Act 7

The Poachers of Pickering Forest

Tales of a surprisingly large number

of our forebears who were poachers in Pickering Forest. Their archery skills

would foretell the legends of Robin Hood

and the English army at Agincourt

Having

travelled back in time from our contact with first individual Farndales of the

early thirteenth century, we now pick up the story from the thirteenth century

again, and travel forward in time from the thirteenth century. We will meet the

second generation, who were a little more restless than their fathers.

|

Poachers of Pickering Forest Podcast This

is a new experiment. Using Google’s Notebook LM, listen to an AI powered

podcast summarising this page. This should only be treated as an

introduction, and the AI generation sometimes gets the nuance a bit wrong.

However it does provide an introduction to the themes of this page, which are

dealt with in more depth below. |

|

Some

introductory music to set the scene. |

Within the

medieval records are significant number of our ancestors and their fellow

inhabitants of Farndale, who

were fined, outlawed and even excommunicated, for poaching and illegally

hunting, particularly within the Royal Forest of Pickering.

Scene 1 – The Control of the Royal

Forests

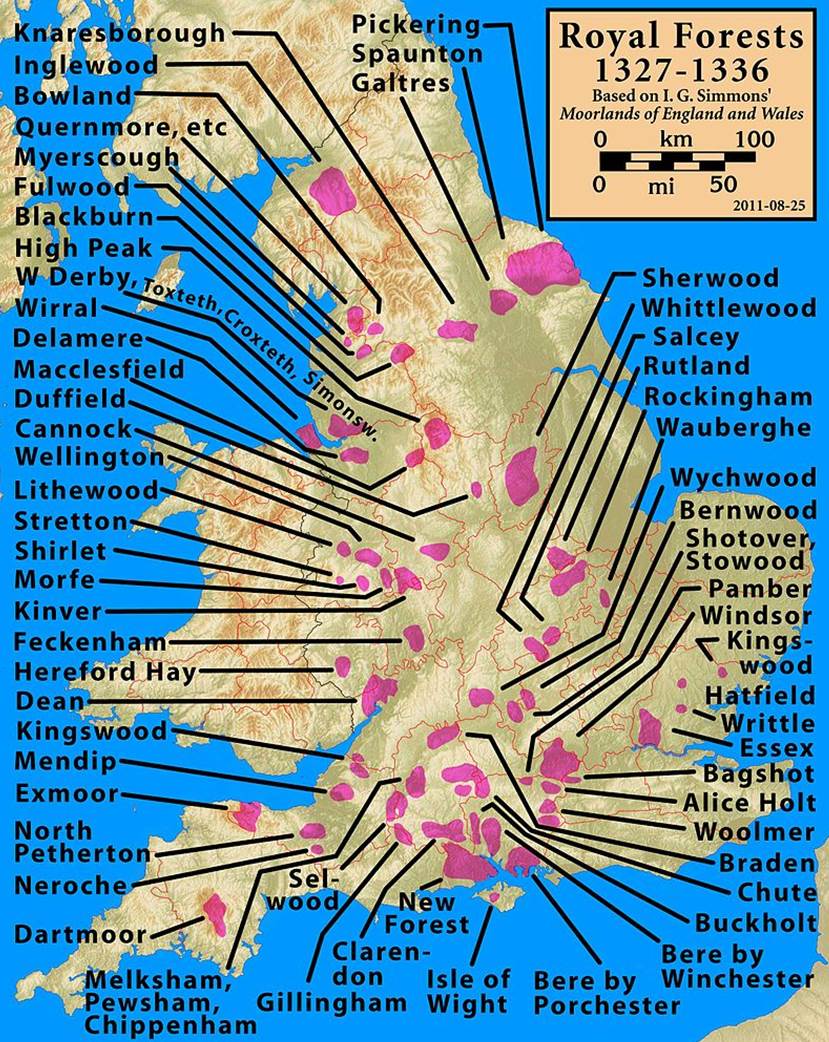

The Royal

Forest of Pickering

The Domesday Book

recorded that the manor of Pickering

included woodland which covered an area which was sixteen leagues long by four

leagues wide, about 55 miles by 14 miles. Before the Conquest the important

manor of Pickering was held by Earl Morcar, who we

met in Act 6 Scene 1.

By 1168 the

formation of the

honour of Pickering from the manors

of Pickering and Falsgrave, encompassing at that time

the parishes of Hackness and Scarborough, had joined the eastern forest

of Scalby to Pickering Forest, creating woodland extending from the River Seven

to the sea. The original forest of Pickering to the west bordered the forest of

Spaunton, at Lastingham,

which was in the custody of St. Mary's Abbey, York. To the east Scalby bordered

on the forest of Whitby, which in 1086

comprised over twenty-three square leagues of forest in the parishes of Whitby,

Sneaton, and Hackness,

overseen by the verderers of Whitby Abbey. Most of this land was forested, and

it ranged from the rich vale of Pickering in the south to the high moorlands of

northern areas such as Goathland, suitable mainly for sheep grazing.

In 1128,

Henry I had decreed that a huge area from York to the coast, including Ryedale

and Pickering,

should be reserved as Royal Forest, where hart, hind, wild boar and hawk were

preserved solely for the King. Serious punishments were dealt to those who

committed hunting offences, including the removal of body parts for taking of

deer.

A hart

is a male red deer and contrasts with a female hind. The word comes from the

Middle English word hert meaning deer. A soar

sometimes appears in the medieval documents and refers to a sow or female pig

or boar.

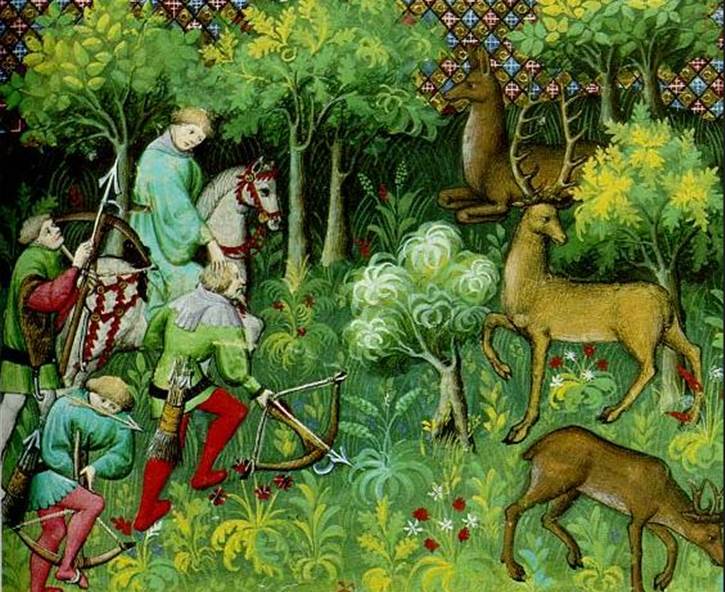

The forests

were an important element of the English psyche. Stories of hunting hart

in the forest were embedded in English culture.

The King

was wedded unto Dame Guenever at Camelot with great

solemnity. Just as all were sitting at the high feast that followed the

marriage, there came running into the hall a white hart, followed by a whole

pack of hounds with a great cry, and the hart went about the Table Round. At a

fierce bite from one of the dogs the hart made a great leap, and overthrew a

knight that sat at the table, and so passed forth out of the hall again, with

all the dogs after him. When they were gone the King was glad, for they made

such a noise, but Merlin said, "Ye may not leave this adventure so

lightly. Let call Sir Gawaine, for he must bring again the white hart."

"I

will," said the King, "that all be done by your advice." So Sir

Gawaine was called, and he took his charge and armed himself for the adventure.

Sir Gawaine was one of King Arthur's nephews, and had just been made a knight,

for he had asked of the King the gift of knighthood on the same day that he

should wed fair Guenever.

So Sir

Gawaine rode quickly forth, and Gaheris his brother rode with him, instead of a

squire, to do him service. As they followed the hart by the cry of the hounds,

they came to a great river. The hart swam over, and they followed after, and so

at length they chased him into a castle, where in the chief courtyard the dogs

slew the hart before Sir Gawaine and young Gaheris came up. Right so there came

a knight out of a room, with a sword drawn in his hand, and he slew two of the

greyhounds even in the sight of Sir Gawaine, and the remnant he chased with his

sword out of the castle.

When he

came back he said, "O my white hart, me repenteth that thou art dead, for

my sovereign lady gave thee to me, and poorly have I kept thee. Thy death shall

be dear bought, if I live."

(From the

stories of King Arthur)

Officers

were appointed to guard the royal forests and new administrators were appointed

such as the fee foresters and serjeantes. Some

of these officers were able to hold their land rent free in return for their

service as a forester.

Roger de Stuteville was licensed to have

hounds for taking wolf and hare throughout Yorkshire and Northumberland. The Mowbrays at Kirkbymoorside had

similar privileges.

When Henry I

established the Forest of Pickering as a

deer preserve he gave Guy the Hunter half the Aislaby

estate, in return for training the royal hound. Legend claims that two brothers

were given a falcon’s flight of land, for repelling a Scots invasion. Perhaps

the other brother was William of Aislaby, who had the

other half.

Walter Aspec in Ryedale forest gave three deer a year as a tithe

to Kirkham Priory.

King John

needed funds to pay for his wars in France. He sold off many of the royal

forests and there was significant deforestation in Ryedale. The remaining

forests were Galtres Forest, though reduced in size, Pickering Forest and the small forest of Farndale.

Pickering

Forest became part of the earldom of Lancaster from Henry Ill's reign.

Previously belonging to Simon de Montfort, the honour, castle, manor, and

forest of Pickering had been given in fee

by Henry III to his younger son, Edmund, in 1267, the first earl of Lancaster.

