fourteenth century. The medieval records have then provided some significant records of the

lives of our ancestors back to

about 1230. We have then explored

the cradle of the Farndale family, and the people who lived there, back to

the Norman Conquest.

We might imagine that those ancestral

individuals who must have lived in the dale of Farndale in the thirteenth

century, before leaving the dale but retaining its name, were in turn plucked

from the cauldron or primeval sludge of Bronze Age Beaker Folk, Iron Age

Settlers, Brigantes, Romans, Danes, Angles and Saxons that had roamed the moors

and dales of Yorkshire since about 9,000 years BCE.

So where did those more distant medieval

ancestors, who lived in Farndale, themselves come from? This page travels

backward in time from the Norman Conquest in 1066 to consider the evidence of

who our most distant ancestors may have been, roaming the area of the North

York Moors.

This webpage will work backwards through

the epochs of time as follows:

·

The early middle

ages (866 CE to 1066). Saxon

and Norman England. Anglo Saxon England was arguably united as the Kingdom

of England by King

Æthelstan (927–939 AD), although the process was a long one.

It later became part of the short-lived North Sea Empire of Cnut

the Great, a personal union between England, Denmark and Norway in

the 11th century. During this period the majority of

the Yorkshire population was engaged in small scale farming. A growing number

of families were living on the margin of subsistence and some of these families

turned to crafts and trade or industrial occupations. In the 9th Century, the

Vikings settled in many places all around the North Yorkshire Moors, but there

is no sign of them settling in the moors.

·

The post Roman period (410

CE to 866 CE). The

first written law codes, histories and literature emerged.

·

The Roman Period (70 CE to

410 CE). When

the Romans arrived in the area, they found organised resistance and strong

tribes prepared to fight for their land. The Romans came into the area further

east to patrol the coast. They built roads, part of which still exist and

warning stations on the cliffs at places like Huntcliffe. It is possible

that Roman patrols passed into the dales and even through Farndale,

but there is no evidence that they stopped there. A large fortification in

the location of modern day York was founded by the

Romans as Eboracum in 71 CE. The Emperors Hadrian, Septimius Severus, and

Constantius I all held court in York during their various campaigns. During his stay 207–211 CE, the Emperor

Severus proclaimed York capital of the province of Britannia Inferior, and it

is likely that it was he who granted York the privileges of a 'colonia' or

city.

·

The Iron Age (700 BCE to

70 CE). Iron

tools and weapons changed the fighting and working world, though dwellings and

lifestyles did not change significantly. Communities and tribes, although

warlike became more settled and cereal production and animal husbandry

increased. Iron Age farmsteads were made up of groups of small square or

rectangular fields and were often enclosed by low walls of gravel or stones.

Their huts were made of branches, or wattle and stood on low foundations of

stone. There was a massive hill fort at Roulston Scar, which dates

back to around 400 BC. It is the largest Iron Age fort of its kind in

the north of England. There are outlines of other such settlements near

Grassington and Malham. The most impressive Iron Age remains are at Stanwick,

north of Richmond.

·

The Bronze Age (1800 BCE

to 700 BCE). The

Bronze Age was the period when metal ore was discovered. Copper was alloyed

with tin. By applying very high heat levels to ceramic crucibles it was

possible to alloy bronze and to caste axe heads, knives, spear heads, and

simple ornaments. This was the period represented by the Windy Pit discoveries,

including Beaker People pottery and human remains. The use of bronze was

probably introduced into Yorkshire by the Beaker Folk, who entered the area via

the Humber Estuary in about 1800 BCE.

·

The Neolithic Period, the New

Stone Age (3000 BCE to 1800 BCE). The New Stone Age was the period when tool making

skills produced stone axes, flint axes, arrow heads, spear points, fired clay

beakers and woven cloth. Neolithic society made pottery, weaved cloth and made

baskets. These people no longer lived a semi nomadic existence. Permanent

settlements were built, like to one at Ulrome, between Hornsea and Bridlington,

where a dwelling built on wooden piles on the shore of a shallow lake has been

found.

·

The Mesolithic Period

(9,500 to 3,000 BCE). The

Middle Stone Age was the period after the ice had receded. Microlith sites have

been found on the Moors including at Farndale,

including flint and stone chippings and tools. Early humans lived at Star Carr

which was first occupied in about 9,000 BCE.

·

The

last Ice Age dated from about 110,000 to 11,000 years ago. During that Ice Age

there were warm and cold fluctuations which lasted long enough to explain the

presence of sub tropical animals in Kirkdale cave.

·

The Palaeolithic Period or the Old Stone Age (10,000 BCE

to 2.6 million year ago). The Palaeolithic Period,

also known as the Old Stone Age, is a period in human prehistory

distinguished by the original development of stone tools. This period

covers about 99% of human technological prehistory. It extends

from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominids in Africa

about 3.3 million years ago, to the end of the Pleistocene.

Although this period covers human prehistory on a global scale, humans do not

appear to have emerged on the North Yorkshire Moors until about 9,000 BC,

during the Mesolithic Period.

The early middle ages (1066 back to 866 CE)

The period from the Danish colonisation

of 866 AD to the

Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 was strongly influenced by Danish

colonisation, especially in the area of the Deiran and Bernician lands that

would merge into Northumbria. Viking

meant pirate or sea raider, but the English generally referred to them as

Danes.

1066

Edward the Confessor died in January

1066.

Tostig’s brother, Harold II (Harold Godwineson) (1066 to 1066) was elected king by the Witan, but

William I of Normandy claimed that Edward had promised the throne to him. In

the context of a power struggle, Harold was then faced with a combined threat

from a reinvasion by the Danes and from the Normans.

Tostig had fled to Flanders and had

gathered a fleet of 60 ships. He entered Lincolnshire but was driven out and

fled to Scotland with only 12 ships. Harld Hardrada, King of Norway accepted

the exiled Tostig as allies and they sailed up the Humber and Ouse with 300

ships.

The Danes, led by the

Norwegian King Harold Hardrada, sailed up the Ouse, with support from Tostig

Godwinson and after the Battle of Fulford, they seized York. Harold then

marched his army north to York (185 miles) in four days and took the invaders

by surprise. They were defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge (some 10km

east of York) in which Harold Hardrada and Tostig were killed.

There is an In

Our Time podcast on the

Battle of Stamford Bridge, the decisive English victory over Viking forces

which took place in September 1066.

However Harold was then required to rush south

again, with so much of his exhausted army as could keep up, to face William I

at the Battle of Hastings.

1063

Earl Tostig had the supporters of his

rival, Gospatrick of Bamburgh – Gamal son of Orm, and Ulf son of Dolfin, killed in

York in 1063.

Tostig then sought to increase taxation

which prompted opposition. The Northumberland folk revolted in 1065 and marched

on York and Tostig’s Danish housecarfs (a force of about 200) were destroyed

near the Humber. Tostig was outlawed.

1055

The beautiful Saxon Church

of Kirkdale lies about a mile west of

Kirkbymoorside, south of the North York Moors, and overlooks the Hodge Beck.

Within the porch at the entrance door is housed a Yorkshire treasure. It is a

Saxon sundial, and it bears the inscription “Orm the son of Gamel acquired

St Gregory’s Church when it was completely ruined and collapsed, and he had it

built anew from the ground to Christ and to St Gregory in the days of King

Edward and in the days of Earl Tostig”. The inscription refers to Edward

the Confessor and to Tostig, the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and brother of

Harold II, the last Anglo Saxon King of England. Tostig was the Earl of

Northumbria between 1055 and 1065. It was therefore during that last peaceful

decade, immediately before the Norman conquest, that Orm, son of Gamel rebuilt

St Gregory’s Church.

The Domesday book

evidences that Kirkdale by about this time comprised ten villagers, one priest,

two ploughlands, two lord’s plough teams, three men’s plough teams, a mill and

a church. Orm

seems to have held five carucates of land at Chirchebi. So presumably this area

of land described the five carucates of cultivated land around Kirkdale.

Siward

died in 1055, leaving one son, Waltheof. He was buried at St Olave’s Church,

which he had built, just north of York’s walled boundary.

Siward’s son, Waltheof was too young to

become Earl of Northumbria. King Edward chose Tostig, son of Earl Godwin of

Wessex to succeed Siward.

1053

Harold Godwineson became earl of Wessex.

The Godwines by now were largely running the country.

By this time York had seven

administrative districts, with one controlled by the Archbishop.

The townsmen had extensive pasture rights in the surrounding area. Archaeology

has revealed significant manufacturing in metal, glass, amber, jet, deer horn,

wood and bone.

Local

organisation focused around a lord’s great hall (later

called manors by the Normans). From these would satellite outlying demesne

farms which were called berewicks. Free men held soke estates.

There were some larger sokes which belonged to the King, church or Earl.