Edmund's son Thomas led the rebellion against Edward II, and following Thomas's

execution at Pontefract, Pickering and

its adjoining territories were confiscated by the crown. The forest and its

appurtenances were not restored to Thomas's brother Henry until the ascension

of Edward III.

Various

under-tenants and local landholders included Rievaulx Abbey, the Gilbertine

houses of Maltón and Ellerton Priory, and the

Hospitallers who held lands in the forest confiscated from the Templars.

Pickering was a private forest, but the

justices of Lancaster were still compelled to enforce the crown's forest law.

Even within

Pickering Forests, parks were allowed for leading nobility. We know that the Stutevilles began a campaign of clearing the

land in Farndale for agriculture from the early thirteenth century and

after paying a substantial sum, effectively revived their dominion over the Farndale lands. It seems likely

that there were areas of the larger Pickering Forest which were predominantly

the preserve of royal hunting grounds. The smaller forests in Farndale, and perhaps Spaunton seem to have been used for hunting, but were also

places of monastic grant lands and aristocratic economic activity. Initially

the great forested estates were of little worth except for hunting, but as the

elite landholders started to clear the forest for agriculture, an inevitable

tension arose between the landholders, but more particularly their grafting

tenants, and the upholders of the ancient rights of the forest.

|

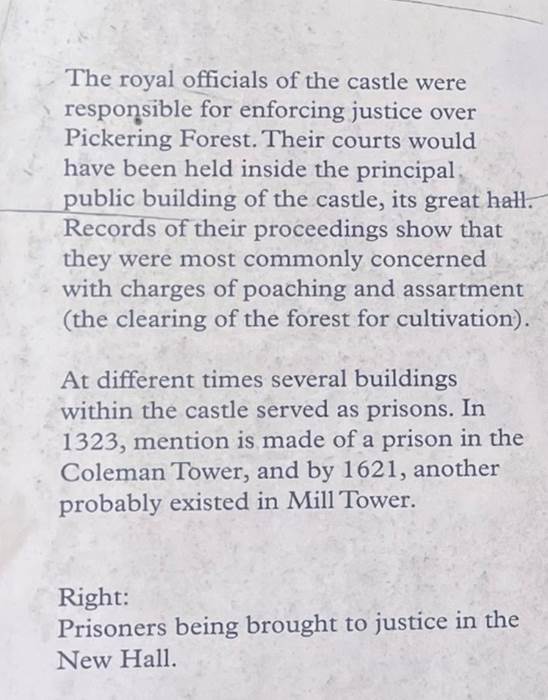

The sombre Norman castle of Pickering, where you will

be taken to the law court where our ancestors were fined, imprisoned,

outlawed and excommunicated |

|

A

study of the nature of poaching in Pickering Forest |

|

The Great Yorkshire Forest Drive A drive through Dalby Forest, the modern Pickering

Forest, where our forebears took game in contravention of forest laws, or

were caught and punished by the verderers and regarders of the forest |

|

Glance up at a remarkable medieval mural, which

includes archers who might remind us of our poacher ancestors |

Forest

Law

A complex

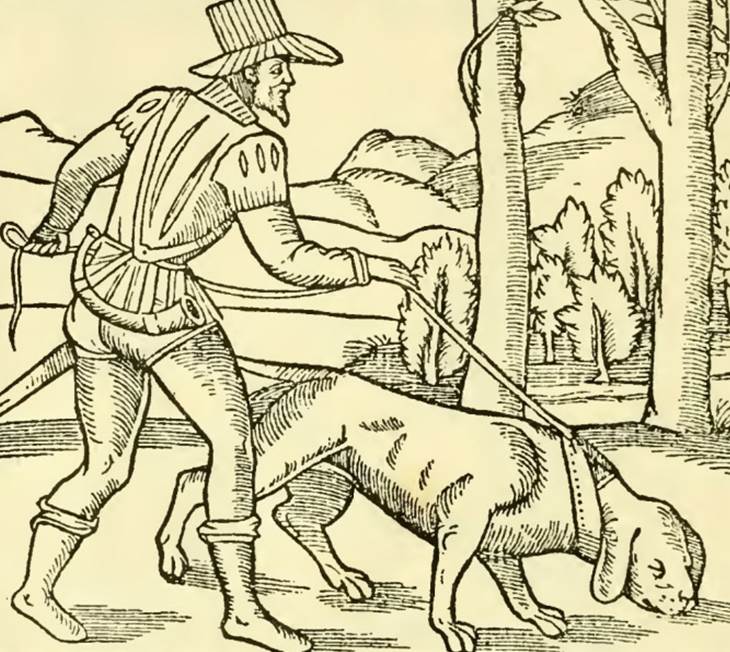

forest law developed, and large numbers of officials were appointed such as Verderers

and Regarders.

Verderers were forestry officials who

administered royal hunting areas which were the property of the Crown. The

office was developed in the Middle Ages to administer forest law on behalf of

the King. Verderers investigated and recorded minor offences such as the

taking of venison and the illegal cutting of woodland, and dealt with the

day-to-day forest administration. Verderers are still to be found in the

twenty first century in the New Forest,

the Forest of Dean, and Epping Forest, where they protect commoning

practices, and conserve the traditional landscape and wildlife. Verderers

were originally part of the ancient judicial and administrative hierarchy of

the vast areas of English forests and Royal Forests set aside by William the

Conqueror for hunting. The title Verderer comes from the Norman word vert

meaning green and referring to woodland.

The royal

forests were divided into provinces each having a Chief Justice who travelled

around on circuit dealing with the more serious offences.

Regarders were generally knights sworn to

carry out the regard of the Forest, which preceded the eyre. In old English law, they

were ancient officers of the forest whose task was to take a view of the forest

hunts. Regarders and agisters were responsible for guarding the

royal deer.

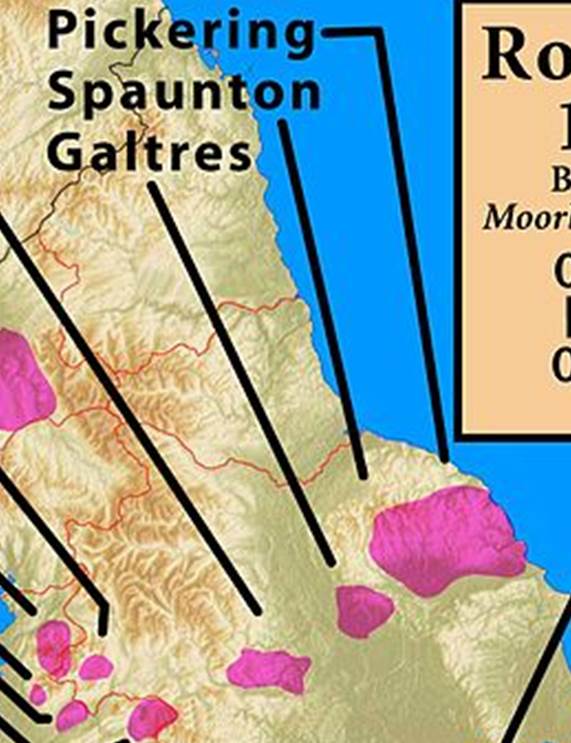

Old forest

customs were codified in Forest

Law, perhaps pioneered by the Assize of the Forest, also known as the

Assize of Woodstock, in 1184. Under the Norman kings, the royal forest grew

steadily, probably reaching its greatest extent under Henry II when around

thirty per cent of the country was set aside for royal sport. The object of the

forest laws was the protection of the beasts of the forest, including

red, roe, and fallow deer, and wild boar, and the trees and undergrowth which

afforded them shelter. The Assize of the Forest provided that none could carry

bows and arrows in the royal forest, and dogs had to have their toes clipped to

prevent them pursuing game. Savage penalties for any infringements were often

imposed. Discontent with the laws ensured that the forest became a major

political issue in John's reign.

The sixty

three clauses of Magna Carta in 1215 mainly did not deal with fundamental legal

principles but instead related to the regulation of feudal customs and included

clauses on the extent and regulation of the royal forest. Forestry regulation

culminated in the Charter

of the Forest in 1217. Only in the fourteenth century, when large areas

were deforested, did the political tension of the control of forests, start to

subside.

Officials of

Pickering forest used offences to raise income, by means such as pannage

payments for pigs taken into the woods. Ownership of large dogs was controlled.

Customary

rights to timber were overseen by the supervision of forest officers. These

rights came to be written as forest organisation became more elaborate. The

right to wood was referred to as bote. Pickering

folk could use green or dray wood for housebote, dry wood for firebote, or haybote

for fencing.

Forest

offences were numerous. Many saw poaching as a pastime. The nobility took to

hunting for sport, whilst more ordinary folk were often simply trying to

survive. We have records of large numbers of poaching parties from Farndale,

which we will explore soon, in more detail.

The

courthouse at Pickering Castle is the place where many of the Farndale

renegades were sentenced for forestry offences.

Scene 2 – the Farndale Poachers

The

Poachers from Farndale

In 1280, five

individuals of Farndale were indicted for poaching and paid bail, or had

bail paid for them by their families. From sureties of persons indicted for

poaching and for not producing persons so indicted on the first day of the Eyre

Court in accordance with the suretieship due to

Richard Drye. There follows a long list of names including,…..1s 8d from

Roger

son of Gilbert

of Farndale, bail from Nicholas de

Farndale, 2s from William

the Smith of Farndale, 3s 4d from John

the shepherd of Farndale, and 3s 4d from Alan

the son of Nicholas

de Farndale.

It seems

that a band of sons of the hard working first generation who had cleared new land for

agriculture Farndale, including Roger, William the Smith, John the Shepherd

and Alan, had gone hunting in the forest, but were caught, and had to be bailed

out by Nicholas

and perhaps his brother Gilbert.

A little

over a decade later, in 1293, Peter de

Farndale’s son Robert

was fined at Pickering Castle and Roger milne (“miller”) of Farndale, also a son of Peter

slew a soar in the forest.

|

c1265 to c1340 Roger slew a soar

in Pickering Forest in 1293 |

In a

separate incident, Roger milne (“miller”) of Farndale, son of Peter,

together with Walter Blackhous and Ralph Helved, all

of Spaunton on a Monday in January 1293, killed a soar and slew a hart with bows and arrows at some unknown

place in the forest. All were outlawed on 5 April 1293. Spaunton

is a short distance south of the entrance to Farndale, near Lastingham and Spaunton

Moor stretches north and was likely to have been treated as the same vicinity

as the Farndale lands. We will meet the restless Walter Blackhous

and Ralph Heved several more times. Ralph de Heved may be the same person as the Ralph de Capite of the 1301

Lay Subsidy levy.

The Forest

law impacted on the folk of Farndale even when they did not intentionally

pursue game. In 1310, Nicholas de Harland of Farndale was fined because his

cattle had strayed in the forest.

Richard

de Farndale and Thomas de Farndale were excommunicated in 1316 and the

church sought the assistance of the secular authority on 12 August 1316 when

the pride and continued contempt of the rebels could not be otherwise

suppressed by the church. Sentence was passed at Pickering Castle and this

might have been the consequence of an offence under canon law. The sentence of

Excommunication must have been devastating.

To the

Most Serene Prince, his Lord Edward by the Grace of God, King of England,

illustrious Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine, his humble and devoted

clerks, the Reverend Dean and Chapter of the Church of St Peter, York;

custodians of the spiritualities of the Archbishopric while the See is vacant;

Greetings to him to serve whom is to reign for ever. We make known to your

Royal Excellency by these presents that John de Carter, William of Elington, Adam of Killeburn, John

Porter, Hugh Fullo, Peter Fullo,

John of Halmby, Adam Playceman, John Foghill, Thomas Thoyman, Robert

the Miller, Adam of the Kitchen, Richard Mereschall,

John Gomodman, John Wallefrere,

Alan Gage, Henry Cucte, Nicholas of the Stable, John

the baker, Adam of Craven, John son of Imanye,

Michael of Cokewald, Thomas of Morton, John of Westmerland, Thomas of Bradeford, Adam of Craven, John of Mittelhaue, John called Lamb, William Cowherd, Simon of Plabay, William the Oxherd, Henry of Rossedale,

John of Carlton, Peter of Boldeby, Thomas of Redmere, Walter of Boys, William of Fairland, John of Skalton, John of Thufden, Henry

the Shepherd’s boy, John of Foxton, Thomas

of Farndale, John of Ampleford, John Boost,

Roger of Kerby, John of Stybbyng, William of Carlton,

Richard of Kilburn, Adam Scot, Peter of Gilling, John of Skalton,

Stephen of Skalton, Richard

of Farndale, Richard of Malthous, John the

Oxherd, Robert of Rypon, Walter of Fyssheburn, Adam of Oswadkyrke,

William of Everley, Hugh of Salton, William Robley, William of Kilburn,

Geoffrey the Gaythirde, John of the Loge, Robert of Faldington, Nicholas of Wasse, William of Eversley, Robert

of Habym, John of Baggeby

and William Boost, our Parishioners, by reason of their contumacy and

offence were bound in our authority by sentence of greater

excommunication, and in this have remained obdurate for 40 days and more,

and have up to now continued in contempt of the authority of the Church.

Wherefore we beseech your Royal Excellency, in order that the pride of these

said rebels may be overcome, that it may please you to grant Letters,

according to previous meritorious and pious custom of your Realm, so that the

Mother Church may, in this matter, be supported by the power of Your Majesty.

May God preserve you for His Church and people. Given at York 12 August 1316.

|

Richard and Thomas

of Farndale Two brothers who

were excommunicated for poaching and contempt of the authority of the church

in 1316 |

|

Excommunication in the Middle Ages

There is a podcast in the Gone Medieval series on the impact, or sometimes

lack of impact, of excommunication. King John was excommunicated in 1307 and initially

at least ignored it. |

By the

1320s, poaching offences, involving many Farndale inhabitants amongst large

numbers, started to mount in the records.

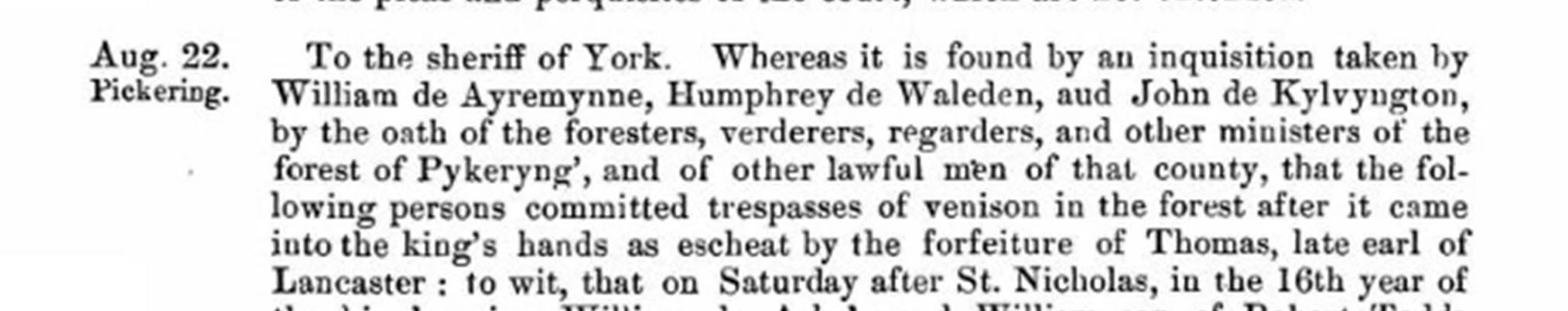

On 22 August

1323 an edict was declared at Pickering

by the forest officials. To the sheriff of York. Whereas it is found by an

inquisition taken by William de Ayremynne, Humphrey

de Waleden, and John de Kylvyngton,

by the oath of the foresters, verderers, regarders, and other ministers at

the forest of Pickering, and of other lawful men of that county, that the

following persons committed trespass of venison in the forest after it came

into the King's hands as escheat by forfeiture of Thomas, late earl of

Lancaster... that on Friday the morrow of Martinmas, in the aforesaid year,

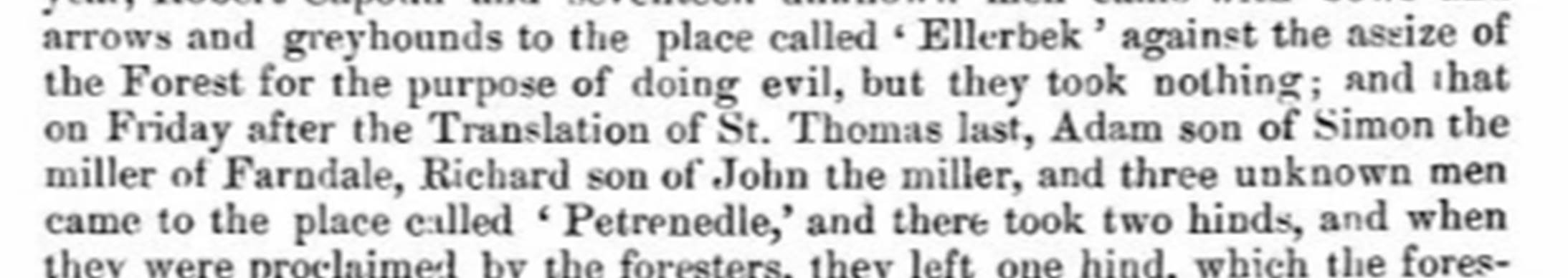

Robert Capoun, knight, Robert son of Marmaduke de Tweng, and eight unknown men with bows and arrows and four

greyhounds came to a place called ‘Ellerbek’, and there took a hart and two other deers (feras), and carried the venison away; and that on Thursday

before the Invention of the Holy Cross, in the aforesaid year, Robert Capoun and seventeen unknown men came with bows and arrows

and greyhounds to the place called ‘Ellerbek’ against the assize of the forest

for the purpose of doing evil, but they took nothing; and that on Friday after

the Translation of Saint Thomas last, Adam,

son of Simon the

Miller of Farndale, Richard

son of John

the Miller, and three unknown men came to a place called ‘Petrenedle’, and there took two hinds, and when they were

proclaimed by the foresters, they left one hind, which the foresters

carried to Pykeryng castle and the said malefactors

carried the other away with them;... the King orders the sheriff to take with

him John de Rithre, and to arrest all the aforesaid

men and Juliana, and to deliver them to John de Kylvynton,

keeper of Pykeryng castle, whom the king has ordered

to receive them and to keep them in prison in the castle until further orders.

In July 1323, Adam, son of Simon the Miller was fined 25s 8d for taking two hinds.

The 1301

subsidy was levied on those who paid as little as only threepence. The list

of the taxpayers in Farndale

in the 1301 record can be reconciled with some of the poachers, such as Simon the Miller,

but not all. Perhaps this suggests that there were tenants in Farndale who, for

some reason, or other escaped paying Edward's levy. Perhaps though many were

the sons of the Farndale tenants, and so didn’t appear in the subsidy list.

John de

Farndale was released

from excommunication at Pickering Castle on 23 February 1324. To the

Most Serene Prince, His Lord Edward, by the Grace of God, King of England, Lord

of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine, William by Divine permission Archbishop of

York, Primate of England, Greetings in him to serve who is to reign for ever.