In other words, there was an informal hierarchy from larger to smaller

lordships. (John Rushton, The History of Ryedale,

2003, 23).

Over seventy thegns are listed in the

Domesday Book, including the large landowner Ormr, who held Kirkbymoorside,

Earl Siward, Gamal, Tosti and Ughtred of Cleveland.

Arable farming focused around vills or towns.

Tax was assessed on cultivated land

through caracutes (derived from the Latin carruca, plough) and bovates.

Early assessments were therefore focused on the amount of ploughing that could

be achieved in an area of land. These initial measures would last through time,

even though methods of ploughing changed. A carucate was a medieval land unit

based on the land which eight oxen could till in a year.

The dales flowing down from the moorland

remained thinly settled.

It is not clear how strongly held

Christian belief were at a local level. Many pagan customs continue. The days

Tuesday through to Friday are still named after Anglian and Norse Gods. Hills

remained dedicated to the Norse Gods Odin and Woden, Much Yorkshire folklore

remains rooted in Anglian and Norse traditions. Hobs and boggles remained in field

names. However masonry at churches evidences Christian

assimilation. The settlement at Chirchebi that would be the burgeoning

lands of Kirkbymoorside was a small rural community focused around

the church of St Gregory and its priest. The eleventh century sundial at

Kirkdale is the best preserved of several including others at Edstone and Old

Byland.

1051

The rivalry between the Godwine family

and the Normans started to bubble over. There was a violent dispute in Dover

between Normans and the locals. The Godwines were ordered by the King to punish

the Dover folk, but they refused. They were outlawed and exiled, but they were

sufficiently powerful that Edward was persuaded to reconciliation.

1050

According to William, Duke of Normandy, Edward

named William as Edward’s successor to the English crown.

There was a succession battle waiting to

happen:

·

Cnut’s

heirs were waiting in the wings.

·

The

Godwine family, vast landowners and now married in to

the royal family, were staking their claim.

·

William

of Normandy had also staked his claim.

1044

Edward the Confessor married Edith,

daughter of Earl Godwine. They had no children.

1042

Edward

“the Confessor” (1042 to 1066) restored the

House of Wessex to the English throne. He became king in 1042 as Aethelred’s

surviving son, Cnut’s sons having died early. He is remembered for his deep

piety which led to his focus on the building of Westminster Abbey while the

country was generally run by Earl Godwin and Harold.

By this time many of the names of towns

and places were of Viking origin, such as those ending in by or thorp.

However the old Anglo Saxon names

remained abundant suggesting an assimilation during the Viking times rather

than a period of ethnic cleansing. Scandinavian language

survived widely in the countryside.

1040

Harthacanute

(1040 to 1042)

was the son of Cnut and

Emma of Normandy was quickly accepted as king as he sailed to England with a

fleet of 62 ships. He died at the age of 24 at a wedding when toasting the

health of the bride. He was the last Danish King of England.

1035

Harold

I (Harold Harefoot) (1035 to 1040) was Cnut’s

‘illegitimate’ son claimed the throne while his brother Harthacanute was in Scandinavia, but died before Harthacanute needed to invade

to retake the throne.

1033

Cnut chose a

fellow Dane, Siward, as his Yorkshire Earl.

1030

The Horn of

Ulph is an eleventh-century oliphant (a horn carved from an elephant's

tusk). It is two feet four inches long, and has a

diameter at the mouth of five inches. Given its size and condition, it is a

particularly good example of a medieval oliphant. Tradition holds that it is a

horn of tenure, presented to York Minster by a Norse nobleman named Ulph

sometime around 1030. This suggests that a powerful Scandinavian nobleman was

willing to donate a very valuable object to the Christian church by this time.

1016

Edmund

II “Ironside” (1016 to 1016),

was chosen by the folk of London as Aethelred’s successor but the King’s

Council, the Witan, chose Cnut. Ironside denoted Edmunds

strength and endurance in battle, but Edmund was defeated at the Battle of

Assandun and made a treaty with Cnut for a form of power sharing until he was

assassinated.

Cnut

(or Canute) “the Dane” (1016 to 1035) then became

king of a united England, divided into four earldoms of East Anglia, Mercia,

Northumbria and Wessex. Siward of Northumbria appeared in Shakespeare’s

Macbeth. Leofric, Earl of Mercia was married to Lady Godiva who rode naked

through Coventry to persuade him not to impose a tax increase. There is an In Our Time podcast on Cnut.

In an attempt to reassure the indigenous population, he

married the widow of Aethelred II, Emma of Normandy and he recognised the

limitations of his powers in the famous scene when he ordered the tide not to

come in, in the knowledge that he would not succeed.

About 130 years into the birth of the

English nation, she had become a part of the North Sea empire.

1013

By 1013 he had fled to Normandy after

the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard had invaded the burgeoning English lands from

1013 on the pretext of a massacre of Danes living in England on St Brice’s Day.

Sweyn had come up the Humber that year.

Sweyn was pronounced King of England on 25 December 1013, but died 5 days later. Aethelred returned to England but spent his

remaining years at war with Sweyn’s son, Cnut.

1000

By about 1000, the lands were commonly

referred to as Engalond, of various spellings.

991 CE

The renewal of Danish attacks on

southern England from 975 CE led to the payment of a regular tribute, the

Danegeld from 991 CE.

Aethelred made a fateful treaty in 991

CE with Richard , Duke of Normandy. In the same year a

fleet led by King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway led to the death of his ealdorman

Byrhtnoth at Maldon in Essex. After Maldon, Aethelred raised he sums by a

universal land trax to bribe the Danes, known as the Danegeld. The weight of

taxation drove the peasantry to servitude. Rudyard

Kipling later lamented that once you have paid him the Dane geld, you

never get rid of the Dane.

There is an In

Our Time podcast on the

Danelaw.

Yorkshire had a Danish

leadership who were unwilling to fight other Danes and there was less trouble

there.

978 CE

Aethelred

II “The Unready” (978 to 1016 CE) failed in the

ongoing resistance against the Danes. He was dubbed unready from unraed

or ill advised.

Ethelread the Unready was the first Weak King of

England and was thus the cause of a fresh Wave of Danes (1066 and

all that, Walter Sellar and Robert Yeatman, 1930).

975 CE

Edward

the Martyr (975 to 978 CE) became king

at the age of 12 and was the victim of a family power struggle until his murder

by his stepmother at Corfe Castle.

959 CE

Edgar

(959 to 975 CE)

met the “six kings of

England” and gained their allegiance at Chester, including from the King of

Scots, the King of Strathclyde and various Welsh princes. Edgar imposed lighter taxation and allowed

greater autonomy across the area of modern Yorkshire, which became assimilated

into the wider English Kingdom.

York remained the only sizeable town and

became a centre for craftsmen and merchants. The town had a level of self

government under the hold or High Reeve.

The wider district started to take its

name after the town of York. The Shire started to recognise three Ridings,

which were themselves divided into some 28 wapentakes (perhaps named after the

brandishing of weapons at gatherings to show approval). Often the waopentakes

were named after their meeting places at hills, burial mounds, crosses or

trees.

The land of St Cuthbert at Durham

retained a separate identity.

For a period

there were no invasions. Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury increased the

power and the wealth of the monasteries.

By about this time:

·

Agriculture

started to prosper.

·

Law

enforcement was generally conducted at a local level. Men were divided into

tithings or groups of ten men, to look out for each other, and bonded together

through feasting and drinking together. Ten tithings would form small units to

chase rustlers and bandits.

·

A

relatively homogenous form of customary law emerged.

·

There

was an English church and English saints.

·

A

wide coinage was in circulation with the King’s head.

·

An

administrative system emerged based upon the scir or shire, governed on

behalf of the king by an ealdorman and his deputy or scirgerefa

(sheriff).

·

Significant

numbers came to be involved in the administration of the kingdom, including the

collection of tax.

·

The

people of the kingdom were given a form of representation by gatherings of

thegns and prelates who became councillors of the witan who were summoned from

time to time by the king.

·

The

export of wool became a mainstay.

·

Roads,

bridges and harbours were maintained publicly.

The new kingdom was

perhaps one of the stablest and richest lands amongst the European states. However its fragile process for the succession of kings (by

a mix of inheritance, bequest and election) was a weakness which would dominate

the following century.

955 CE

Eadwig (955 to 959 CE) was a

teenage king who was perhaps best remembered for being late for his coronation

after sleeping in.

954 CE

Then, in 954 CE, King Eric

I of Norway of the Fairhair dynasty (Eric Haraldson known as Eric Bloodaxe) was

slain at the Battle of Stainmore by King Eadred who retook the city at Jorvik

and completed the unification of England.

946 CE

Eadred (946 to 955 CE) continued

to resist the Danes.

939 CE

Edmund (939 to 946 CE) became king

at the age of 18, having fought with his half brother at the Battle of

Brunanburh. He consolidated Anglo Saxon control over northern England.

937 CE

The Norse-Gaels, Ostmen or

Gallgaidhill became Kings of Jorvik after long contests with the Danes over

controlling the Isle of Man, which prompted the Battle of Brunanburh. After his

victory against an invading army of Irish Vikings, Scots and Britons at

Brunanburh. Aethelstan was proclaimed rex Anglorum, king of the English.

In one of the bloodiest battles faught in Britain, Aethelstan defeated a

combined army of Danes and Vikings, Scots and Celts. The battle meant that for

the first time the Anglo Saxon kingdoms were brought

together to establish a unified England.

927 CE

Aethelstan

defeated the Vikings at York and

there was peace until 934 CE.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the reign of King Athelstan, whose

military exploits united much of England, Scotland and Wales under one ruler

for the first time.

The Vale

of York Hoard, also known as the Harrogate Hoard and the Vale of York

Viking Hoard, is a 10th-century Viking hoard of 617 silver coins and 65 other

items. It was found undisturbed in 2007 near Harrogate. It was deposited in

about the period 927 to 927 CE.

924 CE

Aethelstan (924 to 939 CE) extended

the boundaries of the Anglo Saxon lands.

920 CE

All the rulers in Britain

submitted to Edward the Eler as father and lord.

899 CE

Edward the Elder (899 to 924 CE) retook the south east from the Danes up to the Humber and united Mercia

with Wessex. However there were multiple Danish

invasions including from Ireland and Scandinavia. Edward was killed fighting

the Welsh at Chester.

The Swedish Munsö dynasty became overlords of Jorvik because the Danes in

Britain had promised loyalty to the Munsö Kings of Dublin, but this dynasty was

focused on the Baltic Sea economy and quarrelled with the native Danish Jelling

dynasty (which originated in the Danelaw with Guthrum).

890 CE

In the late 9th century

Jorvik was ruled by the Christian King Guthfrith. It was under the Danes that the ridings and wapentakes of Yorkshire and the Five

Burghs were established. The ridings were arranged so that their

boundaries met at Jorvik, which was the administrative and commercial centre of

the region.

886 CE

Alfred seized London and the Anglo Saxon Chronicle wrote that all the English race turned

to him. This might be taken to be the birth of the English nation, but not yet

the mark of a united English kingdom. Alfred was perhaps the first king who

might have been believed to be king of Angelcynn and defender of the eard

(the land). Yet the English were not yet a nation.

866 CE

Aethelred I (866 to 871 CE) struggled

with the Danes throughout his reign who started to threaten Wessex itself.

In 866 CE, when

Northumbria was internally divided, the Vikings captured York. The

Danes changed the Old English name for York from Eoforwic,

to Jorvik. The Vikings destroyed all the early monasteries in the area

and took the monastic estates for themselves. Some of the minster churches

survived the plundering and eventually the Danish leaders were converted to

Christianity. Jorvik became the Viking capital of its British lands and it would reach a population of 10,000. Jorvik

became an important economic and trade centre for the Danes. Saint Olave's

Church in York is a testament to the Norwegian influence in the area. Jorvik

perhaps prospered from its trade with Scandinavia.

Genetic mapping indicates

that whilst Norwegian DNA is still detectable in northern groups, especially in

Orkney, no genetic cluster in England corresponds to the areas that were under

Danish control for two centuries. The Danes were highly influential militarily,

politically and culturally but may have settled in numbers that were too modest

to have a clear genetic impact on the population.

879 CE

In 879 Alfred summoned his army to meet

at Ecgberht’s Stone and they were joined by the folk of Somerset and Wiltshire,

hey attacked the Danes at Ethandun (Edington) and defeated the Danes who agreed

to be baptised.

875 CE

In 875 CE, Guthrum became leader of the Danes and he apportioned lands to his followers. Most of the

indigenous population were allowed to retain their lands under the lordship of

their Scandinavian conquerors. Ivar the Boneless became "King of all

Scandinavians in the British Isles".

871 CE

Alfred the Great (871 to 899 CE) has been

remembered in history as educated and practical, a Christian philosopher king.

After some initial success against the Danes under Guthrum, the Danish king of

East Anglia, the Danes launched a counter attack and

Alfred famously retreated to the marshland of Athelney in the Somerset levels

to regroup. He established Christian rule over Essex and then more widely

across the Anglo Saxon Kingdoms. He founded a permanent army and a small navy.

He began the Anglo Saxon chronicles.

There is an In Our Time podcast on King Alfred and the defeat

of the Vikings at Battle of Edington and Alfred's project to create a culture

of Englishness.

865 CE

By 865 CE a great heathen

horde (a micel here) attacked in East Anglia and began to challenge the

political balance of the Anglo Saxon Kingdoms. Large mobile encampments arose

across the land, including at Aldwark near York.

858 CE

Aethelbald (858 to 860 CE) was the

second son of Aethelwulf.

Aethelbert (860 to 866 CE) witnessed

the sacking of Winchester by the Danes, although the attackers were then

defeated.

850 CE

After 850 CE, Viking raiding parties

started to camp through the winter. They started to obtain horses and became

more mobile.

839 CE

Aethelwulf

(839 to 858 CE)

was King of Wessex and

father of Alfred. He defeated a Danish army at Oakley.

By the mid ninth century there was an

increasing influence of Scandinavian culture including upon the language. Many

words of modern use in northern dialect have Norse origins, including dale

(from the the Norwegian ‘dalr’, valley), beck (stream) and fell

(mountain).

835 CE

Opportunistic raids by Viking warrior

seamen continued over the next half century. By 835 larger Viking fleets began

to engage in more significant confrontations with royal armies.

The effects of Viking raids on the

indigenous peasant population, who were exposed to violence and enslavement,

must have been profound. The impact was also political as warlords sometimes

made alliances with the Danes, or were forced to

resist them.

827 CE

Egbert

(827 to 839 CE) was the

first Saxon King to establish relatively stable rule across Anglo Saxon

England.

Wave of Egg Kings. Soon after this event,

Egg Kings were found on the thrones of all these kingdoms, such as Eggberd, Eggbreth, Eggfroth etc. None of these, however, succeeded in becoming

memorable, expect, insofar as it is difficult to forget such names as Eggbirth, Eggbred, Eggbeard, Eggfish etc. Nor is it

remembered by what kind of Eggdeath they perished (1066 and

all that, Walter Sellar and Robert Yeatman, 1930).

793 CE

The first known Viking raid on the

British Isles was the assault on Lindisfarne off the modern Northumbrian coast

in 793 CE. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle and accounts by

Alciun in the Frankish Kingdom of Charlemagne describe a violent a bloody

scene.

On 8 June 793 Vikings raided

Lindisfarne, their first attack on the British Isles. The raid was devastating

for the community of Lindisfarne, but had ominous

implications for the wider religious and political world. By 875 CE monks at

Lindisfarne decided to leave and they took St Cuthbert’s coffin with them to

Chester le Street and then to Durham.

Viking Raiders, ‘Judgement Day” Stone, c800 to 825 CE – a procession of

seven men, six armed with swords and axes.

At that time, there was no united kingdom called England. Instead

there were smaller kingdoms dominated by Wessex in the south west, Mercia in

the Midlands, East Anglia in the eastern fenlands, and Northumbria in the

north, with which we are most interested. These kingdoms had evolved out of the

chaos after the withdrawal of the Romans from Britain. They are often

collectively referred to as Anglo Saxon kingdoms.

Alcuin, the Scholar of York, wrote

of the Lindisfarne raid: … never before has

such a terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race.

Nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold, the

church of Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of

all its ornaments, a place more venerable than all in England is given as a

prey to pagan peoples.

The Anglo Saxon

Chronicle recorded This year came dreadful forewarnings over the land of the

Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully; these were immense sheets

of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying

across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great

famine; and not long after … the harrowing inroads of heathen men made

lamentable havoc in the church of God on Holy Iland, by rapine and slaughter.

The post Roman

period (866 CE back to 410 CE)

During the period 410 to

866 CE, Angle and Saxon farmers settled in the dales and small villages started

to emerge.

The town at

the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss, today known as York, had

developed from Roman Eboracum, following a period of decline, to a

settlement of the Angles by the fifth century CE. By the seventh century CE, Eoforwic

was the chief city of King Edwin of Northumbria. The first wooden monster

church was built in Eoforwic in 627 CE for Edwin’s baptism. After 633 CE

the wooden church was rebuilt in stone. In the eight century CE Alcuin of

Eoforwic was at the centre of a Cathedral school.

There is a separate page

on Alcuin

of York.

The area of Farndale has been described as and area stretching, ‘northwards

from the Wolds, of windswept moors of Hambleton and Cleveland (Cliffland) and still remain much as they were in pre-historic times. A

refuge of broken peoples, a home of lost causes.’ Bede described the area

as ‘vel bestiae commorari vel hommines bestialiter vivre conserverant.’