We make known to Your Royal Excellency, by these presents that William de Lede

of Saxton, John of Farndale and John Brand of Howon,

our Parishioners, lately at our ordinary invocation, according to the custom

of your Realm, were bound by sentence of greater excommunication and,

contemptuous of the power of the Church, were committed to Your Majesty’s

Prison for contumacy and offences punishable by imprisonment; and have

humbly done penance to God and to the Church, wherefore they have been deemed

worthy to obtain from us in legal form the benefit of absolution. May it

therefore please Your Majesty that we re-admit the

said William, John and John to the bosom of the Church as faithful members

thereof and order their liberation from the said prison. May God preserve you

for His Church and the people. Given at Thorpe, next York, 9 April 1324.

The date of the following extract from the Coucher Book, is

probably from about 1330. Richard Mosyn, of that

part of Rossedale which belongs to the Abbot of S.

Mary's (i.e. Rosedale West), William Troten of Spaunton, Roger del Mulne of Farndale, Robert son of Peter of Rossedale, Walter Blackhous of

Farndale, went on a Monday in January to some unknown place within the

forest and killed a soar and slew a hart with bows

and arrows. All are outlawed.

The Coucher Book also tells of how Thomas de Hamthwaite,

Robert de Bolton, Richard of Helmsley, John de Skipton, Robert Moryng, Abraham Milner, Stephen Moye, and Peter son of

Henry, with others unknown, on Thursday, 7th of March, 1331, went to a place

called Hamclifbek, with two leporariis

(gazehounds or greyhounds), and belonging to John de Kilvington and Robert

Spink, and with bows and arrows, and there slew one soar and one hind and one

stag, and were fined, etc. In the same folio we have an account of how Roger

son of Emma, John de Bordesden, Robert Moryng, John son of William Fabri (Smith) of Farndale, Robert Stybbing,

and William Bullock, about the feast of S. Bartholomew, captured one hind

and one calf at Rotemir and Hugh de Yeland and John de Yeland, Thomas Hampthwait,

William de Langwath, Peter son of Henry Young,

William de Hovingham, forester of Spaunton, William

Burcy (or Curcy), Robert de Miton,

sergeant of Normanby, and six others unknown, captured at Leasehow,

with bows and arrows and hounds, a young hart.

In September

1332, Robert

son of Simon of

Farndale, in company with four others "hunted a hart

and carried it off''. Robert's four companions were fined, he himself being

outlawed. Robert

Farndale, son of Simon the miller of

Farndale and Robert

Farndale, son of Peter of

Farndale, were both fined for poaching at Pickering Castle in 1332. Pleas

held at Pickering on Monday 13 Mar 1335 before Richard de Willoughby and John

de Hambury. The Sheriff was ordered to summon those

named to appear this day before the Justices to satisfy the Earl for their

fines for poaching in the forest of which they were convicted before the

Justices by the evidence of the foresters, venderers

and other officers. They did not appear and the Sheriff stated that they

could not be found and are not in his bailiwick and he had no way of

attacking them. He was therefore ordered to seize them and keep them safely

so that he could produce them before the Justices on Monday 15 Mar 1335. A long

list of names follows including……Robert filium

Simonis de Farndale, Rogerum de milne

de Farndale, Robertum, filium

Petri de Farndale.

|

c1266 to c1340 Robert was fined

for poaching in Pickering Forest in 1293 and 1332 |

Nicholas

of Farndale, gave bail for Roger

son of Gilbert

of Farndale who had been caught poaching in 1334 and 1335.

1334 was the year of the Eyre Court. It was therefore time to catch up

with the Farndale misbehaviour of the preceding years. A mainpernor

was a person who gave a guarantee that a prisoner would attend court. Westgill is the area of Farndale around West Gill Beck

which flows down to the River Dove at Low Mill. The folk of Farndale had

clearly been out in significant numbers to engaging in poaching. The hearing

dealt with offences of some antiquity, the reference to the seventeenth regnal

year of Edward I indicating an offence that took place in 1288 to 1289. So

these records were catching up with several years of activity in the forest.

Fines, amercements and issues of

forfeitures at Pikeryng before Richard de Wylughby

[Willoughby], Robert de Hungerford and John de Hambury,

itinerant justices assigned to take the pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of

Lancaster, of Pickering … Roger, son of Gilbert de Frandale [Farndale], one of the mainpernors of John, son of Albe,

indicted of hunting. … John Alberd,

another mainpernor of the same Robert, son of

Richard de Westgill, indicted of hunting. The

same John Alberd, one of the mainpernors

of John, son of Richard de Westgill, indicted

of hunting. John, son of Walter, one of the mainpernors

of Robert, son of Richard de Westgill, indicted of

hunting. John le Shephirde of Farndale, one of the mainpernors

of John, son of Richard de Westgill, indicted of

hunting. Alan, son of Nicholas de Farndale, one of the mainpernors

of Richard, son of John de Farndale, indicted of hunting. The same Alan, son of Nicholas de Farndale, one of the mainpernors

of Adam, son of Simon the miller of Farndale, indicted of hunting. Nicholas Laverok, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John de Farndale, indicted of hunting. The same

Nicholas Laverok, one of the mianpernors

of Adam, son of Simon the miller, indicted of hunting. John, son of John the

miller, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale, indicted of hunting. The same John, son of John the miller, one of the mainpernors

of Adam, son of Simon the miller, indicted of hunting. William le Smyth of

Farndale, one of the mainpernors of Robert,

son of Richard de Westgill, indicted of hunting. The same William le Smyth of

Farndale, one of the mainpernors of John,

son of Richard de Westgill, indicted of hunting. John, son of John the miller, one of the mainpernors

of Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale, indicted of hunting. The same John,

son of John the miller, one of the mainpernors of

Adam, son of Simon the miller, indicted of hunting. Nicholas Brakenthwayt,

one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale, indicted of hunting. The same Nicholas Brakenthwayt, one of the mainpernors

of Adam, son of Simon the miller, indicted of hunting. Alan de Braghby, one of the mainpernors

of Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale, indicted of hunting … Nicholas de Repyngale [Rippingale], one of the mainpernors

of Richard, son of John, and Adam, son of Simon the miller of Farndale, indicted of hunting. The same Alan de Braghby, one of the mainpernors of Adam, son of Simon the miller, indicted of

hunting. John de Braghby, one of the mainpernors of Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale, indicted of hunting. … Pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of Lancaster, of Pikeryng [Pickering], held at Pickering before Richard de Wylughby [Willoughby], Robert de Hungerford and John de Hambury, justices itinerant on this occasion assigned to

take pleas of the said forest in Yorkshire: People mentioned … Adam, son of Simon the miller of Farndale, and Richard, son of John the miller: It is presented that they and

three unknown men, on Friday next after the feast of the Translation of St

Thomas 17 Edw I, came in the said forest in a place called Petroneldel,

and there took two deer. And when they had been proclaimed by the

forester, they sent away one deer, which the foresters carried to the castle of

Pikeryng [Pickering], and another deer the wrongdoers

carried away with them and thereupon did their will. They do not now come, but

it is witnessed that they are staying in the country. Therefore the sheriff is

ordered to make them come … John, son of Richard de Westgil of Farndale, and Robert, his brother: On

Sunday the eve of the Nativity of St John the Baptist 18 Edw II, they came in

the said forest in a certain place called Soterlund,

with one mastiff, bows and arrows, and took there one fawn and carried away the

game with them and thereupon did their will. They do not now come, nor were

they previously attached, but it is witnessed that they are staying in the

country. Therefore the sheriff is ordered to cause them to come.

… Pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of Lancaster, of Pikeryng [Pickering], held at Pickering before Richard de Wylughby

[Willoughby], Robert de Hungerford and John de Hambury,

justices itinerant on this occasion assigned to take pleas of the said forest

in Yorkshire: … Richard Moryn of Rossedale [Rosedale]

on the behalf of the abbot of St Mary, William Trotan

of Spaunton, Roger del Mulne of Farndale, Robert, son of Peter of the same, Walter Blakhous of

the same, and Ralph de Heued of the same: On Monday next after the feast of the Epiphany, they came in the

forest in an unknown place with bows and arrows and killed one four-year-old

buck and hunted one stag and carried away with them the game and thereupon

did their will. They have not now come, etc. Therefore the sheriff is ordered

to cause them to come … Roger son of Emma, John de Bordesden,

Robert Moryng, John, son of William the Smith of Farndale, Robert Stybbyng,

and William Bullok: Around the feast of St Botolph 10 Edw [III], they came in the forest

in a place called Rotemir [Rutmoor],

and took there one deer and one calf, and carried away that game …. Roger Sturdy, Thomas de Hippeswell, Robert, son of Simon de Farndale, John le Caluehird

and Peter son of Henry: On Thursday next before Michaelmas 6 Edw III, they came

in the said forest in a place called Flaskes and

there hunted one stag and took it away with them. They have not now come, nor

were they previosuly attached, but it is witnessed

that they are living in the country. Therefore the sheriff is ordered to make

them come … Richard, son of John the miller of Farndale, and Adam, son of Simon the miller of Farndale: After they trespassed about hunting

in this forest, Richard and Adam were sent away by the mainprise of Nicholas de

Repynghale [Rippingale], Adam, son of Nicholas de Farndale, Nicholas Laverok,

John, son of John the miller, Nicholas de Brakenthwayt

[Brackenthwaite[, Alan de Wraghby

[Wragby] and John Wraghby of Farndale, who mainperned to have them on the first day of the eyre, and

they so not now have them, etc … John, son of Richard de Westgille of Farndale: John was sent away by the mainprise

of William le Smyth of Farndale, Richard de Westgill,

John le Shephird of Farndale, John Alberd

of the same, Nicholas, son of Walter of the same, John del Heued of the

same, and Robert de Westgill, who mainperned

to have him on the first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc. Robert, son of Richard de Westgill of

Farndale: Robert was sent away by the mainprise of William le Smyth of Farndale, John, son of Walter of the same, John Alberd of the

same, and Nicholas, son of Walter of the same, who mainperned to

have him on the first day of the eyre, and they do not now have him, etc … John son of Abba: John was sent away by the mainprise of Roger, son of Alfred de Farndale, Roger, son of Gilbert of the same, Richard de Beverle [Beverley] of the same, William Kyng of the same, John de Hoton of

the same, Thomas Makand, Hugh the clerk of Cropton,

William de Birkheued of Hartoft, Henry del Tung,

Peter son of Gervase, Hugh Broun [Brown], smith, and William Hare, who mainperned to have him on the first day of the eyre, and

they do not now have him, etc.