(A land fit only for wild beasts and men who live like wild beasts). When the

Romans left the Saxons in very small numbers did venture into the dales on the

moors and left their burial mounds and stone crosses on the high ground and

these can still be seen. Thus the people who

today come from the dales of the North Yorkshire Moors were a relatively

isolated population for several hundred years and they had developed very

special characteristics. In many respects, this has provided a uniqueness.

Diet

In Northumbria from about

500 CE, the diet of the folk who lived in Anglo Saxon Britain was likely based

on cereals, bread and porridge with vegetables including onions and leaks,. Peas and white carrots. Meat was eaten very rarely and fish was caught in rivers. Hunting was a sport of

nobles and wild boar and deer might have been taken

from time to time. Food would have been cooked at an open fire in the middle of

a dwelling in a large iron pot hung over the fire. Bread might have been baked

in clay or stone ovens outside.

731 CE

The Venerable Bede (672 or 673 to 26 May 735)

(“Saint Bede”) was an English monk and an author and

scholar who wrote the

Ecclesiastical History of the English People which he completed in

about 731 CE. He was one of the greatest teachers and writers during the Early

Middle Ages, and is sometimes called "The Father

of English History". He served at the

monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul at Monkwearmouth

and Jarrow in the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria.

The Life of

the Venerable Bede, on the state of Britain in the seventh century,

begins: In the seventh century of the Christian era, seven Saxon kingdoms

had for some time existed in Britain. Northumbria or Northumberland, the

largest of these, consisted of the two districts Deira and Bernicia, which had

recently been united by Oswald King of Bernicia ... The place of his birth is

said by Bede himself to have been in the territory afterwards belonging to the

twin monasteries of Saint Peter and Saint Paul at Weremouth and Jarrow. The

whole of this district, lying along the coast near the mouths of the rivers

Tyne and Weir, was granted to Abbot Benedict by King Egfrid two years after the

birth of the Bede.... Britain, which some writers have called another world,

because from its lying at a distance it has been overlooked by most

geographers, contained in its remotest parts a place on the borders of

Scotland, where Bede was born and educated. The whole country was formed

formerly studded with monasteries, and beautiful cities founded therein by the

Romans, but now, owing to the devastations of the Danes and Normans, has

nothing to allure the senses. Through it runs the Were, a river of no mean

width, and of tolerable rapidity. It flows into the sea and receives ships,

which are driven thither by the wind, into its tranquil bosom. A certain

Benedict built churches on its banks, and founded there two monasteries, named

after St Peter and St Paul, and united together by the same rule and bond of

brotherly love.

Bede gave intellectual and religious

significance to as burgeoning nation at Jarrow from where many centuries later John William

Farndale was the youngest member of the Jarrow marchers. Bede first defined

an English identity. Bede produced the greatest volume and quantity of writing

in the western world of his time. At his monastery at Jarrow

he had access to a university library with more books than were in the

libraries of Oxford or Cambridge 700 years later. (Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 24, 26).

685 CE

By about 685

CE, the early church at Kirkdale was dedicated

to St Gregory. There are two elegant tomb stones within its grounds which are

once said to have borne the name of King Oethelwald. More recent excavations

tend to suggest that the church at Kirkdale was important.

The origin of

parish churches emerged at about this time. A parish was a district that

supported a church by payment of tithes in return for spiritual services. Some

churches were linked to manor houses and others originated as the districts of

missioning monasteries. The church at Whitby was

near a major settlement, whilst the church of St Gregory’s at Kirkdale was

located remotely in a dale. By 1145, Kirkdale was described as the church of

Welburn. Recent excavations tend to confirm the view that an important church

was at Kirkdale (John Rushton, The

History of Ryedale, 2003, 19).

In

contrast to the trackless moorland wilderness haunted by wild beasts and

outlaws where Lastingham was built, in Kirkdale, an ancient route from north to

south descended out of Bransdale to form a crossroads with an ancient route

from west to east along the southern edge of the moors. Travellers needed

shelter, medical attention and perhaps spiritual sustenance. It may well have

been to provide these Christian ministrations and to teach the gospel in the

region that a small community of monks was established there as a minster

(Latin monasterium) dedicated to Gregory the Great, English Apostle. It

has been speculated that the original settlement in Kirkdale was an early

offshoot of Lastingham. Inside the Minster, two finely decorated stone tomb

covers, generally agreed to date from the eighth century, hint that this early

church had wealthy patrons - perhaps royal patrons at least one of whom may

have been venerated in Kirkdale as a saint.

We

don't know exactly when the first church was built at Kirkdale. It may have

been a daughter house of the monastic community at nearby Lastingham, which was

founded in AD 659. The first church at Kirkdale was a minster, or mother church

for the region. It may have included a chancel - a rarity for Anglo-Saxon

churches. Surviving from that early building are two

finely carved 8th-century stone grave covers inside the church. The quality of

the carving suggests that the church had wealthy patrons, perhaps of a locally

royal family. The Friends of

St Gregory's Minster Kirkdale suggest that at least one of these

8th-century patrons may have been venerated locally as a saint. There are also

three fragments of Anglo-Saxon cross shafts built into the church walls. These

cross shafts date to the 9th and 10th centuries.

Pope

Gregory (St Gregory) sent St Augustine on his mission to convert the English to

Christianity in AD 597 (see below). The Minster is dedicated to him.

It

seems likely that the minster fell into ruin, perhaps as a

result of Danish raids. We know that the church was rebuilt around 1055 because

of the clue in the sundial (see further above).

Pope Gregory had

encouraged the conversion of pagan holy places to Christianity and the church

at Kirkbymoorside is near a large burial mound.

670 CE

In the 670s Cuthbert, said

to have been inspired by a vision of Aidan’s death to have joined to

monasteries at Ripon and then Melrose, joined Lindisfarne as prior and became 7th

Bishop of Lindisfarne in about 685 CE. He aimed to reform the monk’s way of

life in compliance with the religious practices of Rome, rather than Ireland.

He later became a hermit on St Cuthbert’s island and

later on Inne Farne. He died on 20 March 687 and is

buried inside he church at

Lindisfarne.

Bishop Eadrith

(died in 721 CE) later commissioned Bede to write the Life of Saint Cuthbert.

In about 700 CE Eadrith also created the illuminated

manuscript Lindisfarne

Gospels, in honour of St Cuthbert. Bishop Aethelwold of Lindisfarne bound

it and Billfrith created a jewelled metalwork cover. The manuscript combined

influences from Mediterranean, Irish and Anglo Saxon

traditions.

There

was for a time some disagreement between the Roman and Lindisfarne missions.

This caused conflict within the church until the issue was resolved at the Synod of Whitby in 663 by Oswiu of Northumbria opting

to adopt the Roman system.

The

schism had come about because the church in the south were tied to Rome, but

the northern church had become increasingly influenced by the doctrines from

Iona. The Synod was held in the monastery at Streoneschalch near to Whitby.

659 CE

Christianity in Ryedale

and the stone crosses of the Ryedale School

Many local churches in

Ryedale date back to the Anglo-Saxon period. The churches are not the earliest

evidence of the arrival of Christianity to the north of England. The first

evidence was the establishment of a chain of monastic sites from Lindisfarne down

the coast to Whitby,

their influence then extending inland to Crayke, Lastingham and Hackness. The

Venerable Bede recorded that in 659 CE the monk Cedd hallowed an inauspicious

site at Lastingham and established there the religious observances of

Lindisfarne where he had been brought up. By the time Bede was writing in circa

730 CE, there was a stone church at Lastingham.

Christianity was spread through

the work of missionaries who travelled the countryside, often erecting

preaching crosses. They were originally made of wood, but with the re

introduction of building in stone, stone crosses became the norm. These

preaching crosses depicted scenes from the Bible and were often elaborately

decorated with motifs from the Mediterranean. The carvings may have originally

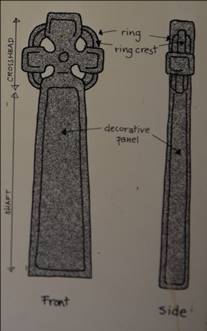

been painted in bright colours. In the central part of Ryedale there were local

Craftsman who produced such crosses which were unique in their design. A

typical Ryedale School cross was about 6 feet tall with a slightly tapering,

flat, oblong section shaft. The style occurs in Kirkbymoorside, Levisham and

Middleton. The Ryedale dragon is an ornamentation on the back panel of the

cross shaft. A single beast, often in an S shape, filled the whole panel.

There is an In

Our Time podcast on the Celts.

Bede,

in his History of the English Church and People (731

CE), records that in 659 CE, a small monastic community was planted at

Lastingham under royal patronage, partly to prepare an eventual burial place

for Æthelwald, Christian king of Deira, partly to assert the presence and

lordship of Christ in a trackless moorland wilderness haunted by wild beasts

and outlaws.

Chap.

XXIII. How Bishop Cedd, having a place for building a monastery given him by

King Ethelwald, consecrated it to the Lord with prayer and fasting; and

concerning his death. [659-664 a.d.] The same man of God, whilst he was bishop

among the East Saxons, was also wont oftentimes to visit his own province,

Northumbria, for the purpose of exhortation. Oidilwald,425 the son of King

Oswald, who reigned among the Deiri, finding him a holy, wise, and good man,

desired him to accept some land whereon to build a monastery, to which the

king himself might frequently resort, to pray to the Lord and hear the

Word, and where he might be buried when he died; for he believed

faithfully that he should receive much benefit from the daily prayers of those

who were to serve the Lord in that place. The king had before with him a

brother of the same bishop, called Caelin, a man no less devoted to God, who,

being a priest, was wont to administer to him and his house the Word and the

Sacraments of the faith; by whose means he chiefly came to know and love the

bishop. So then, complying with the king's desires, the Bishop chose himself

a place whereon to build a monastery among steep and distant mountains,

which looked more like lurking-places for robbers and dens of wild beasts,

than dwellings of men; to the end that, according to the prophecy of

Isaiah, “In the habitation of dragons, where each lay, might be grass with

reeds and rushes;”426 that is, that the fruits of good works should spring up,

where before beasts were wont to dwell, or men to live after the manner of

beasts.

650 CE

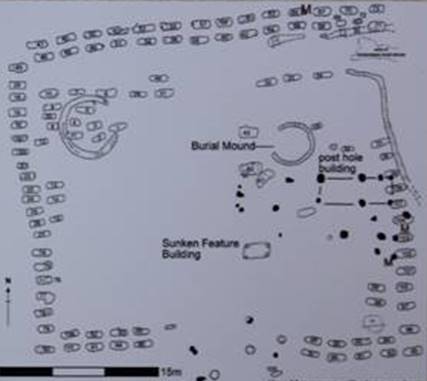

An

aristocratic burial ground at Street House near

Loftus and Carlin How, dates to about

650 CE, a period of transition from paganism to Christianity in England. The

cemetery was superimposed on a prehistoric monument and contained a high ranking woman on a bed surrounded by 109 graves,

arranged two by two. The location would have been just within the northern

border of Deira. The royal princess watched over Carlin How (“the hill

of witches”) for thirteen centuries until she was excavated in 2005 to 2007.

The cemetery was only used

for a short period of time. The cemetery is focused on one burial near the

centre of the cemetery, known as grave 42. The objects from this grave were the

first indication to archaeologists that this was an important person. The grave

contained three gold pendants, each one unique in

northern England. The female had been placed on a wooden bed with iron fittings

and decoration. Bed burials are very rare and had only been found previously in

southern England.

There are only a small

number of bed burials in England including two at the royal cemetery at Sutton

Hoo in Suffolk. The bed was placed in a chambered tomb with a low mound marking

the site of the grave. Other graves define the extent of the burial area as an

irregular square 36 metres by 34 metres. There are two buildings within the

cemetery, one possibly a mortuary house where the princess from grave 42 may

have been laid prior to her burial. The cemetery was created within an earlier

Iron Age enclosure dating to about 200 CE and the link to the past may have

been deliberate. Grave 42 is the richest single Anglo-Saxon grave in the North East defined by the quantity and quality of the

material found. The main pendant is unique in its shield like

shape. The pendant is made of gold with 57 small red gemstones sitting on a

thin gold alloy foil. The pendant may have been made from gold coins from the

continent that had been debased.

During the seventh century CE, burial

practises in England had changed. The people had converted to Christianity and

Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had emerged. The more gold or precious objects the more

important the person.

This diorama

at the Kirkleatham

Museum represents the Royal Saxon settlement

excavated at modern day Street House. It shows the unusual layout of the

cemetery, including the bed burial structure, the people and the building of

the settlement, and a small ship at the beach at nearby Skinningrove, as her

crew traded goods with the local inhabitants.

Lindisfarne became one of

the focal Christian centres in Europe between about 650 to 750 CE. It gained

power and wealth, taking grants of land from kings and noblemen, and many

precious objects.

642 CE

Oswald died after a short

reign in 642.The new king was Oswy (Oswald’s brother). He gave land on six

estates to monasteries through Deira including Streoneshalch (later Prestby)

near Whitby in 657.

634 CE

Edwin's successor, Oswald (634 to 642 CE), dominated the northern region from

his royal fortress at Bamburgh. He was sympathetic to the Celtic church and

around 634 he invited Aidan from Iona to found a

monastery at Lindisfarne as a base for converting Northumbria to Celtic

Christianity. The monastery at Lindisfarne observed Irish Christian customs.

Aidan was the first Bishop

of Lindisfarne. He was known as the ‘Apostle of Northumbria’. He died in 651

and was reportedly buried in the church at Lindisfarne.

Aidan soon established a

monastery on the cliffs above Whitby with

Hilda as abbess.

Further monastic sites were established at Hackness and Lastingham and Celtic Christianity

became more influential in Northumbria than the Roman system.

There is a traditional

story that a monastery was built at Oswaldkirk in Ryedale,

but was never finished.

633 CE

Edwin’s defeat at the

Battle of Hatfield Chase by Penda/King Caedwalla of Mercia in 633 was followed

by continuing struggles between Mercia and Northumbria for supremacy over

Deira.

The Northumbrian empire

briefly fell apart, but it was recovered by the Christian King Oswald.

627 CE

Edwin converted to the

Christian religion, along with his nobles and many of his subjects, in 627 and

was baptised at Eoforwic. Edwin built the first church at Eoforwic (York)

amidst the Roman ruins and it was later replaced by a

larger stone church.

When

Augustine came to Britian, he does not appear to have attempted to bring his

mission to Northumbria. However

Edwin, King of Northumbria, married the daughter of Ethelbert, the converted

king of Kent and it was agreed that she should freely exercise her religion.

She was accompanied by a zealous pupil of Augustine, Paulinus, and this

provided the basis for Edwin’s conversion. From that time, Paulinus was

increasingly employed in conversion across the region of Northumbria (South Yorkshire, the History and Topography of the

Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York by Rev Joseph Hunter,

1828, page xiv, Bede’s Ecclesiastical

History, Chapter 9).

Stone

crosses or spelhowes/spel crosses started to appear in the landscape,

which seem to have been meeting places of early local government. There is a story that Kirkdale church was first built on

the site of such a stone cross.

617 CE

A later ruler, Edwin of

Northumbria (son of Aelle of Northumbria)(617 to 633)

completed the conquest of the area by his conquest of the kingdom of Elmet,

including Hallamshire and Leeds, in 617 CE. He killed Æthelfrith and became

King of all Northumbria.

Edwin married Princess

Aethelburgh of Kent who brought a priest, Paulinus, from Augustine’s mission in

Canterbury and Edwin was baptised in 627 CE.

604 CE

Æthelfrith took over Deira

in about 604 CE and there was significant expansion of Anglo

Saxon power.

From about 604

CE, Æthelfrith was able to unite Deira with the northern kingdom of Bernicia,

forming the kingdom of Northumbria, whose capital was at Eoforwic,

modern day York.

By the early seventh

century, there was a diversity of language – Germanic, Brittonic, Gaelic and

Pictish and later Norse. In the north, predatory chieftains were occupied in

raiding, rustling and slaving. Rival kingdoms appeared with Northumbria emerging

as the most powerful, with its main city at York. (Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

23).

Place

names which end ingaham, ing, ham, ington, burn,

lea, feld, tun were originally Anglo Saxon homesteads.

599 CE

King Aethelric ruled Deira in about 599 to 604 CE.

597 CE

Pope Gregory sent Augustine,

prior of a Roman monastery to Kent on an ambassadorial and religious mission to

convert the Angli, and he was welcomed by King Aethelberht.

The English church would

come to own a quarter of cultivated land in England

and it brought back literacy. English identity began in a religious concept.

The country was now

almost entirely inhabited by Saxons and was therefore named England, and thus

(naturally) soon became C of E. This was a Good Thing, because previously the

Saxons had worshipped some dreadful gods of their own called Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday … (1066 and

all that, Walter Sellar and Robert Yeatman, 1930).

580 CE

The historian Procopius

(500 to 565 CE) described the people of Brittia as Angiloi to

Pope Gregory the Great, Gregory had seen fair haired slaves for sale and

replied that they were not Angles, but angels. His pun is sometimes

taken to define the origin of the English and Gregory continued to class them

as a single peoples.