In 1335, on the Pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of

Lancaster, of Pikeryng, held at Pickering before the said Richard de Wylughby

[Willoughby] and John de Hambury, justices itinerant

on this occasion assigned to take pleas of the said forest in Yorkshire there was a very long list of names which included Robert, son of Simon de Farnedale [Farndale], Roger del Milne of Farnedale [Farndale], Robert, son of Peter de Farndale, Walter Blachose, regarding whom the sheriff

is ordered to cause the aforesaid people to come before the justices here on

this day to make satisfaction to the earl about their redemption for trespasses

of hunting made in this forest, whereof they are convicted before the said

justices by the foresters, verderers and other ministers. And they have not

come.

The

unbalanced nature of medieval justice is illustrated by the fact that Lady Blanche Wake, whose tenants

all these men were, was convicted in 1335 taking a soar

and two hinds and carrying them off for her own use. Afterward continued

the record, the Earl , that is the Earl of Lancaster, directed his

Justices to stay all further proceedings against the Lady Blanche, wherefore

they stayed proceedings.

In 1336 Fines

at Pikeryng before Richard de Wylughby

[Willoughby] and John de Hambury were imposed on

another long list of names which included John, son

of William

fabri of Farndale. William was the fabri, or blacksmith of Farndale.

John de

Farndale was

bailed for poaching at Pickering before Richard de Wylughby

and John de Hainbury on Monday 2 December 1336.

William,

smith of Farndale

was reported to have come hunting in Lefebow with bow

and arrows and gazehounds, or greyhounds, on Monday 2 December 1336.

|

c1295 to c1370 William was the poacher of a hind and a calf in 1330 and repeat

offender in 1336 |

In 1337 on Pleas of the forest of

Henry, earl of Lancaster, of Pikeryng, held at

Pickering before the said Richard de Wylughby

[Willoughby] and John de Hambury, justices itinerant

on this occasion assigned to take pleas of the said forest in Yorkshire

another long list of names was presented including Robert, son of Simon de Farnedale, Roger del Milne of Farnedale, Robert, son of Peter de Farndale, Walter Blachose, Ralph del Heued, and William de Ergom [Argam], chaplain, regarding whom the sheriff is

ordered to cause the aforesaid people to come before the justices here on this

day to make satisfaction to the earl about their redemption for trespasses of

hunting made in this forest, whereof they are convicted before the said

justices by the foresters, verderers and other ministers. And they have not

come.

In 1338 on the Pleas of the forest of Henry, earl of

Lancaster, of Pikeryng, held at Pickering before the said Richard de Wylughby

[Willoughby] and John de Hambury, justices itinerant

on this occasion assigned to take pleas of the said forest in Yorkshire, another long list of names included Robert, son of Simon de Farnedale [Farndale], Roger del Milne of Farnedale [Farndale], Robert, son of Peter de Farndale, Walter Blachose, Ralph del Heued, and William de Ergom [Argam], chaplain, regarding whom once again the

sheriff is ordered to cause the aforesaid people to be exacted from county to

county, until, etc, they are outlawed, if they do appear. And if they do

appear, he is then to take them, in such a way that he has their bodies here at

this day to make satisfaction to the earl about their redemption for trespasses

of hunting whereof they are convicted before the said justices by the

foresters, verderers and other ministers.

Clearly

efforts were made to apprehend Robert,

son of Simon of

Farndale, Roger

the miller of Farndale, Robert

son of Peter of

Farndale, Walter Blackhaus, Ralph Heved and apparently even the chaplain in 1335 and 1337 and

in 1338 they were outlawed with orders that they be apprehended and brought

before the forest officers if found.

In English

law, oyer and terminer, from the French oyer et terminer, literally

means to hear and to determine. It was one of the commissions by which a

judge of assize sat. By

the commission of oyer and terminer the commissioners, the judges of assize,

along with others also listed, were named in the commission, and commanded to

make diligent inquiry into all treasons, felonies and misdemeanours whatever

committed in the counties specified in the commission, and to hear and

determine the same according to law. The inquiry was by means of a grand jury.

After the grand jury had found the bills of indictment submitted to it, the

commissioners proceeded to hear and determine by means of the petit jury.

The words oyer and terminer were also used to denote the court that had

jurisdiction to try offences within the limits to which the commission of oyer

and terminer extended.

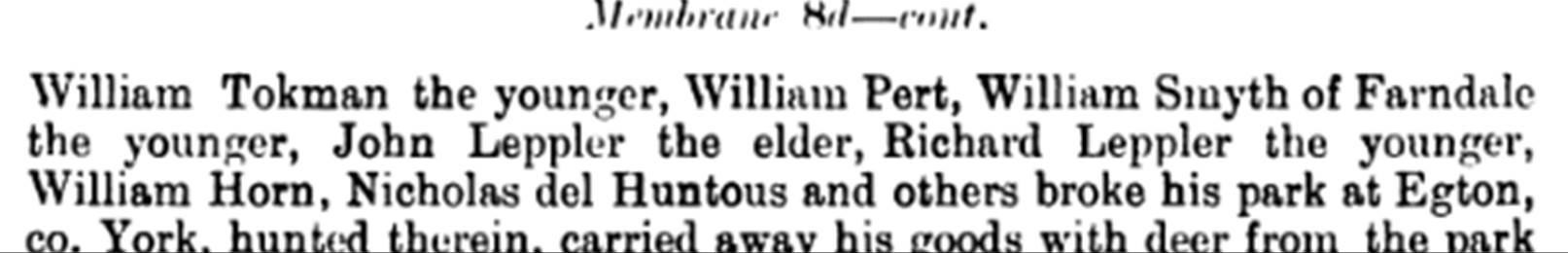

In 1347, the

twenty first regnal year of Edward III, at Westminster, Commission of Oyer

and terminer was ordered to Henry de Percy, Thomas de Rokeby, William

Basset, William Malbys, William de Broclesby, Thomas de Fencotes and

Thomas de Seton, on complaint by the same Peter that Edmund de Hastynges against a number of individuals including William

Smyth of Farndale the younger who had broke

his park at Egton, Co York, hunted therein, carried away his goods with deer

from the park and assaulted his men and servants, whereby he lost their service

for a great time. By fine of 1 mark. There was also a reference to Richard Ruttok of Farendale in the long

list of names.

The value of

a mark was 13s 4d. There is a webpage about the value

of medieval money.

Again, on 17

January 1348 at Westminster, there was a commission of oyer and terminer

to a long list of names including William

Smyth of Farndale the younger and Richard Ruttok

of Farendale for breaking in to the park at

Egton, hunting and carrying away the property of the owner with deer, and for

assaulting the owner’s men and servants causing their inability to work for a

long time, for which they were fined 1 mark.

Breaking the

close refers to the unlawful entry to another person’s land. It is common law

trespass.

In the

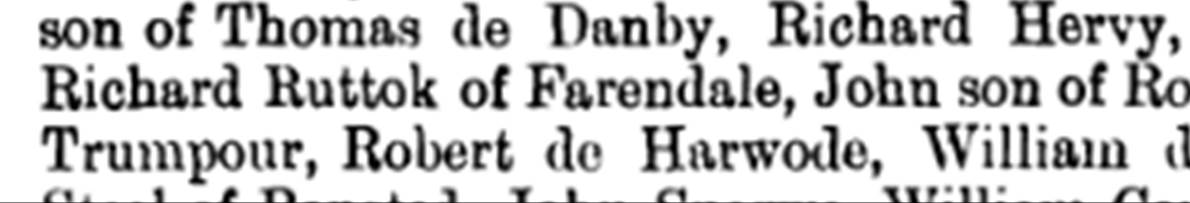

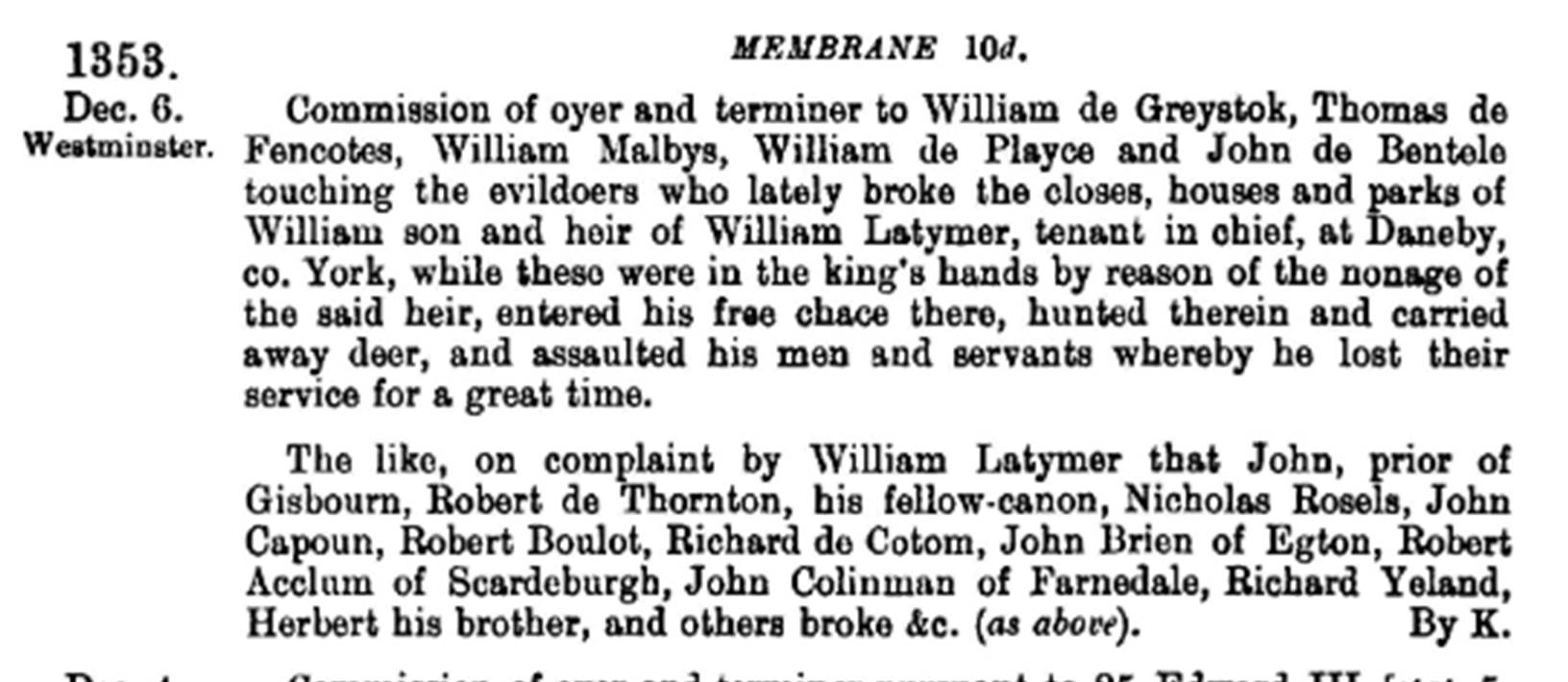

twenty seventh regnal year of Edward III, on 6 December 1353, Commission of

oyer and terminor was ordered to William de Greystok … touching the evildoers who lately broke

to closes, houses and parks of William son and heit

of William Latymer, tenant in chief at Daneby, co York, while these were in the king’s hands by reason of

the nonage of the said heir, entered his free chace there, hunted therein and carried away deer, and assulated his men and servants whereby he lost their

service for a great time. The like complaint by William Latymer that John,

prior of Gisborne, Robert de Thornton, his fellow canon, Nicholas Rosels … John Colinman of Farnedale …

and others broke etc (as above).

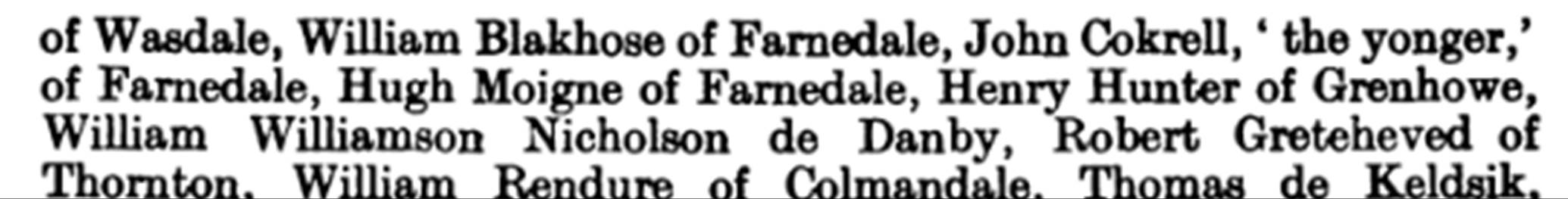

William Blakhose of Farndalde, John Cokrell

the Younger of Farnedale and Hugh Moigne of Farnedale were all fined 20s for poaching fish in 1366, in the

fortieth regnal year of Edward III. On February 10, At Westminster.

Commission of Oyer and Terminer to John Mourbray,

Thomas de Ingleby … on complaint by Peter de Malo Lacu, ‘le sisme’,

that William Birkhead of Wasdale …William Blakhose

of Farndale, John Cokrell the younger of Farndale….

broke park at Grenhowe and entered his free warrens

at Semar in Clyvelande, Whorleton

in Clivelande, Seton in Whitebystrande,

Boynton ‘on the Wolde’ and Killyngwyk by Braken, co York, hunted in these,

fished in his stews and other several fisheries there, took fish therein, and

carried away fish as well as other goods and hares, conies, pheasants and

partridges, and assaulted and wounded his servants. For 20s paid in the hanaper.

A hanaper

is a drinking vessel, so perhaps there was a collection pot for the fines.

Violent

poaching and cattle rustling

William

Blackhous was involved in another incident in

1366 involving Roger milne of Farndale.

Seemingly on something of a rampage, in the following year William

Blackhouse and William of Farndale trespassed, hunted, felled trees, fished,

trod down and ate corn and assaulted the servants of the complaining knight,

William Latimer. In the forty first regnal year of Edward III, on 8 November

1367, at Westminster, Commission of Oyer and Terminer was ordered to John

Mourbray, Thomas de Ingleby … on complaint by

William Latymer, knight, that whereas the king lately took him, his men, lands,

rents and possessions into his protection while he stayed in the king’s service

in the parts of Brittany, Master John de Bolton, clerk, Thomas de Neuton, chaplain, William Rede … William of Farndale

… William Blakehose of Farndale … broke

his closes at Danby, Leverton, Thornton in Pykerynglith,

Symnelyngton, Scampton, Teveryngton

and Morhous, Co York, entered his free chace at Danby and his free warren at the remaining places,

hunted therein without licence, felled his trees there, fished in his several

fishery, took away fish, trees, deer from the chace,

hares, conies, pheasants and partridges from the warren departured,

trod down and consumed the corn and grass there with certain cattle and

assaulted and wounded his men and servants. By K And be it remembered that the

said William has granted the king a moiety of all the profit which he shall

recover for damages by pretext of the said commission.

On 6 March

1370, William Latimer’s complaint was reheard since at Westminster. Commission

of Oyer and Terminer was ordered to John

Mourbray, Thomas de Ingleby … on complaint by

William Latymer, knight, that whereas the king lately took him, then stayed in

his service in Brittany, and his men,

lands, rents and possessions into his protection, into his possession for a

certain time, Master John de Bolton, clerk, Thomas de Neuton,

chaplain, William Rede …John Cockerell of Farndale … William Blakhose of Farndale … broke his closes at Danby,

Leverton, Thornton in Pykerynglith, Symnelyngton, Scampton, Teveryngton

and Morhous, and entered his free chace

at the said town of Danby and his free warren at the remaining places, hunted

in these, felled his trees there, fished in his several fishery there, carried

away his fish, trees, deer from the chace, hares,

conies, pheasants and partridges from the warren, trode

down and consumed with cattle his crops and assaulted his men and servants.

7 May 1370,

at Westminster, a pardon was given to William

Farndale of Caleys of the King's suit for the

death of John de Spaldyngton, whereof he had been

indicted, and he was pardoned of any consequent outlawry. Spaldington

is a village about twenty kilometres southeast of York and Caleys

is probably a place in that vicinity.