Noticing some fair haired

children in the slave market one morning, Pope Gregory, the memorable Pope,

said (in Latin), “What are those?” and on being told they were Angels, made the

memorable joke (‘not Angels, but Anglicans’) and commanded one of his saints

called St Augustibne to go and convert the rest (1066 and

all that, Walter Sellar and Robert Yeatman, 1930).

Hence there grew a single

and distinct English church. It adopted Roman practices in its dogma and

liturgy (as later confirmed at the Synod of Whitby in 663 CE), but it venerated

English saints and developed its own character.

569 CE

King

Aella ruled Deira in about 569 to 599 CE. You will find a dynastic history of

the Kings of Deira.

560 CE

This

was followed by the subjugation of all of eastern Yorkshire and the British kingdom of Ebruac in about

560 CE. The name

the Angles gave to the territory was Dewyr, or Deira. Early rulers of

Deira extended the territory north to the River Wear.

There is a legendary story

that an Anglian called Soemil founded the Kingdom of Deira. There were early settlements

at Fyling south of Whitby. Early movement inland tended to branch out along the

old Roman roads.

The indigenous population

suffered from mid sixth century plague and rising water levels, so it is

possible that there was little resistance to the Angles.

Circa 500 CE

In the late fifth and

early sixth centuries Angles from the Schleswig-Holstein peninsula began

colonising the Wolds, North Sea and Humber coastal areas.

Fifth Century CE

At the end of Roman rule

in the fifth century, the north of Britain may have come under the rule of

Romano-British Coel Hen, the last of the Roman-style Duces Brittanniarum (Dukes

of the Britons). However, the Romano-British kingdom

rapidly broke up into smaller kingdoms and York became the capital of the

British kingdom of Ebrauc. Most of what became

Yorkshire fell under the rule of the kingdom of Ebrauc

but Yorkshire also included territory in the kingdoms of Elmet and an unnamed

region ruled by Dunod Fawr, which formed at around this time as did Craven.

Saxon settlements appeared across Britain, especially to the south and east,

but also in the north. The Saxons didn’t displace the indigenous population,

but there was violence evidenced by hoards of treasure buried to escape the

increasing threat.

The population of Britain

fell from a few million to fewer than one million people after the Romans left

in the fifth century. Over the next few centuries, groups of Angles and Saxons

arrived from northwest Germany and southern Denmark, taking advantage of a

‘failed state’. They established a dominant Anglo-Saxon culture which

influenced the lands that would become England.

Life was nasty, brutish

and short. This was the context of the Arthurian legends.

Genetic mapping indicates

that most of the eastern, central and southern parts of England formed a single

genetic group with between 10 and 40 per cent Anglo-Saxon ancestry. However,

people in this cluster also retained DNA from earlier settlers. The invaders

did not wipe out the existing population; instead, they seem to have integrated

with them.

Transforming events were

taking place across the world at this time – the Chinese Empire reunited under

the Tang dynasty, the Roamn empire reestablished itself at Constantinople and

Islam began its conquest of western Asia and Iberia (Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 21).

The Scots (originally

Irish but by now Scotch) were at this time inhabiting Ireland, having driven

the Irish (Picts) our of Scotland; while the Picts

(originally Scots) were now Irish (living in brackets) and vice versa. It is

essential to keep these distinctions clearly in mind (and verce

vice) (1066 and all that, Walter Sellar and Robert Yeatman, 1930).

The Roman Period

(410 CE back to 71 CE)

Yorkshire

was part of the Roman Empire between 71 CE and 410 CE. The Romans did not

advance into north eastern Yorkshire beyond the River

Don, which was the southern boundary of the Brigantian territory.

The legions were recruited

from all across the Roman Empire. However, there is

very little evidence today of a genetic legacy from other Roman dominions.

The Romans built roads

northwards to Eboracum (modern York), Derventio (Malton) and Isurium Brigantum

(Aldborough).

During the period 700 BCE

to 410 CE, the climate was cooler and wetter. Soils on the high ground of the

North Yorkshire moors had been exhausted. Farmers moved to lower ground. The

moorland generally reached about the same extent as exists today.

410 CE

There is an In Our Time podcast on the causes and events leading to the fall of the Roman Empire

in the 5th century and assesses the role of Christianity, the Ostrogoths,

the Visigoths and the Vandals.

The withdrawal of the

Roman legions … left Britain defenceless and subjected Europe to that long

succession of Waves of which History is chiefly composed (1066 and

all that, Walter Sellar and Robert Yeatman, 1930).

408 CE

Roman Britain faced

threats from north Britain and Scots in Hibernia. Saxons from northern Germans

and southern Scandinavia started to threaten the north sea

coast and the Romans stationed increasing troops along the coast and built

extensive fortifications. By the time of a significant Saxon attack in 408 CE,

Britain was becoming a drain on Roman resource who were facing simultaneous

threats across Europe.

402 CE

In 402 CE the Roman garrison at Eboracum was

recalled because of military threats from other parts of the empire. The

Roman legions started a process of withdrawal from Britain.

306 CE

Constantius I died in 306 CE during his stay in Eboracum, and his son Constantine the Great was

proclaimed Emperor by the troops based in the fortress.

296 CE

A century or so of relative

peace seems to have ended by about 296 CE and Eboracum became more of a

command post for the Dux Britanniarum, the Roman Commander of northern

Britain. The Dux Britanniarum was a military post in Roman Britain, probably

created by Emperor Diocletian or Constantine I during the late third or early

fourth century. The Dux (literally, "(military) leader" was a senior

officer in the late Roman army. His responsibilities covered the area along

Hadrian's Wall, including the surrounding areas to the Humber estuary in the

southeast of today's Yorkshire, Cumbria and Northumberland to the mountains of

the Southern Pennines. The headquarters were in the city of Eboracum

(York). The purpose of this buffer zone was to preserve the economically

important and prosperous southeast of the island from attacks by the Picts

(tribes of what are now the Scottish lowlands) and

against the Scots (Irish raiders).

There is an In Our Time podcast on the Picts.

The fortifications at

Malton were rebuilt.