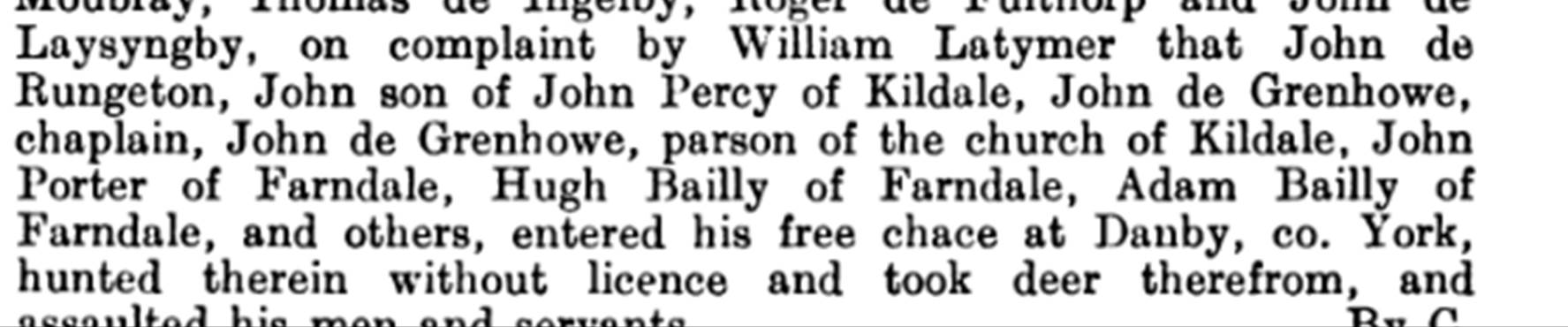

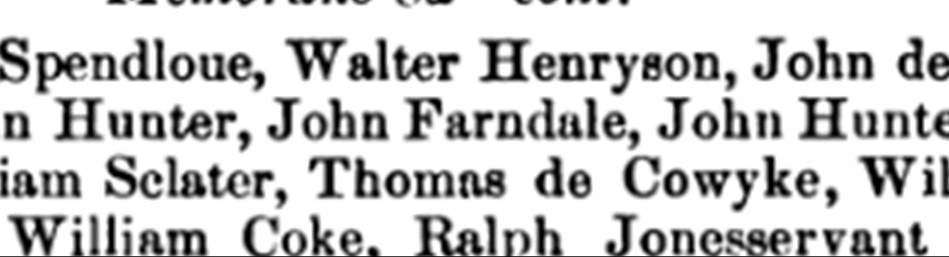

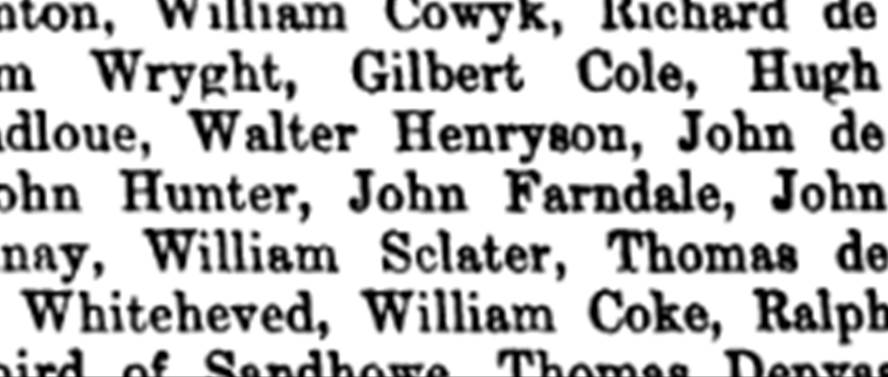

On 20

November 1372 at Westminster, Commission was given to Ralph de Hastynges, John Moubray, Thomas de Ingleby, Roger de Fulthorp and John de Laysyngby, on

complaint by William Latymer that John de Rungeton,

John son of John Percy of Kildale, John de Grenhowe,

chaplain, John de Grenhow, parson in the church of

Kildale, John Porter of Farndale, Hugh Bailly of Farndale, Adam

Bailly of Farndale, and others, entered his free chace

at Danby co York, hunted therein without licence and took deer therefrom, and

assaulted his men and servants. By C.

The hapless

knight William Latimer was suffering once again at the whims of the reckless

folk of Farndale.

Things seem

to be getting out of hand when on 10 December 1384, at Westminster, a

Commission of Oyer and Terminer related to John Farndale and others who broke their close,

houses and hedges at Wittonstalle and Fayrhils, Co Northumberland and seized 30 horses, 20 mares,

100 oxen and 100 cowes valued at £200 and carried

them off with goods and chattels, assaulted his men, servants and tenants and

so threatened them that they left his service.

The scale of

the rustling expedition is breathtaking. Perhaps the poaching tradition,

initially driven by famine and hunger, had turned into something akin to

organised crime, a foretaste of the Border

Reivers who were starting to harass the border areas at about the same

time.

|

c1365 to c1450 John took poaching

to a new scale when he was involved in a significant cattle and horse

rustling expedition in 1384 |

On 21 August

1385 at Durham, Commission of Oyer and Terminer was ordered to investigate an

allegation that John

Farndale, and others broke their close, houses and hedges at Wittonstalle and Fayrhils, Co

Northumberland.’ John seems to have got a taste for his adventures north.

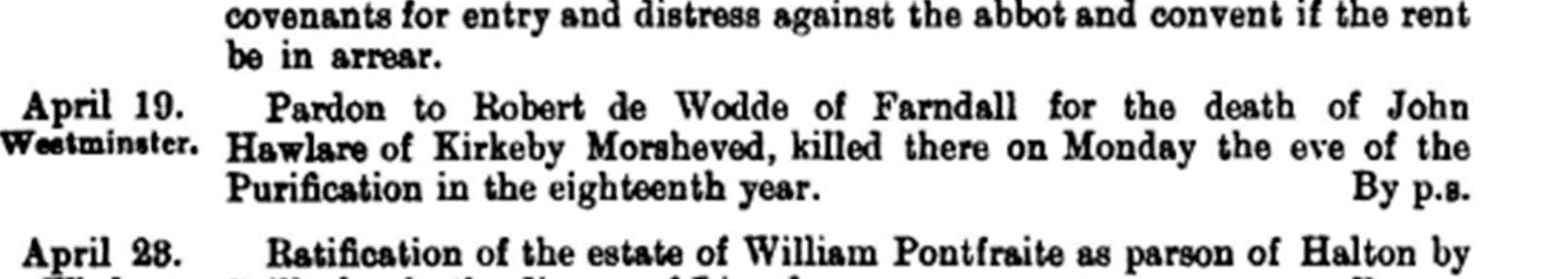

On 19 April

1396, a pardon was given to Robert

de Wodde of Farndale, for the death of John Hawlare

of Kirby Moorseved, killed there on Monday, the eve

of the Purification in the eigtheenth year. The

eighteenth year must have been a reference to the eighteenth regnal year of

Richard II, so the death must have occurred on 1 February (the eve of

Candlemas, also known as the Purification) 1395.

There was another

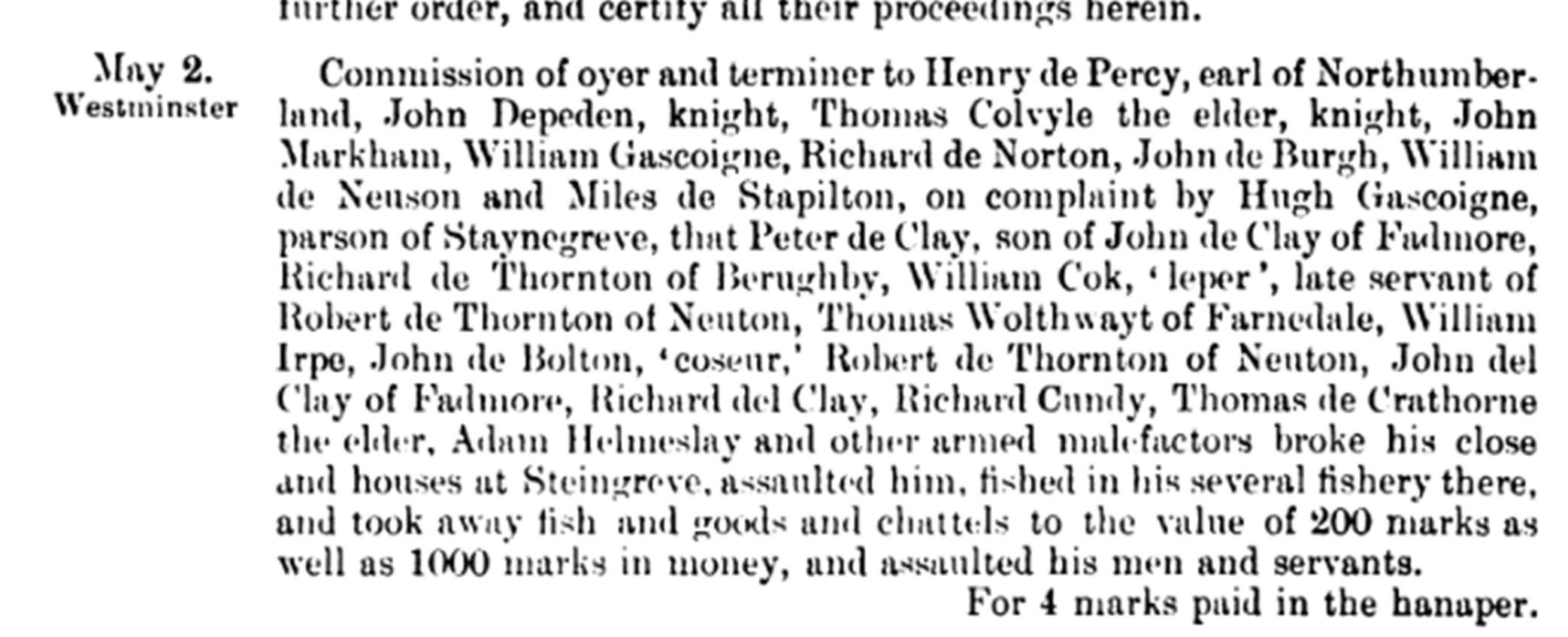

serious armed robbery on 2 May 1398. At Westminster. Commission of Oyer

and Terminer to Henry de Percy, earl of Northumberland, John Depeden, knight, Thomas Colvyle

the elder, knight, John Markham, William Gascoigne, Richard de Norton, John de

Burgh, William de Nenson, and Miles de Stapilton, on complaint by High Gascoigne, parson of Staynegreve, that Peter de Clay, son of John de Clay of Fadmore, Richard de Thornton of Neuton,

Thomas Wolthwayt of Farnedale,

William Irpe, John de Bolton, ‘coseur’,

Robert de Thornton of Neuton, John del Clay of Fadmore, Richard del Clay, Richard Candy, Thomas de

Crathorne the elder, Adam Helmeslay, and other

armed malefactors broke his close and houses at Steingreve,

assaulted him, fished in his several fishery there, and took away his fish

and goods and chattels to the value of 200 marks as well as 1000 marks in

money, and assaulted his men and servants. For 4 marks paid in the hanaper.’

This was

armed robbery at scale, it seems. Four marks into the collection pot doesn’t

quite seem to do justice to the scale of the crime.