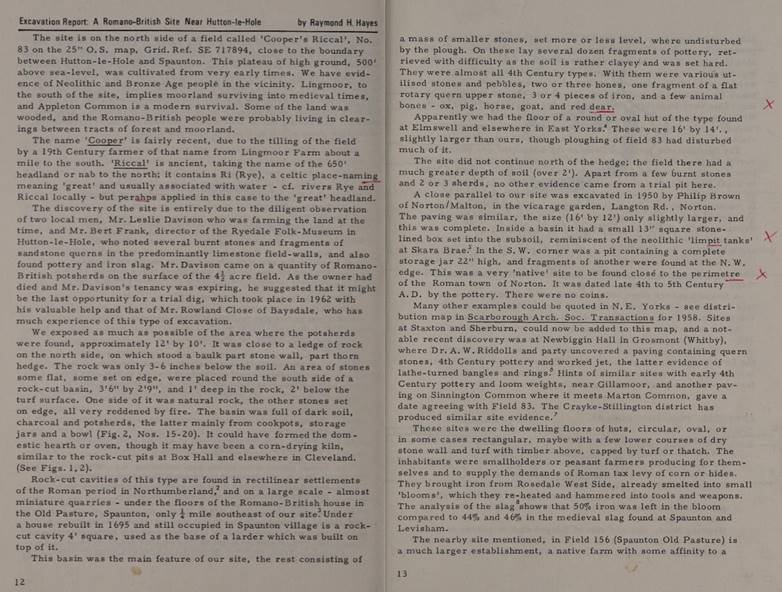

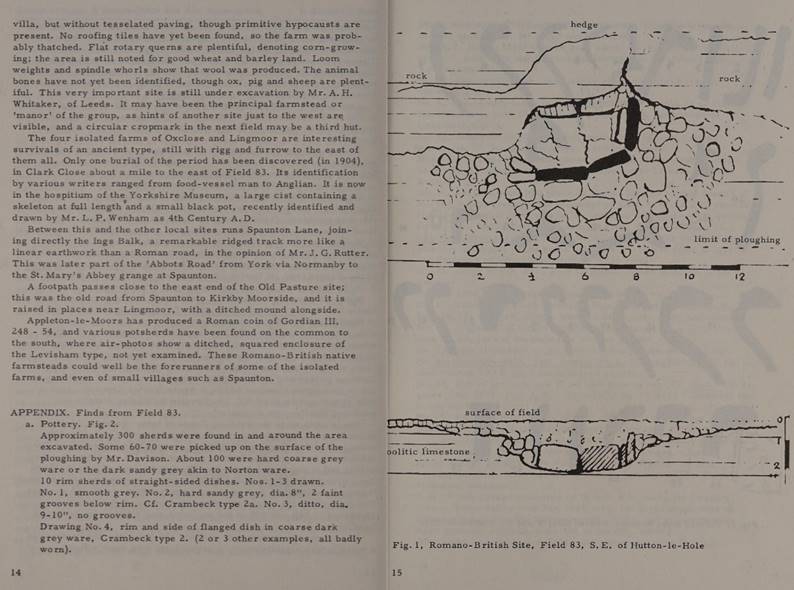

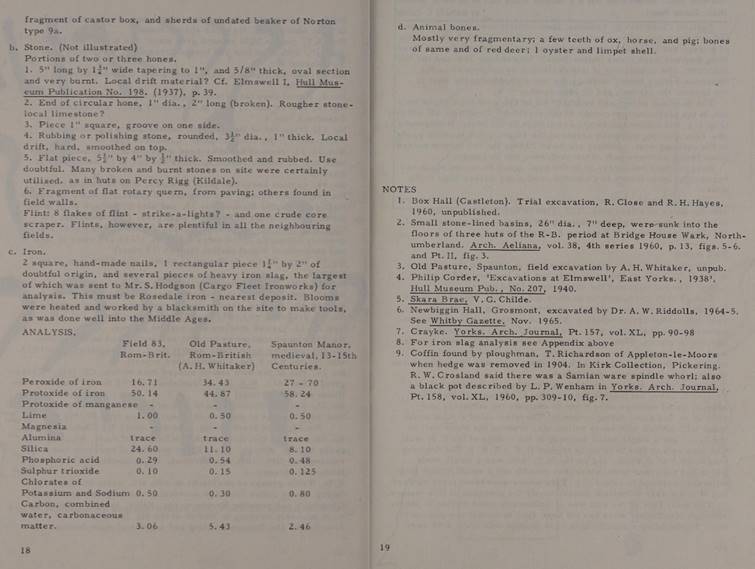

Romano British site near

Hutton le Hole (Ryedale

Historian Vol 2, 1966)

The Beadlam

Villa (Ryedale Historian Vol 3, 1967)

Excavations Roman

Villa at Beadlam, 1996.

207 CE

During his stay 207–211

CE, the Emperor Severus proclaimed Eboracum capital of the province of Britannia

Inferior, and it is likely that it was he who granted York the privileges of a

'colonia' or city.

122 CE

The Emperor Hadrianus

sealed off the far north by a military zone focused on Hadrian’s Wall which was

built between 122 to 138 CE and was one of the most significant engineering

projects of the ancient worlds.

During the Roman period,

Most of Britannia remained rural: 80 per cent of the population lived in over

100,000 small settlements and some 2,000 villas (Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 12).

77 CE

In 77 CE Agricola became

governor and extended Roman domination northwards.

The rulers organised

agriculture and economic activity, some based on slave labour, around villas in

the countryside. They expanded towns and built roads to speed the progress of

their legions between military forts. Yet in the more remote areas of western

and northern Britain, life continued much as before.

The Romans came into the

area further east to patrol the coast. They built roads, part of which still

exist and warning stations on the cliffs at places like Huntcliffe. It is

possible that Roman patrols may have passed through the heavily forested dales

flowing from the high moors, including Farndale, but there is no

evidence that they stopped there, and it seems more likely that they would have

ignored the impenetrable woodland areas.

There is an In Our Time podcast on Roman Britain.

A

significant military camp was founded by the Romans as Eboracum (modern day York) in 71 CE.

Urban settlements grew around the Roman fortifications at York (Eboracum),

Malton and Stamford. Eboracum became a significant Roman provincial capital.

To the south Roman urban settlements grew around fortifications

at Calcaria (Tadcaster) and Danum (Doncaster).

The Roman legions brought

with them craftsmen who made nails, shoes and pottery, or maintained iron edged

tools, lead piping and the like. The towns around the military zones developed

their own craftsmen and patterns of trade. The Roman army needed food, clothes,

horses, drink and the like. The towns developed forms of amusement and

relaxation and amenity and administration.

Evidence of imported goods

from the Roman period have been found, Bronze statues of

Venus and Hercules have been found around Malton. Pieces of toilet seats have

been found in Gillamoor.

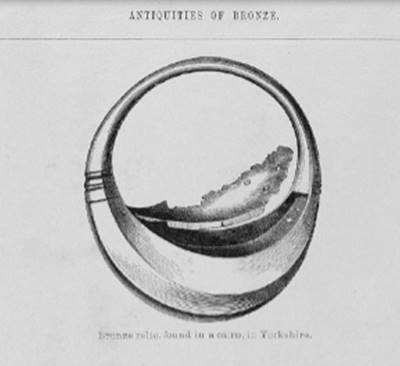

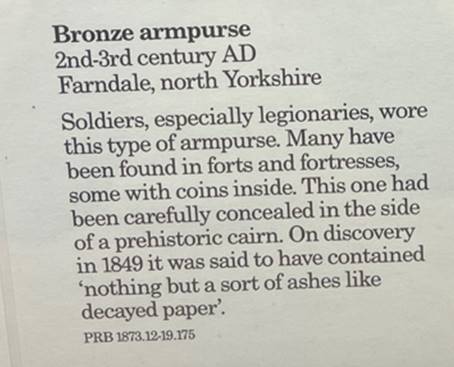

There has been a find of a bronze arm-purse on a high moor track

above Farndale in 1849.

Roman copper-alloy arm-purses appear to have been principally, if not

exclusively, a male, military accoutrement, with examples found both in

auxiliary and legionary contexts in Britain and on the Continent. British

examples include finds from Birdoswald (x2), Corbridge, South Shields,

Thorngrafton (near Housesteads), Colchester, Wroxeter, Silchester and Farndale.

The

find is from a track above Farndale, so may not evidence Roman

activity within the dale, but it does suggest some influence, perhaps

patrolling, in the immediate vicinity.

At the time

of writing, the purse can be seen in the British Museum (Museum Reference

Number 1873,1219.175), on display in Room 49, case 9. This gallery is located

on the upper floor of the museum.

43 CE

From the year 43 CE, Roman

influence had transformed the way of life of people in southern and eastern

Britain. The emperor Claudius commanded a force of some 40,000 men, with

elephants to boot. They were grouped into four legions supported by auxiliaries.

Over the following decades

the Romans came to dominate Britain. Resistance by Caratacus was quickly

subdued and the druids were massacred on Anglesey in 60 CE. He then faced

revolt to the east from the Iceni and their king’s widow, Boadicea.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the Druids.

There

is an In Our Time podcast on Boudica.

55 and 54 BCE

Prior to the Roman period

in Britain, Julius Caesar, having expanded northwards and fighting his wars in

Gaul, was drawn to an early invasion when Britons allied with the Gauls. He

landed in Kent with a force about 30,000 strong and advanced to the Thames.

Though he met a disunited resistance, he withdrew quickly to deal with the

ongoing threat to the Roman army in Gaul.

The Iron Age (70 CE

back to 700 BCE)

The

Bronze Age people, such as the Beaker Folk were conquered by Celtic speaking

invaders from the Mediterranean and later focused in

northern Gaul. They settled in Britain and became known as the Brigantes, who have colloquially been referred to

as Ancient Britons. The Celts were skilled horsemen. They went into battle with

iron wheeled, horse drawn chariots, and attacked their enemy with swords and

spears.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the dawn of the European Iron Age, a period of

great upheaval when technology and societies were changed forever.

The Brigantes were not the only Celtic tribe to

occupy northeast Yorkshire. In Holderness and the Wolds area, were a folk known

as the Parisii (who came from France and Belgium).

The

Brigantes were a highly organised society, with a hierarchy of military rulers.

The mobility provided from their horsemanship enables them to control lager

areas.

Their

farmsteads were made up of groups of small square or rectangular fields and

were often enclosed by low walls of gravel or stones. Their huts were made of

branches, or wattle and stood on low foundations of stone.

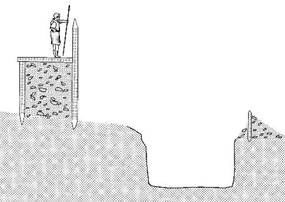

There was a massive hill fort at Roulston Scar, which dates back to around 400 CE. The site covers 60 acres, defended by a perimeter 1.3 miles

long. It is the largest Iron Age fort of its kind in the north of England.

There are

outlines of other such settlements near Grassington and Malham. The most

impressive Iron Age remains are at Stanwick, north of Richmond.

The Brigantes fought hard to defend themselves against the Roman invaders.

Several large fortifications witness their efforts. The last inhabitants of the

area before the Romans were illiterate, but left their

mark in the place names of Yorkshire. Many

Yorkshire rivers carry Celtic names - Aire, Calder, Don, Nidd, Wharfe.

The Brigantes were a

Celtic tribe who lived between the Tyne and the Humber.

The Brigantes and Parisii

were led by a tribal leader, sometimes elected, and sometimes from a leading

aristocratic family such as Boudicca who later fought the Roman army. They

lived in large settlements, sometimes on hilltops and sometimes in the lowlands.