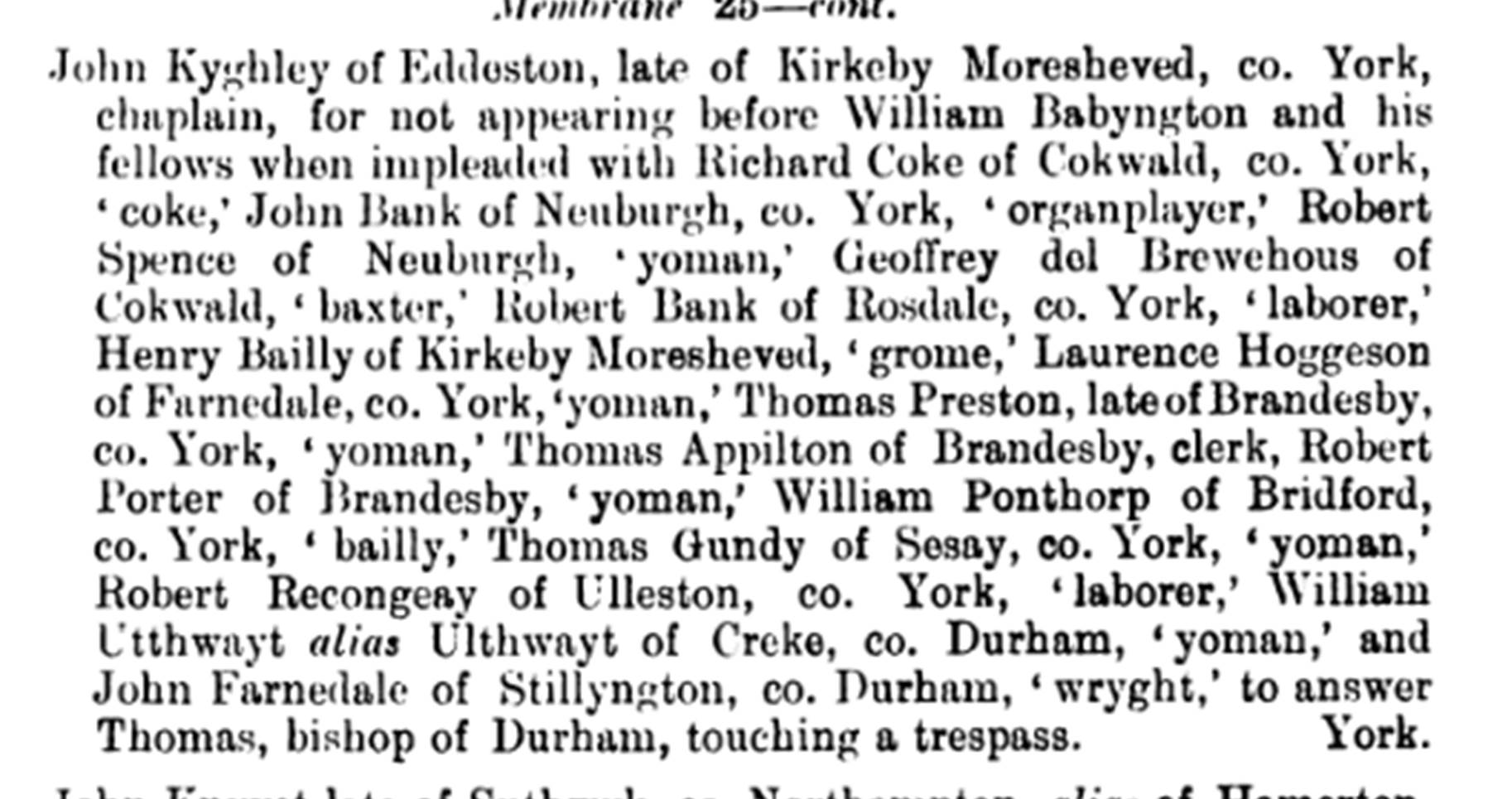

On 16 April

1445 at Westminster…..for not appearing before William Babynton

and his fellows when impleaded with Richard Coke of Cokewald,

Co York…. Lawrence Hoggeson of Farndale and John Farndale

of Stillyngton Co Durham, wright, to answer

Thomas Bishop of Durham touching trespass.

Robin

Hood

There is a

Sky documentary, the British,

of which Episode 2, People

Power, depicts two brothers, called Philips, poaching in Pickering Forest.

The Philips brothers in the Sky documentary might as well have been Farndales.

The documentary observes that it was stories of folk such as the poachers of

Pickering Forest who, a few centuries later, would inspire the tales of Robin

Hood.

|

|

|

The

legend of Robin Hood explored for its Yorkshire roots, and the Farndale

connection with the legends, first as the class of poachers who gave rise to

the inspiration, and later their fifteenth century descendants who lived in

the place where the stories emerged |

Whether you

perceive these folk as petty criminals or heroic merry men, you will

find plenty of such characters amongst our medieval forebears and in the early

history of the folk of Farndale.

We might

have some sympathy for our forbears. There were large

numbers of landless folk exacerbated by the Great Famine following bad weather

and poor harvests in 1315 which gave rise to widespread unrest, crime and

infanticide. The Black Death hit

Yorkshire in March 1349. The Normans had deprived our ancestors of their

traditional forest hunting grounds by which their own forebears had survived by

finding meat and subsidence, when they reserved vast areas of Pickering stretching into Farndale, as royal forest.

It happens

that descendants of the Farndale outlaws, came to live at Campsall in

Barnsdale Forest two centuries later, in the place and at the time when the

ballads and tales of Robin Hood started to be formally recorded and written

down. So on a separate page we explore the association of the thirteenth and

fourteenth century poachers, with the fifteenth and sixteenth century

storytellers of the legends of Robin

Hood.

Poachers

turned game keepers

Victorian

Britain was a place of contradiction. On the one hand there was a cultural

emphasis on politeness and cultural achievement. On the other hand, there was

ruthless treatment of criminals and the poor. In rural areas, there was harsh

punishment of poaching, which was probably still at that time a continued sign

of rural inequality in times of enclosure, which deprived the poor of common

land for pasture and fuel.

By then

however more innocuous signs of desperation were mixed with organised crime,

particularly in urban areas. More widely there were violent armed gangs,

involved in smuggling, poaching and housebreaking. Dick Turpin, later

romanticised, began his criminal career as a gang member in Essex. Most crime

however was petty. There were few prisons or police at the start of the

nineteenth century. Victims generally had to take matters into their own hands.

Local power depended on deference, but by the early eighteenth century,

deference had to be earned. There was a growing confederacy between those

working on the land who increasingly saw the Squire’s property as fair booty

and who colluded to help each other against punishment. Attempts to enforce

ancient Game Laws which reserved all game to the lord of the manor, led to

serious confrontation.

Descendants

of the medieval Farndale family were both associates of the smugglers and enforcers of the law. As

farmers in their own right, they often came to encounter their own

problems with poachers and had little option but to vigorously pursue

poachers, trespassers and damage causers. From the 1870s we find extensive

records of Martin

Farndale being involved in criminal proceedings against poachers,

trespassers and damage causers on his land. Since this was a time of

depression, we might have sympathy with those who were acting out of

desperation and remember Martin’s ancestors, who had been fined, outlawed and

excommunicated, around Pickering Forest, for poaching in the King’s forest. On

the other hand, we must recognise the difficulty for farmers in protecting

their livelihood. Martin had to rely on the criminal courts to protect his

livelihood.

Medieval

poaching was certainly a sign of the desperation encountered by many of our

forebears. As time went on, the issues behind poaching became far more

complicated, but it continued as a component of the historical story, into

modern times.

or

Go Straight to Act 8 - Pathfinders

Before you

do that you might like:

· To Explore Pickering Church, with its

medieval mural depicting archers amongst other things, visit Pickering Castle, where our

ancestors were put on trial, and perhaps drive through the Yorkshire

Forest, in the lands of the once vast Pickering Forest where these

offences took place.

· To meet some of the poachers

themselves including Richard

and Thomas Farndale, Roger Milne

of Farndale, Robert

de Farndale, William

Smyth of Farndale and John Farndale.

If you’d

like to read some more about poaching in Pickering Forest, there are many

articles including

· The

Poachers of Pickering Forest 1282—1338, Derek Rivard, Medieval Prosopography, Vol.

17, No. 2, Autumn 1996, pp. 97-144.

· An article about Medieval Forests in

North East Yorkshire written in 1988 in the Ryedale Historian.

· The Honor

and Forest of Pickering, edited and translated by Robert B. Turton, 4

vols., North

Riding Record Society, n.s.,1-4 (1894-97), 2: 60-62.

· Elizabeth C. Wright, Common

Law in the Thirteenth Century English Royal Forests [Philadelphia,

1928]).

· Charles R. Young, The

Royal Forests of Medieval England (Philadelphia, 1979)

· Raymond Grant, The

Royal Forests of England (Wolfeboro Falls, 1991).

· Jean Birrell, Forest Law and the

Peasantry in the Thirteenth Century, Thirteenth Century England II:

Proceeding of the Newcastle upon Tyne Conference 1987 , ed. Peter R. Coss and

Simon D. Lloyd (Woodbridge, Suff., 1988), pp. 149-64.

· Who Poached the King's Deer? A Study

in Thirteenth Century Crime, Midland History [1982]: 9-25.

· Hunters and Poachers: A Social and

Cultural History of Unlawful Hunting in England 1485-1640, Roger B. Manning, August 1993.

· Forest Laws from Anglo-Saxon England

to the Early Thirteenth Century, chapter 19 of The Oxford History of the Laws of England:

871-1216, John Hudson.

· The

Extent of the English Forest in the Thirteenth Century, Margaret Ley Bazeley,

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 4 (1921), pp. 140-172.

· The

Forest Eyre in England during the Thirteenth Century, Charles Young, The American Journal

of English History Vol 18 No 4, October 1974

The

underlying historical research is at the Poachers of

Pickering, with chronological records and references to source material.