There is such a site at Stanwick near Darlington where pottery has found

covering a large area which had come from the continent. The main Parisii

settlement was probably close to Brough near Hull. There is evidence that the

aristocracy lived in rectangular enclosures often about 60 by 80 metres with two metre wide defensive ditches piled high inside for

further protection. The homes, similar to Iron Age

roundhouses, may have been established in groups of two or three. Each

enclosure farm worked about 250 acres and the fields around the farms grew

cereals and hay for winter feed. The non aristocratic folk would have worked

the land in the enclosure farms for their masters.

The Brigantes and Parisii

have left evidence across modern Ryedale of round houses within enclosed sites.

Roulston Scar at Sutton Bank is a limestone

cliff which overlooks the Vale of York, between Helmsley and Thirsk (some 20km

to the west of Kirkbymoorside and Farndale). It is a large Iron Age promontory

fort dating to about 500 to 400 BCE.

Iron furnace remains and

slag from smelting have been found. Iron ore may have been mined in Rosedale.

Those living closer to the sea may have picked up or from the beaches. The

Bronze Age is the period when for the first time the land had been cleared for

growing crops and rearing cattle and sheep. Significant advancement was made in

culture and politics and the use of land. The landscape may have looked similar to the present day but with more woodland in the

valleys and no towns or roads. There may have been tracks for wheeled vehicles.

Costa Beck is a small river in Ryedale, North Yorkshire. Excavations from

ther 1920s have revealed Iron Age lakeside settlements through the Vale of Pickering.

Animal bones, pottery sherds and a human skull have been excavated.

There are

several sites in the Pickering Vale, including at Heslerton where there were

small enclosures for stock breeding and growing crops in the wetlands around

the once Lake Pickering.

In 320 BCE, the Greek

explorer, Pytheas sailed around Britain and called it Pretannike,

probably from the Celtic for ‘tatooed’, from which evolved Britannia

over time. The larger island of the British Isles came to be called Alba

or Albion and the western island (modern Irland) Ivernia or Hibernia.

Centuries later in the History of the Kings of

Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth,

in 1136, a story emerged that the Trojan Brutus had landed in Albion finding

only giants and named the land Brutaigne.

The Bronze Age (700

BCE back to 1,800 BCE)

The use of

bronze was probably introduced into Yorkshire by the Beaker Folk, who arrived in the area via the Humber

Estuary in about 1800 BCE.

Beaker folk

They came across the Wolds and crossed

the Pennines. Their name is derived from their tradition to bury beaker shaped

urns with their dead.

Beaker Folk reached Malham Moor and occupied sites on the Wolds. There is

evidence that they cultivated wheat and there is evidence of trade. They

imported flat bronze axes from Ireland. They exported ornaments made of Whitby jet. They traded in salt and had sea

connections with Scandinavia.

Possibly transition into the Bronze Age

came about by invasion, or it may have evolved through trade and peaceful

contacts.

The people of the Bronze Age continued

to hunt in upland areas. There have been finds of their barbed and tanged flint

arrowheads. Gradually these were replaced with metal tools and weapons. There

is evidence during the Bronze Age of metal working and tin mining, leather and

cloth manufacturer, pottery and salt production. There was domestic trade and

trade beyond the island’s shores.

The population steadily grew to perhaps

about 2 million.

The Bronze age was a time of changes in

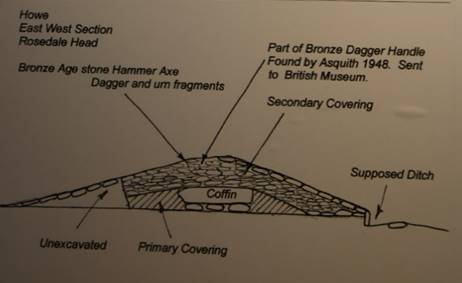

burial rituals. Bodies were buried beneath circular mounds (round barrows)

often accompanied by bronze artefacts. There are

many barrows in upland locations on the Wolds and the Moors.

Early Bronze Age burials were performed

at Ferrybridge Henge.

There is a Street

House Long Barrow (later added to by an Anglo Saxon

royal burial site) at Loftus, where many

later Farndales lived and are buried.

Round barrows of the early

part of the Bronze Age are the most conspicuous archaeological features of the

North York Moors. The

scarcity on lower ground is due mainly to agricultural activity. Those on

higher ground have generally been found to contain cremations, while those on

lower ground in limestone areas contained both burnt and unburnt bodies. The

skeletons are most often accompanied by pottery (beakers, food vessels,

collared urns and accessory cups), and flints, and sometimes by jet ornaments,

stone battle axes and occasionally by bronze daggers. Collared urns and

cremations have also been found with stone embanked circles such as at Great Ayton moor.

Yorkshire

Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 22 January 1936: In Cleveland, and especially on the eastern moorlands,

remains are few and far between. Yet Guisborough has produced a bronze helmet,

and Farndale moor a bronze arm purse, probably loot; while on the coast from

Saltburn to Filey stand the foundations of five watchtowers erected at the time

of Saxon peril.

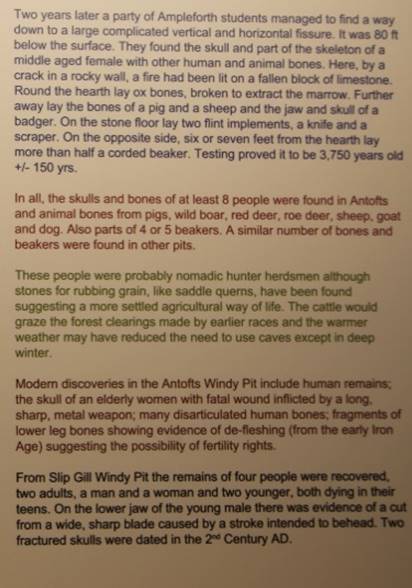

The Ryedale

Windy Pits are archaeologically significant natural underground features

within the North York Moors National Park. This series of fissures in

the Hambleton hills, near Helmsley, is located on the western slope above the

river Rye. Warm or cold air rises from the fissures and comes

into contact with the air outside the entrance. In winter a steamy

vapour rises in puffs or jets from the holes. There are over 40 known windy

pits, but only four windy pits have known significant archaeological deposits.

These are Antofts, Ashberry, Bucklands and Slip Gill. The windy pits have

strange vertical shafts with occasional horizontal chambers rising within the

limestone cliffs. They are accessed from the surface through small openings in

the woodland floor. The near vertical shafts are sometimes 70 feet deep. In all

the skulls and bones of at least eight people were found in Antofts and animal

bones from pigs, wild boar, red deer, roe deer, sheep, goat and dog as well as

four or five beakers have also been found. The human remains include the skull

of an elderly woman with a fatal wound inflicted by a long sharp, metal weapon

and many disarticulated human bones.

Bronze age

hoards of axes cast in bronze have been found at Keldholme and Gillamoor. There

are barrows and tumuli such as at Whinny Hill Farm near Kirkbymoorside and

Keldholme and a road in the centre of Kirkbymoorside, Howe End, circles the

site of a howe, a large round mound which contained several burial sites.

Ryedale

Historian Vol 9, 1978:

There is an In Our Time podcast on the Bronze Age collapse,

sudden, chaotic change around 1200 BC, mainly in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Neolithic

Period, the New Stone Age (3,000 BCE to 1,800 BCE)

The New Stone Age was the

period when tool making skills produced stone axes, flint axes, arrow heads,

spear points, fired clay beakers and woven cloth.

A revolutionary advance

was made in the cultural development of northeast Yorkshire at around 3000 BCE.

This was the arrival from continental Europe of the first Neolithic (New Stone

Age) settlers. These people must have crossed in boats; probably in dug out

canoes. The Neolithic Revolution involved arable farming and the domestication

of animals.

Neolithic society made pottery, weaved cloth and

made baskets. These people no longer lived a semi nomadic existence. Permanent

settlements were built, like to one at Ulrome,

between Hornsea and Bridlington, where a dwelling built on wooden piles

on the shore of a shallow lake has been found.

Ulrome

The Neolithic people buried their dead with ceremony, in chambered mounds called barrows. There are examples of long and round barrows.

The

start of stone age farming in

the area of the north Yorkshire moors

was in about 3,000 BCE, though there is some evidence of

farming from about 5,000 years ago. By 3,000 BCE permanent settlements were

built by Neolithic people.

From about 2,000 BC huge prehistoric

monuments appeared in the Megalithic Period. The organisation required erect the

large megalithic structures and the barrows suggests highly developed society.

The largest standing stone in Britain is

a single pillar of grindstone, 25 feet high. It dominates the churchyard at Rudstone, a few miles west of

Bridlington. The nearest source of stone is 10 miles north of the site.

Small village communities

became settled, more reliant upon domestic animals and less on hunting. They